Professionals often must establish relationships with and elicit personal information from their clients. The latter may be uncomfortable for the client for at least two reasons. First, the professional is essentially a stranger to the client. Second, in some professions, such as accounting and law, clients must reveal sensitive information to the professional.

Doctors must also establish relationships with and elicit personal information from clients (i.e., patients). Only in medicine, however, must the practitioner also obtain information about the client’s most personal space— his or her own body. This task is made more difficult by the fact that medical practitioners often have to obtain this information under stressful, painful, or even life-threatening circumstances.

Establishing effective communication between doctor and patient is the first step in establishing the essential alliance that will allow the doctor to help the patient. This step is affected by many factors. For example, a patient’s earlier experiences with medical care can affect how he or she responds to the doctor. A doctor’s unconscious countertransference reactions based on past relationships can affect how he or she relates to the patient (see

Chapter 8). Other factors that affect the doctor-patient relationship include the patient’s physical and mental condition, personality style and coping mechanisms (see later text), use of defense mechanisms (see

Chapter 8), and cultural belief system (see

Chapter 18).

Establishing an effective interaction with a patient can take time, but it is well worth the effort. Increased patient satisfaction with the physician and adherence with medical advice, as well as decreased patient complaints and malpractice claims (see

Chapter 26) are closely related to the quality of the doctor-patient relationship (

Tamblyn et al., 2007).

• GETTING INFORMATION FROM PATIENTS

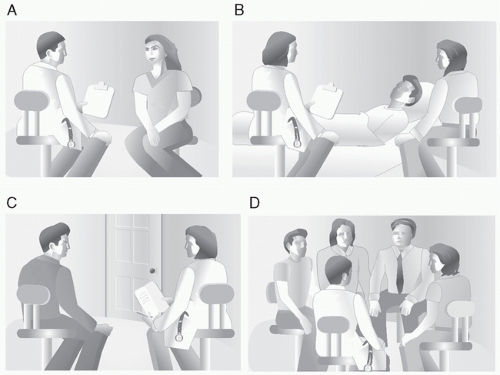

The clinical interview is the most important tool a physician has for obtaining information about a patient. An effective interview starts with establishing trust in and rapport with the patient. Doing this involves maximizing the physical placement of the doctor and patient to facilitate effective and safe interaction (e.g., staying at eye level with the patient and avoiding desks and tables) (

Fig. 24-1) and then gathering the physical, psychological, and social information needed to identify the patient’s problem.

The clinical interview

The clinical interview is used to obtain the patient’s medical and psychiatric history (see

Table 10-3) and to gather other relevant information. The two major categories of questions used in the clinical interview are open-ended

and direct.

Open-ended questions are unstructured, do not close off potential areas of pertinent information, and allow for a variety of responses. These questions are used in the interview to facilitate conversation and obtain information.

Direct questions are those that can be answered with “yes,” “no,” or a few simple words. They are used to clarify the information obtained from open-ended questions. For example, an open-ended question such as “Describe the pain” is used to get an overview of the patient’s distress. “Does the pain wake you at night?” is a direct question about a specific area of interest.

Direct questions are also used to elicit information quickly in an emergency or when a patient has a cognitive disorder (see

Chapter 18). This type of question may also be preferred when a patient is sexually provocative toward the doctor or overly talkative. Whatever the situation, doctors should avoid using

leading questions that suggest an answer, such as, “You really feel better, don’t you?”

Specific strategies and techniques, such as support, empathy, validation, facilitation, reflection, silence, confrontation, and recapitulation, that are used in interviewing patients are described in

Case 24-1.

Defense mechanisms in illness

People unconsciously use defense mechanisms to protect themselves from realities that cause conflict and anxiety (see

Chapter 8). The need for such protection is intensified by illness. Unfortunately, a patient’s use of defense mechanisms can act as a barrier to the physician in obtaining information and in gaining patient adherence.

Two of the most common defense mechanisms used by people when they are ill are denial and regression (see

Table 8-2). In

denial, a patient unconsciously refuses to admit to being ill or to acknowledge the severity of the illness. Use of this defense mechanism can be helpful initially because it can protect the individual from the physical and

emotional consequences of intense fear. However, denial can be destructive in the long term if it hinders the patient from seeking treatment. For example, if a patient in the initial stages of a myocardial infarction attributes his severe chest pain to a minor problem like indigestion, his physiological fear responses (e.g., increased heart rate and blood pressure) will be attenuated. However, if the patient persists in this denial and fails to seek treatment, he increases his risk of dying.

In regression, the ill patient reverts to a more childlike pattern of behavior that may involve a desire for more attention and time from the physician. This response can make it more difficult for the physician to interact with and treat the patient effectively.

Interviewing children and adolescents

Like adults, children and adolescents respond best during a clinical interview when they feel comfortable with the doctor. In contrast, the type of

questions most effective in interviews with adults may not be appropriate for children. For example, young children may have difficulty responding to open-ended questions. A 6-year-old child may not know how to respond to a question such as “Tell me about yourself,” but she may be able to answer a specific and direct question such as, “What grade are you in?” Other children may not respond well even to direct questions. Methods of obtaining information from children (if they are old enough to understand) include asking the child to draw a picture (e.g., “Can you draw a picture of yourself?”) and asking questions in the third person (e.g., “Why do you think the little boy in the picture looks sad?”) Getting the child to use his imagination can be fun for the child and can provide information for the doctor (e.g., “Let’s pretend that you have two wishes. What would they be?”) Gaining parental permission to speak to teachers and babysitters can also be helpful in getting information about a child.

Typically, adolescents worry about appearance, sexual orientation, sexually transmitted diseases, and substance abuse, concerns they may find difficult to discuss with their parents. Often, all that is required of the doctor is that she be nonjudgmental and able to reassure the adolescent that his or her thoughts are normal and common in people in this age group. With the exception of certain breaches of confidentiality (see

Chapter 26), it is also appropriate for the doctor to reassure the patient that such information will not be shared with his or her parents. Parents usually understand this need for privacy.

• GIVING INFORMATION TO PATIENTS

Patients are understandably reticent to ask questions about issues that are potentially embarrassing, such as sexual problems, or potentially fear provoking, such as laboratory test results. A doctor should anticipate such unspoken questions, verbalize them, and then answer them truthfully and completely.

Giving information to adult patients

In the United States, it is customary for adult patients to be told the complete truth about the diagnosis and prognosis of their illness. For example, if a dying patient asks the doctor how long he has to live, the doctor should answer truthfully. An accurate statement such as, “I do not know for sure, but most people at this stage of the illness usually live from 1 to 3 months,” is an appropriate response. A falsely reassuring response to this patient’s question (e.g., “Do not worry, we will take good care of you”) is paternalistic (

Kaba & Sooriakumaran, 2007) and not appropriate. The doctor should also avoid philosophical or religious statements that could be interpreted as patronizing (e.g., “No matter how long you live, you have had a very productive life”).

Table 24-1 provides a six-step strategy for giving bad news to patients (

Baile et al., 2000).

In some cultural groups, adult children protect elderly relatives from negative medical diagnoses and make medical decisions about their care (see

Chapter 20). Nevertheless, in the United States, information about a competent patient’s illness should be given directly to the patient and

not relayed through relatives. With the patient’s permission, the physician can tell relatives this information in conjunction with or after telling the patient, especially because relieving the fears of close relatives can bolster the patient’s support system.