Dyspepsia

Non-ulcer dyspepsia

One of the major limitations of medical practice in the management of dyspepsia is the inability to identify a mucosal lesion. To a large extent, this may actually reflect the limitations of current endoscopic technology or the macular acuity of either the endoscopist or his or her pathologist. As the discriminant index for the identification of lesions has decreased with the advent of more sophisticated technology, the group or individuals in which a diagnosis cannot be established has similarly decreased. Nevertheless, a conundrum is provided by a situation in which a patient complains vigorously of a group of symptoms that have been generically accepted by the physician as synonymous with dyspepsia if no lesion can be identified. In some circumstances, the skill of the practitioner and the attitude of the patient will allow for consideration of functional overlay. In other instances, the symptoms are not diagnostic of dyspepsia and, indeed, may wax and wane in severity as well as altering somewhat in nature as time passes.

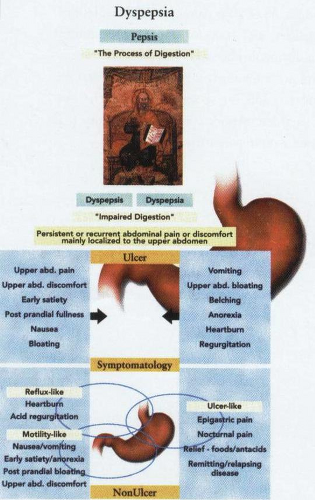

A depiction of the complex interplay between the different types of symptomatology broadly grouped together as dyspepsia. |

The critical difficulty in patients of this type relates to the actual definition and meaning of the word dyspepsia. Although this has been broadly defined as “pain or discomfort centered in the upper abdomen,” this definition does not include coexisting symptoms that may occur at other sites. To override the limitations that subjective descriptions of symptomatology proffered by a patient might generate, a more cohesive definition of functional dyspepsia may be used. In brief, this embraces the dyspepsia complex of symptoms using three broad categories: (a) ulcer-like dyspepsia, (b) dysmotility-like dyspepsia, and (c) unspecified (nonspecific) dyspepsia. In the ulcer-like dyspepsia group, a predominant complaint should be upper abdominal pain, usually located in the epigastrium, relieved by foods and antacids, and occurring before meals or when hungry. Occasionally, this pain may awaken the patient from sleep and be associated with a timing pattern characteristic of periodicity, with remissions and relapses. It is likely that this group actually contains patients who may have acid peptic disease but in whom no overt (macroscopic) ulceration can be detected by conventional technology. In many of these patients, relief will occur with the use of H2 receptor antagonists as well as PPIs.

In a second group—dysmotility-like dyspeptic patients—pain is not the dominant symptom, although upper abdominal discomfort is present. Usually, the discomfort is chronic and characterized by early satiety, post-prandial fullness, nausea, retching, and even vomiting. Although the patient may describe a bloating sensation in the upper abdomen, no visible distension is evident,

although it and all the above symptoms are usually aggravated by food. The symptomatology of this group of patients is not at all well understood and overall reflects the generally poor clinical understanding of motility disorders. Some of these patients, however, may not only represent abnormalities of gastric emptying but also disturbances of either gall bladder function or colonic motility.

although it and all the above symptoms are usually aggravated by food. The symptomatology of this group of patients is not at all well understood and overall reflects the generally poor clinical understanding of motility disorders. Some of these patients, however, may not only represent abnormalities of gastric emptying but also disturbances of either gall bladder function or colonic motility.

The last group of patients, who are categorized as exhibiting unspecified or nonspecific dyspepsia, is a heterogeneous group that may include individuals with definable neurosis and demonstrable functional disorders if evaluated by a psychiatrist. Part of this group, however, may fall into the poorly understood and heterogenous syndromic collocation of irritable bowel syndrome.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree