Introduction

Doing more with less is a frequently echoed healthcare mandate that demands strong creative contributions from each team member. Although everyone on your team is probably creative, methods to stimulate creativity and a progression of creative management techniques help maximize this essential resource. To be progressive and to achieve its goals and objectives, a healthcare organization must tap the creativity of all workers throughout its ranks but unfortunately, in many healthcare environments, creative ability goes untapped. For example, some organizations are highly structured and do not encourage or reward creativity. Other organizations encourage creativity but do not progressively reward creative contribution. For a healthcare organization to survive and thrive, it is essential that all members attempt to make creative contributions that generate positive results and further the organization’s goal of high-quality and affordable patient care.

As a newly appointed healthcare manager, you have a prime opportunity to foster a creative environment within your department and to set precedent with the plans you implement and the policies you incorporate into your management approach. Creativity not only helps in organizational achievement, it also acts as a positive catalyst within a department, as it improves morale and fosters a sense of participatory allegiance.

The opportunity to be creative inspires participation from all members of the staff and demonstrates to them that what they bring to the effort is valued and vital to the organization’s success. Creativity is essential to the growth and development of all members of the organization. To grow and develop on the job, your staff must stretch its wings and venture into new areas and explore new methods of achieving results. As mentioned, creativity is a primary healthcare mandate. With customer/patient placing new demands on providers and needing services that heretofore were either nonexistent or unavailable, it is critical for each member of the healthcare organization to offer ideas that might meet these consumer demands.

This chapter will explore the prerequisites for creating an environment, examine the fundamentals required to encourage creativity throughout your department, and, most importantly, provide you with specific strategies for boosting creativity and garnering new ideas and approaches from your staff. These objectives will be accomplished with a view toward how you as a new manager can apply these strategies to your own personal development while using them to institute new programs. After reviewing these strategies, you will be able to build a creative environment in which to exercise your own management responsibilities.

Establishing a Creative Work Environment

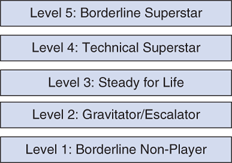

To develop a creative team process, the work environment must be conducive to breeding new ideas and new approaches on the part of workers. Furthermore, your team members must know that their creative thought will be valued and rewarded, so that they do not feel afraid or intimidated to present creative solutions. This of course, is easier said than done, for reasons that will come to light in the following section and subsections. As this chapter progresses, you will be presented with group and individual strategies that will help facilitate the creative process.

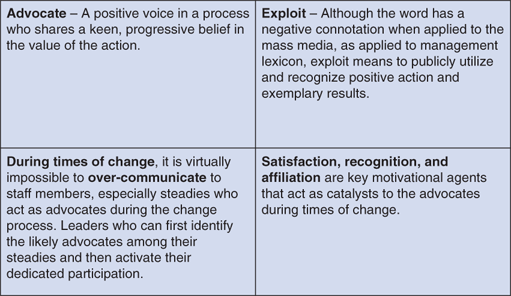

The team creative process begins with identifying individuals among your superstar and steady employees that will be helpful in establishing the proper climate for creativity. With this objective in mind, review the following specific list of your more positive, likely creative contributors:

The true superstar

The new team member

The previously disenchanted individual

The technical expert (or techie)

The untapped steady

Once again, although running the risk of stereotyping, you are simply categorizing personality types who will help you establish a creative environment. These are the likely depositors into your creative idea bank, and they strongly and fully support your efforts. Many of these individuals have been hungry for the chance to provide creative input, and your new presence represents for them an opportunity to liberate their ideas. These individuals will be like a strong thoroughbred who merely must be guided and directed toward the finish line as you run for the roses.

True superstars are the positive leaders in your department who possess most of the technical knowledge and consistently demonstrate stellar professional ability. Their very presence and approach to the daily undertaking of their work responsibilities indicate that superstars are employees who would run through the wall for the organization. They will become your demonstrable role models for the work group and will always be ready and willing to present new, creative input that will lead to positive action.

Draw on these individuals heavily in the creative process. Ask for their opinions and input first in your work discussions and have them summarize their objectives and intentions at the end of the meeting. This will also underscore the type of performer you value on your staff. Furthermore, make certain that you clue these people in, without playing favorites, prior to any creative meetings. For example, upon a chance encounter with a superstar the day before a creative input meeting, give him or her some specific objectives to think about and ask that he or she be ready to share input at the upcoming meeting. Superstars provide a stellar contribution to your staff and hence deserve the reward of special consideration. Again without showing favoritism, show respect for their ideas and give them the maximum opportunity to contribute—which they richly deserve.

The new staff member can also be prime contribution to the creative process. For example, new members recently arrived from other institutions may have a wealth of ideas on new applications for their work activities. They also may have several ideas of what worked or did not work at their previous institution. Hence, they might have some new angles that can benefit your staff and help spark forward thinking in your creative meetings. You also might have new department members from other parts of the organization. They also will have new ideas and approaches and a sense for what did or did not work in their previous department.

Once again, tap these sources for their creative input. Their immediate participation will help make them part of the team right away, and they and the veteran team members will get to know one another at once. Hopefully, they will get off on the right foot in establishing their work role within the department and will be positively drawn to your other strong players.

A less obvious but likely creative contributor is the previously disenchanted individual. In many cases, new managers take on responsibility for a department that is in trouble. Put frankly, you may have gotten your job because your predecessor had a large hand in the department’s poor track record. In many scenarios, new healthcare managers are replacements for predecessors who were totally ineffective, too authoritarian, or simply were not sound communicators. Individuals who worked under such leadership may have been strong performers but became disenchanted and disengaged from the staff performance process. They fundamentally did their own thing, without regard to departmental progress or team contribution. They likely were strong performers and well-motivated individuals prior to your predecessor’s arrival.

Once again, you have a prime opportunity to use the creative process to achieve overall greater staff performance. By allowing these disenchanted players the opportunity to contribute and provide their input, you are recognizing their abilities and demonstrating clearly your esteem for their performance. In many cases, they will respond by returning to their previous high-level motivation. Remember to also examine the dynamics of their job descriptions and daily work responsibilities. One technique in this regard is to spend a day with each individual in your department at the outset of your management tenure. Constantly ask questions to learn as much as possible not only about the work role but also about the individual. This establishes an excellent precedent for dialogue and allows you to spur their creative and innovative thinking right from the outset.

Workers with a negative attitude for any number of other legitimate reasons might also fall into the category of the disenchanted. For example, their job may have been restructured for good reasons; the lines of report may have changed; or they may be suffering inordinate stress created by workplace circumstances that may now be smoothing out. In each case once you have identified the person as disenchanted, delve not so much into the circumstances of what created their outlook, but apply your efforts toward positive action.

For an individual who has a negative attitude, identify what created the negative attitude. If it is something that is job related, consider restructuring or reorienting the job role and the basic job description. If it is something that does not pertain to work but rather is generated by the individual’s personal life, you might want to get an assist from your personnel department or an employee assistance program. If the negative attitude was specifically pertinent to the actions of your predecessor, simply ask this individual for a chance to prove yourself as a manager, thereby enlisting his or her support and participation. If the individual fails to respond to any of these actions, you no longer have a potentially supportive team member—you have a nonplayer performance problem.

As discussed throughout this book, most of your staff are technically proficient or techies. For these individuals, their work interest is founded in the technical application of their jobs. They have a strident affection for these technical angles, even though they sometimes may appear to live in their own little world. This work is defined by the parameters of their technical aptitude and the responsibilities that specifically utilize their technical expertise. A strong healthcare manger plays to the strengths of these individuals while ensuring that they continually have opportunities to participate fully in the work of the team.

(Figures 8–1 and 8–2)

Additionally, techies can also fall into the category of the untapped steady, an individual who endeavors to put in a good day’s work for a fair day’s wage but could be enticed to give a little more if approached appropriately. Like techies, untapped steadies are interested in the organization, but heretofore have never been specifically challenged to make creative contributions. Involve them in the group process, specifically charge them with idea innovation directives, and, regardless of category, make the process as engaging and enjoyable as possible.

Stimulating Innovation Input

It is essential to use some techniques immediately upon entering the management ranks to establish a creative environment. This section will discuss several techniques you can incorporate into your style to make the creative process part of your everyday positive work actions.

To begin with, remember to play to individual strengths. That is, encourage an individual who has a strong technical proficiency to come up with technical ideas and newer specialty innovations that might bear on the entire department. Widen your scope as you do this; for example, ask a radiology technician how he or she might improve laboratory performance outcomes utilizing existing resources and providing stronger service. Then, using that person’s own activities as a base, ask what might be done to encourage stronger intradepartmental cohesion—that is, how others in the department can better support this efforts of other in the department.

This process can be started, as mentioned, by utilizing a spend-a-day-with program. Upon assuming your management responsibilities, try to spend a day with each individual on your staff. Try to learn the specific objectives of each department member and the specific dimensions of his or her work role. This activity will also help you in the creative process, as you will get ideas on potentially reorganizing the department, restructuring certain jobs, and utilizing all the resources in your department more fully.

In undertaking this endeavor, present each individual with a brainstorming notebook. Ask each to record any ideas that answer the following questions:

What can I do to make a stronger contribution?

What resources would I ideally like to have to get my job done?

What new and different approaches have I heard about or read about relative to my technical area?

What new and different approaches have I heard about that might assist us in becoming a better department or better organization?

What wild and crazy ideas have I considered and think they might actually work and generate positive results?

With this notebook approach, you are formalizing the creative process. Each individual will see clearly that idea generation will not be your exclusive domain but a team effort in which everyone’s participation is encouraged and valued. To follow up on this technique, try to hold meetings at least monthly, but certainly quarterly to review all new ideas generated and allow everyone the opportunity to offer their ideas and present any suggestions that might bring about positive action.

As discussed repeatedly throughout this book, it is vital to ask questions throughout the creative process. Numerous questions have been provided throughout the text that you can use in a variety of management situations. Always ask questions on both an individual and a group basis. This not only allows you to get answers that are pertinent and valuable to your own management activity, it also encourages all members of your staff to ask questions. As posed by a popular media advertising campaign several years ago, great companies always ask “What if…?”—in a similar vein, the biggest question you can ask in the creativity process is “What would happen if…?” Always present ideas, and try to get the up side and down side of incorporating any new ideas or new programs into your daily activities. After all, if you do not ask the question, you will never get the answer, and you might be missing something that could be valuable to your departmental activities.

Many organizations take asking questions a step further by holding what are commonly called blue-sky meetings. In blue-sky meetings, individuals are charged with looking at the short-term and long-term perspectives of their department, and while considering their department’s future, they are asked to ascertain specifically what mission and objectives the department should be pursuing. In following this strategy, they try to innovate plans that accommodate these new suggestions. If you use innovation notebooks and give each individual in your department an idea notebook, you have a ready-made resource to use in these meetings. You can supplement this effort by simply asking, “If you had a magic wand, what would you make it do—besides making the hospital disappear or crating a perfect world?” This is yet another way of generating new ideas and allowing people to expand thinking in a free-flowing manner.

Encourage individuals to consider all sources in their idea generation. This would extend not only to other departments within your organization but to any ideas that they might have heard or read about in the media. It can also include ideas from organizations that they are involved with, aside from their healthcare employer. For example, they might belong to a community, civic, or religious organization that utilized a successful management or customer satisfaction system.

Most times, customers/patients are also neighbors of the organization’s employees. Therefore, individuals in your department probably have access to a vast repository of ideas on how to improve service and, certainly, on common perceptions of the institution held in the community. Some of your staff members might have heard comments about your healthcare facility and specifically about your department as compared with other provider organizations and departments. This can also be a tremendous source of ideas and potential new applications. Finally, their previous job experience and the input they hear from peers within the organization might be yet another untapped resource in idea generation, which can be collected in their idea notebooks and presented in your meetings.

Most of the individuals in your department attend some sort of education and development programs. They could be programs presented by a technical organization, a civic organization, or in-service education within your institution. In all of these activities, your staff hears the perceptions and ideas of other individuals. Once again, they should bring significant input back to your idea generation meetings and record in their idea books specific comments that might be helpful. For example, a dietitian might attend a national association meeting and come back with ideas on a food program used by a hospital in another state.

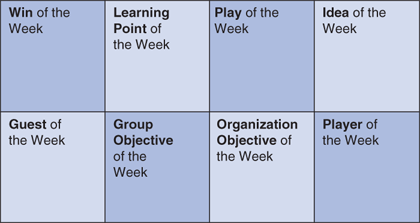

Individuals attend retreats and workshops that might have very little to do with their technical areas, as these functions engender their participation by virtue of their membership in community organizations. Once again, some useful ideas could be generated. Furthermore, in some healthcare organizations, managers go on retreats to discuss basic issues and receive the benefits of professional education. This is yet another source for new creative ideas, as are weekly meetings when conducted as illustrated in Figure 8–3.

Regardless of what idea sources are used, it is incumbent upon you as a manager to identify the value of acknowledging and recording potentially useful ideas. No idea is a poor one—it is simply that some ideas have more merit and potential application to the workplace than others. Therefore, it is important to identify the importance of considering all sources in idea generation, to encourage all members of your staff to present these ideas, and to reward individuals who contribute new ideas through recognition and other merit systems.

To provide you with an even more concrete framework for bringing imagination and ingenuity into your workplace, this section presents the I-formula, which was devised by the authors for use by military officers in the late 1970s and has since been adapted and utilized successfully by thousands of healthcare managers. It is a simple approach to inspiring innovation in the workplace and making imagination and creativity an everyday part of the healthcare workplace. This section will review all elements of the I-formula, explain the importance of each element, and utilize case study examples of a healthcare manager’s application of the formula in dispatching his or her own responsibilities, as well as a case analysis of healthcare manager who used the formula for his or her staff.

The formula is structured in four phases: need, design, action, and establishment. Each phase is further divided into six subphases, for a total of 24 I-components.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree