Education and Development

You can reap great returns from healthcare training and development efforts. It is often said that management is an art, very qualitative in scope, and greatly reliant on style. Others maintain that management is a science, technical and quantitative in scope and reliant on research and acquired expertise. Others maintain that management is a set of skills, which could be acquired through formal knowledge and then incorporated by individuals into their everyday activities. Still others maintain that management rests on pure magic, reliant on luck, gut feel, and basic instincts and is greatly dependent on the will of the managers to do the right thing, which in turn will provide its own rewards.

You have probably quickly realized that management and leadership are actually a combination of all of these dimensions, a true confluence of art, science, a set of skills, and magic, with the only constant being that you can never learn too many useful strategies. Training and development, when specifically applied to managers as a management development effort, can assist you in attaining competency in several basic areas. More to the point, it can help you in terms of developing your own abilities, with each experience providing an enriching and encouraging lesson in dealing with people and making yourself a better professional.

The Learning Curve

As Figure 9–1 indicates, you are currently on a management learning curve; over time, you will achieve a certain degree of competency. If you consider the figure and its charting of a manager’s typical first year, it demonstrates how competency will increase each quarter as you acquire the skills charted in the graph.

Initially, you should try to master observation skills. Closely monitor the progress and performance of your staff, observe the actions of your peers, and study closely the styles and applications of the managers and leaders with whom you work. To the extent possible, listen to all experiences in all areas of expertise, and try to perceive each episode as a lesson. This will provide you with a basic frame of reference in management, as well as with some specific information needed to lead and mange the individuals on your staff. Observation will also help meld your relationships with peers and superiors.

The second phase of management is the trial and error. Typically this occurs in the second quarter, although certainly no time lines are considered absolute in every case. In the trial-and-error phase, try to establish some policy, make decisions, and operate as an agent of change within your sphere of responsibility. As you continue your education in this school of “burn and learn,” few things will work perfectly the first time, but you learn from your mistakes, get better all the time, and acquire some expertise. The third phase, participative learning, takes into account the entire range of activities you will learn and grow from and apply practically to your business situation. At this point, you are probably acting as an instructor yourself in delivering information and providing instruction to your staff. Additionally, you are providing expertise to your peers and consultation to others who need your assistance. If you are keeping a logbook (which is highly recommended) and applying many of the techniques discussed throughout this book, this phase could be a very successful period, one that provides you with some much-needed positive reinforcement.

Mastery of the participative learning phase leads naturally to assuming a leadership role, the fourth phase of the curve. As a leader, you are on your own and have acquired a certain degree of competency—although you are still learning, which, hopefully, you will never stop doing. The worst risk you could incur is failure to stay current with new management techniques, innovative ways of dealing with people, and advancements that sharpen your technical acumen.

Sources of Learning

As a new healthcare manager, you will receive information and education from a variety of sources. These sources include, but are not limited to, the following:

Peer input: The perspective provided by peers as well as their common experience in becoming healthcare managers can prove invaluable. Remember, all situations are not identical, and the circumstances under which they worked in their initial management phase might differ from yours. However, generally this could be a good source, as these individuals have walked in your shoes.

Personal experience: You own personal experience in health care which will be a valuable asset as you enter management. This experience is a source of information because you have acquired a certain degree of expertise and have certainly observed healthcare managers in action. Rely on your gut instincts as well as your own knowledge in terms of what does and does not work. Use this reference throughout your management career.

Related experience of others: The managerial experiences related by others in your organization (or by family or friends) can be very helpful. Although the banking industry, for example, certainly differs from health care, certain aspects of people management share similarities. Once again, examine these experiences, ask questions, and try to gain knowledge from this important source.

Organization-generated education: Seminars, workshops, and other educational opportunities provided by an organization can be invaluable in establishing a reference point as a healthcare manager. Take advantage of any and all educational opportunities the organization provides, specifically those on management of healthcare business issues.

Journals and other reading: A whole body of healthcare management literature is available for your perusal and use. Try to select reading material that is practical in scope and provides information you can apply immediately. Ask peers and others in your organization whose opinions you respect, which periodicals they subscribe to and find most valuable. Most publications of the American College of Physician Executives and other professional leadership development organizations tend to be very practical in scope and provide valuable information that can be used immediately by newer and seasoned managers.

Formal education: Although many healthcare managers endeavor to attain a management degree, perhaps at the graduate level, it could be equally valuable simply to take a course that relates to a specific development need help in financial skills; certainly, your local community college or state university has a course on finance for the nonfinancial manager that can meet this development need. Do not feel compelled to acquire a new degree—simply pick the courses and seminars that are most applicable to your situation and will provide the most immediate feedback and value.

Project management: As always, keep a journal or logbook in which you will record any major projects you undertake or significant issues you must manage. Keep a chronological log of time and events, with an additional line displaying what you learned in each situation. This will provide you with your own textbook of management and give you a sterling reference for the next time you undertake a similar project or scope of responsibility.

Supervisors and mentors: Your supervisor can be a valuable source of information and a terrific educator if you are comfortable with the relationship and feel he or she has a certain amount of knowledge to offer. Furthermore, as will be discussed later in this chapter, the mentoring process is quite useful and has been adopted by many leading hospitals from an organizational perspective. Later in this chapter, appropriate individual strategies for mentoring will be delineated.

Staff input: The healthcare manager who discounts employees’ ideas and input as being invaluable or unnecessary is doomed to failure. Although there are few absolutes in management, this certainly is one of them. Try to learn as much as possible from employee comments, viewpoints, and by simply observing them in their daily activities. If nothing else, you will learn how they are motivated, what they respond to, and what they deem as being negative within the workplace.

Outside networking: As mentioned in the preceding chapter, as you progress through your career in healthcare management, you will establish a network of contacts throughout the business. Whenever you meet a potential contact, exchange business cards. Use a Rolodex or small file cabinet to store the cards categorized by state, business type, or title (pharmaceuticals manager, personnel coordinator). This can be a useful source of knowledge and a living library of healthcare management.

Types of Learning

To promote your development as a manager, there are basic ways of learning new skills that you should always try to make time for: communication-based learning, formal learning, and experienced-based learning.

Communication-based learning consists of simple observation, formatted observation, question-and-answer sessions, and secondary or hidden discovery. Simple observation is the act of perceiving as much as possible just by experiencing situations and either mentally noting or writing in a journal or logbook any significant incidents and learning points from the experience. This opportunity is always available to you and gives you a realistic perspective of how to deal with problems and reach positive solutions.

Another form of communication-based learning is formatted observation, that is, the undertaking of a project with a colleague or staff member at the outset of which you specifically delineated what you want to learn from the experience. By establishing this lesson plan, you can undertake the experience with your colleague and achieve specific learning objectives from meeting. Ask yourself beforehand: “What can I learn from this meeting?” At the conclusion of the meeting, simply answer that question, and determine what you did in fact learn from the meeting and what possible educational benefit it might have for you. Strive to achieve two or three learning points from each type of communication-based learning.

Two other types of communication-based training directly support the entire idea of quality-focused healthcare delivery. Question-and-answer sessions are activities in which you ask point-specific questions about important issues. These sessions could be prearranged with a group of colleagues, or held in a one-on-one setting with an individual with a creditable range of expertise. Secondary (or hidden) discovery is any experience in such a manner that you learned a great deal. For example, this might have occurred at a meeting in which you saw someone manage a communication conflict or a customer/patient complaint and detail how they brought about a successful resolution. Once again, you need a notebook to record these observations and the benefit of your hidden discovery. Hidden discovery can extend to leadership style, management aptitude, or basic supervisory psychology. Once again, it is readily apparent and available for your use.

Formal learning is at once the most obvious type of management education and, unfortunately, the least available. However, it is important and can delve into specific areas that might be of value to you in your role as a healthcare manager. Formal education can include reading and research, consisting of well-defined reading lists on management topics, such as the one contained in the bibliography at the end of this book or books recommended to you by your information and educational sources described earlier in this section.

Seminars and workshops are the second type of formal education. Be certain to attend those programs that are specific to your needs; avoid those that hint of trendy topics and very little meat. The way to determine this is to ask the instructor for a specific learning plan or simply discuss the content with the instructor using the material in this chapter’s Practical Resource.

The third type of formal education is perhaps the most obvious—formal coursework. This can include a college course of other type of educational offering that will provide you with specific information over a defined period of time.

Most newly appointed healthcare managers immediately feel a need to pursue outside education in the form of a degree program. This is a natural reaction, due to their innate feeling that entry into the world of management mandates more credentialing. Actually, your promotion was premised on your potential and established performance as a healthcare professional as perceived by those executives who provided you with the management opportunity.

However, if you insist on undertaking a degree program at the outset of your managerial career, keep certain cautions in mind. The first problem is that because your time will be limited, you could be setting yourself up for failure. For one thing, achieving a balance between personal life and professional responsibilities can be tough enough without the additional burden of keeping up with a new school regimen. Your effectiveness might drop as your stress level rises. Furthermore, the natural benefit of education—absorbing new ideas and enjoying the positive interchange with fellow students—may be compromised by efforts merely to make it to class and put in your time.

Some who enter healthcare management without BA or BS degree—perhaps an individual who was an RN or a practitioner and did not complete 128 hours most institutions require for a degree—become preoccupied with immediate acquisition of a degree and may feel professionally insecure without it. Although finishing your degree work is important, it is secondary in your first year, which must be spent learning as much as you can about your staff, the supervisory process, and a myriad of techniques essential to becoming an effective healthcare manager. Once again, time is the most precious resource you’ll need to manage during this period. Thus, the unnecessary intrusion of schoolwork into the equation will likely hurt your progress more than it will enhance it.

After your first year, it might be prudent to begin pursuing a new degree or competing outstanding coursework. As you consider your educational plans, the following guidelines might be helpful:

Pursue relevant courses. Whether you are considering a master’s program or completion of undergraduate work, focus on courses directly related to your current responsibilities. This will give you maximum immediate return on your efforts while providing insight and instruction that can be applied at once to your workplace.

Avoid becoming a slave to the degree process. Attaining a new degree is a laudable accomplishment. It also takes an inordinate amount of time and energy, particularly if the program is a traditional curriculum, which does not include weekend sessions or other more user-friendly opportunities, such as executive degree programs or night school. After reviewing course content, select programs that are most relevant to your job and development goals, not those that cater to instruction that can be applied at once to your workplace.

Seek out professionally oriented programs. Most progressive university programs are designed with the busy professional in mind. Such programs include weekend classes, credit for significant professional accomplishment already achieved, and faculty members who are in touch with the real world. This should be a major consideration in your decision-making process for the benefits are exposure to fellow professionals and a realistic and practical educational base.

Use moderation. At the outset of your new college work, take one or two courses that hold a specific value for your pursuits. This value may be defined, for example, by a course whose content may contain specific material relevant to your responsibilities or provide you with two or three immediately useful ideas for your management efforts. Either way, it may prove enjoyable to you. This approach—simply taking three or four courses that interest you and yield specific instruction in a key area, such as a graduate certificate program—may be more valuable than relentlessly completing an entire program and then wondering, “What did I get from that?” Remember, your time is limited, and your main qualifications for the current job and future opportunities are your past achievements and realistic potential. Additional degrees are secondary qualifications and are only valuable if directly contributory to attaining new knowledge and expanding your managerial perspective.

Self-directed instruction, including computer-assisted instruction (CAI), is another type of formal education. With the computer age in full swing, self-directed educational packages are very user-friendly and available from many fine education organizations. Check with your human resource department or, if yours is a larger facility, your educational department for suggestions on good self-directed packages.

Finally, the fifth type of formal learning is organization-sponsored programming seminars and other programs sponsored by your organization and provided for all its healthcare managers and staff. It is a good idea to attend as many of these programs as possible; you can learn as much from the dialogue among your fellow participants as you can from the instructor. Listen carefully to all questions, and engage in conversation with your colleagues following the program to get their perceptions and ways in which they might apply the material practically.

The third means of management development is that of experience-based learning. Experiential learning is the result of learning on the job. Suggestions for experienced-based learning include being attuned to the lessons of trial and error, being open to the benefits of mentoring, and practicing what you’ve learned—all the while keeping notes on what has worked and what has not.

The first experienced-based application is that of trial and error. As discussed previously in this chapter, this is simply the experience of your practical application of knowledge and learning how successful it might be. Remember to use the I-formula from the previous chapter in trying new ideas, reinvestigate what went wrong and what went right about your previous experience, and fine-tune your efforts accordingly.

Mentoring is yet another experience-based application, which is defined as one individual acting as a primary source of instruction for another individual. Mentoring can take place on a short-term basis, perhaps with a specific project or particular area of expertise or it can be a continuous process, such as the first year of a manager’s initiation into a supervisory position. Adherence to the mentoring guidelines presented later in this chapter can be most helpful.

Other experience-based educational process includes practical application of the knowledge you’ve gained in a realistic setting. Once again, use of your ever-present notebook is important, so that you can record many new processes you have now tried and mastered and notate what was learned from each experience.

Experience-based learning also includes your participation in the activities of a team, of which you are a part but not necessarily the leader. Collate information on what the team has achieved, what it has learned, and what you would do if you were the team leader. This will allow you to focus on the objectives and processes you will need as a team leader.

Two additional sources of experience-based learning are primary exposure and secondary-effect education. Primary exposure is the culmination of basic experiences you participated in and were a major agent for taking action. Secondary-effect education is the process by which you have learned from the triumphs and mistakes of others and have notated these accordingly.

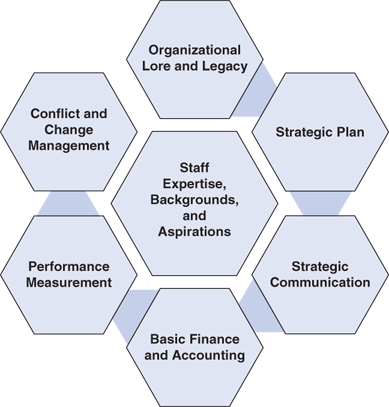

Numerous areas of expertise should be available to you within your organization for your own management development. Figure 9–2 identifies areas that are particularly important as you make the transition into healthcare management. Methods of acquiring these specific attributes and competencies are suggested through this book’s practical resources. Use Figure 9–2 not only as a review of the material in this section, but also as your own individual development plan as you experience what might be the most educational year of your life—your first year as a healthcare manager. The individual development plan will be discussed in further detail in the following section.

Staff and Employee Development

Of equal importance to your own development as a manager is the development of the staff and employees who report directly to you. As stated earlier in this chapter, training is essential to staff morale, individual motivation, and maximization of employee potential. As a manager, you are responsible for the training and development of all your assigned subordinates. Because of a dearth of training and development activities due to budget cuts and other factors, it is incumbent on you to provide staff training and development.

Many benefits can be derived from your acting as the major proponent of training and development for your staff. By instructing or facilitating a seminar or teaching an in-service program, you can increase your own presentation skills and public speaking skills. Although many people fear public speaking, it is essential to your own management development to achieve a certain comfort level in this area. By acting as a trainer for your assigned staff, you can achieve this objective.

Training provides other benefits to the manager. The more your staff is trained, the greater their level of competence and the higher their achievement level in all performance activities. A major objective of any department is to develop bench strength, a term that relates to the ability to have depth of talent across your entire department. Each strength is achieved by having a diversity of talent and individual strengths. Obviously, this can be enhanced by training and development throughout your group.

One of the most important things a manager must do initially in his or her new role is to establish credibility. Given that you have a certain degree of technical aptitude, as well as basic communication skills, you have a tremendous base from which to develop initial credibility. By training your staff members on a group, individual, or cross-training basis, you are demonstrating your knowledge as well as your dedication to their development. When you conduct group training, you help enhance team building. When you work with individuals on a one-on-one basis, you set a strong norm that shows your willingness to accept their ideas, your interest in their development, and your readiness to establish a work relationship based on communication and trust. When you cross-train your staff, you emphasize work role flexibility.

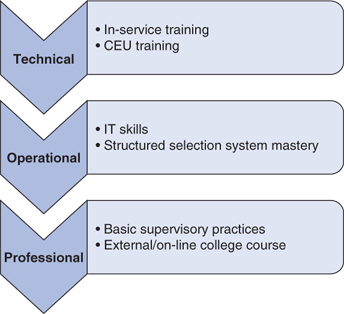

The individual development plan (IDP) is a sound tool for establishing a group training program (see sample in Figure 9–3). The plan identifies specific training needs for each staff member, as well as activities that address each need.

Start this process by, first noting the individual’s name, his or her current position and starting date, the date on which the IDP is being completed, and your own name as supervisor/manager. Next, write down specific training needs identified for each individual in the department, followed by the activity that should be undertaken to fulfill the training need, the estimated time the training should take place, the learning value of each training activity, and any comments related to the activity. This is a relatively straightforward tool and should be completed every year with a maximum of five objectives filled in for each individual.

Several procedures should be followed to ensure efficacy of the IDP. A logical starting point for establishing a training and development strategy is to perform a needs analysis. A needs analysis explores the strengths and weaknesses of all individuals within your department and projects a training plan on both an individual and a group basis. The exploration involves a comparison of individual strengths and weaknesses with basic areas in which you expect each team member to have a certain degree of proficiency. For example, areas of competency would include the basic nursing skills required of a floor nurse, the ability on the part of the pharmacist to fill prescriptions accurately, the ability of a recruiter to interview and select individuals, and so on.

Once the basic areas of competency have been identified, you will then conduct a basic inventory of the present skills of your team members and ascertain what direction their training should fellow. To do this inventory, first review the prior performance records of each employee, including any training records that might be on file, as well as the performance evaluation and appraisals from prior years. If possible, discuss with your predecessor each individual’s strengths and weaknesses, and take notes. Then assess your observation of each individual’s strengths and weaknesses in comparison to the information provided.

The second step is to sit with each individual and have a candid conversation of his or her strengths and weaknesses. The best way to conduct this conversation is not to use the words’ strengths and weaknesses but basically ask each employee “What type of training are you interested in?” Probe further by asking what areas he or she would like to improve in, what technical abilities to enhance, and what new areas are of interest. The net effect of this conversation should have enough data to complete the IDP effectively.

When using the IDP form, try to establish training goals and activities jointly. Ask for suggestions for what type of training might be undertaken, and what types of programs might be good for candidates. Always remember to use your human resource and educational departments whenever possible; they are experts in identifying training areas and usually have good data on what programs are effective and easily applicable.

A very important entry on the IDP form is that of estimated time of completion. Assigning a training goal is one thing—accomplishing the training needed is another. Make sure that you put a time range of 1 to 2 months (eg, March-April 2014) so that the individual can realistically address the training need on a timely basis.

Also discuss with each staff member the outcome of all training endeavors. Following their attendance at a training program, sit with each staff member and ask the following questions:

What were three major things that you learned?

Would you recommend the program to others?

On a scale of 1 to 5, how would you rate the learning value of the program (1 being highest value)?

What things did you learn that each of us here in the department can learn from?

By asking these questions, and perhaps using an evaluation form covering the program quality, you can build a data bank not only on the individual’s proficiency but on the strength of the training program. This will help you in assigning training goals for other individuals and give you a natural follow-up strategy with the individual’s development program.

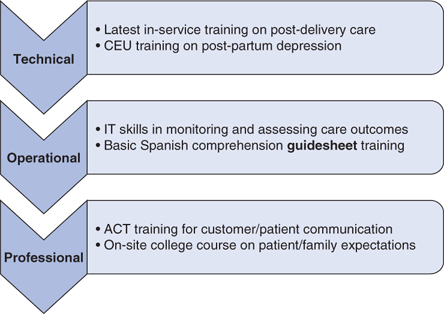

As you undertake the training and development process, specifically the needs analysis and other IDP functions, you will find that many individuals have similar needs throughout your department. Therefore, use a group IDP form as depicted in Figure 9–4. Simply enter the names of individuals who have common training needs, the event, the time, and the follow-up strategy you will undertake to ensure learning value. This might include a group discussion with the individuals who took the program or a series of one-on-one conversations to determine independently the quality of the program. Coordinating training needs in an economical use of time and money gives you a synergistic effect, as the individuals attending the same or similar programs will learn from each other as well as from the program leaders.

In establishing IDPs, make sure that you look to programs that are practical and will address specific needs. Do not try to overload individuals with training—3 to 5 training activities per year is about right given today’s healthcare climate and workplace conditions. Remember that training activities do not necessarily have to be restricted to workshops. Many individuals in your department, specifically those on your staff, can learn from the same sources of learning presented earlier in this chapter. Remember, however, that just as each individual has a different personality, he or she also has a different aptitude for learning and is interested in different agendas. Therefore, do not expect individuals to learn the same material in the same way, with the result. There might be common perceptions about the quality of the program, but the net yield will always be different. Take the time to understand each individual’s particular training needs, as well as the effect and outcome of each learning experience.

Serving As an Educator

Many times in your career as a healthcare manager you will be asked to act as a trainer for a certain program. Furthermore, there will be many opportunities to present training and educational materials to your own staff. Therefore, it is important to have a basic understanding of the dynamics of training and to take a look at some parameters for success.

Good training is only as good as the preparation that goes into the program. A smart trainer analyzes the group from several perspectives. First, take a look at individual personalities; determine who your talkers are and who your listeners are. Then try to determine how motivated the group is toward the training. Individuals will be motivated to training depending on the topic. Get a realistic grip on what the level of motivation might be, and plan your strategy accordingly. If the topic is dry, you might want to prepare a couple of videos. If it is a topic that lends itself to discussion, you might want to prepare some pertinent questions so that you can lead a guided discussion about the topic.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree