Drainage of Perirectal Abscesses, Surgery for Anal Fistulas, and Lateral Internal Sphincterotomy

Perirectal abscesses begin as infections in the anal glands, which empty into the anal crypts. From the anal crypt, infection spreads laterally into the soft tissues of the ischiorectal fossa. The abscess commonly presents as a painful swelling visible in the external aspect of the buttock. Occasionally, infection will track above the levator sling, causing pain and a mass that is palpable on rectal examination. Drainage of a perirectal abscess often results in a chronic anal fistula, a communication from the inside of the anorectum to the skin of the outside. Perirectal abscesses and anal fistulas will be considered together because of their common pathogenesis.

A separate minor rectal operation—lateral internal sphincterotomy—is performed for chronic sphincter spasm associated with anal fissures. Pain from the fissure causes a vicious cycle of sphincter spasm, pain with defecation, trauma to the mucosa, and development of a chronic ulcer. Division of the internal sphincter breaks the cycle and allows the fissure to heal. In this chapter, the anatomy of the anal sphincter mechanism is presented through the operations for perirectal abscess and anal fistula as well as through the discussion of lateral internal sphincterotomy.

Steps in Procedure

Drainage of Perirectal Abscess

Lithotomy position

Digital rectal examination and palpation of lateral tissues

Incision on skin overlying abscess, close to anus

Digitally explore and break down loculations

Drain submucous abscesses into the rectum

Pack

Surgery for Anal Fistula

Lithotomy position or prone jackknife position

Identify external opening(s) of fistula

Cannulate and identify internal opening with blunt-tipped probe

Divide soft tissues over tract—avoid dividing the sphincter

Pack wound open

Lateral Internal Sphincterotomy

Lithotomy position

Make incision in intersphincteric groove, lateral aspect

Hook up fibers of internal sphincter and divide

Confirm complete division by palpation through anal wall

Curet base of fissure, if present

Close incision with single interrupted suture

Hallmark Anatomic Complications

Inadequate drainage with recurrence

Damage to sphincter

List of Structures

Anus

Anal canal

Dentate line (pectinate line)

Internal sphincter

External sphincter

Levator Ani Muscles

Pubococcygeus muscle

Puborectalis muscle

Iliococcygeus muscle

Coccygeus muscles

Gluteus maximus muscles

Superficial transverse perineal muscle

Obturator fascia

Hemorrhoidal venous plexus

Ischiorectal fossa

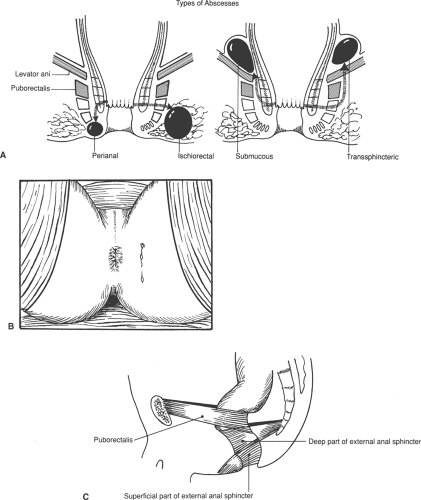

Drainage of a Perirectal Abscess (Fig. 100.1)

Technical Points

Abscesses and fistulas are commonly classified according to the path taken by the burrowing infection relative to the levator sling and the external anal sphincter (Fig. 100.1A). The most common type of abscess is the perianal abscess, which results from infection tracking down the intersphincteric plane to the perianal skin. These small, relatively superficial abscesses are very close to the anal verge and usually can be drained in the office; any resulting fistula will traverse part of the internal

sphincter and can be opened without fear of incontinence. When the infection tracks laterally across the internal and external sphincters into the ischiorectal fat, an ischiorectal abscess results. Less commonly, infection tracks cephalad, and pus accumulates above the levator sling.

sphincter and can be opened without fear of incontinence. When the infection tracks laterally across the internal and external sphincters into the ischiorectal fat, an ischiorectal abscess results. Less commonly, infection tracks cephalad, and pus accumulates above the levator sling.

Drainage of a perirectal abscess is generally performed with the patient in the lithotomy position. After administration of general anesthesia, a careful rectal examination is performed. Feel the tissues lateral to the rectum between your thumb (outside the anal canal) and forefinger (within the anal canal) to determine their thickness. Often, even though a mass is not palpable, a thickening in one area may be apparent on careful examination. Prep the area with povidone-iodine solution (Betadine). Perform a proctoscopy if you have not already done so as part of the initial evaluation. Make an incision through the skin over the abscess, as close as possible to the anal verge. (This will help to ensure that, if a fistula results, the tract will be short.) If you are unsure where the abscess is located, aspirate with an 18-gauge needle and syringe before drainage and confirm the presence of pus. Deepen the incision using a hemostat until the cavity of the abscess is encountered. Carefully insert a finger and break up all loculations to drain the entire cavity well (Fig. 100.1B). Irrigate the cavity and pack it with clean packing. If necessary, excise some of the skin edges to provide easier access to a deep cavity.

Submucous abscesses should then be drained into the rectum, rather than externally. To do this, place a retractor in the anal canal, dilating the anus to expose the abscess. Confirm its location by aspiration with a needle and syringe. Incise the mucosa overlying the abscess and allow it to drain into the rectum. If the cavity is large, place a Penrose drain in the abscess cavity to keep it open. Generally, such a drain will be passed within 1 to 2 days.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree