Essentials of Diagnosis

- Two separate measurements of any combination of the following:

- Random plasma glucose ≥200 mg/dL with polydipsia, polyuria, polyphagia, and/or weight loss

- Fasting plasma glucose ≥126 mg/dL

- Two-hour oral glucose tolerance test ≥200 mg/dL after a 75-g glucose load

- A1C ≥6.5%. (by lab using a method that is NGSPcertified and standardized to the DCCT assay.

- Random plasma glucose ≥200 mg/dL with polydipsia, polyuria, polyphagia, and/or weight loss

General Considerations

The increasing acquisition of processed food combined with decreasing physical activity has led to an explosion in worldwide obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus, with the greatest rate of increase in the young. Diabetes is now the sixth (www.cdc.gov/diabetes) leading cause of death in the United States, and its treatment consumes one in every seven health care dollars, with 63% spent on inpatient care. It is a major cause of blindness, renal failure, lower extremity amputations, cardiovascular disease, and congenital malformations. With 90% of patients receiving their care from primary care physicians, diabetes is the epitome of a chronic disease requiring a multidisciplinary management approach.

Pathogenesis

Diabetes develops from a complex interaction of genetic and environmental factors. In type 1 diabetes this leads to destruction of the pancreatic β cells and loss of the body’s ability to produce insulin. Type 2 diabetes is the result of increasing cellular resistance to insulin, a process accelerated by obesity and inactivity. A very small percentage of diabetic patients may have latent autoimmune diabetes with an onset similar to type 2, but with destruction of the β cells, and a more rapid progression to insulin dependence.

Prevention

Diet and exercise have been shown to reduce the risk of developing type 2 diabetes by 58%. Several medications including metformin may also delay its onset by a more modest percentage. Tight control of hyperglycemia and blood pressure significantly reduce the complications of diabetes, and a sustained reduction in hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) is associated with significant cost savings within 1-2 years.

Motivating individuals to make lifestyle changes is difficult but cost-effective and safe, and can result in reduced obesity and hypertension and improvement of lipid profiles. A low-fat, high-fiber diet, modest exercise, and smoking cessation are modalities vastly superior to the complexities of the care of patients with diabetes and its complications.

Screening

Fasting glucose is the screening method of choice, although a random glucose is acceptable. The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends screening for diabetes in adults with hypertension. The American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommends screening every 3 years beginning at age 45 especially if BMI ≥25 kg/m2 . Testing should occur earlier and more frequently in patients with risk factors listed in Table 35-1.

| Family history of diabetes |

| Hypertension |

| Dyslipidemia (high triglycerides and low HDLs) |

| Obesity |

| High-risk ethnic or racial groups (African American, Hispanic, Native American) |

| Previous history of impaired glucose tolerance |

| Gestational diabetes, or birth of a child >9 lb |

| Habitually physically inactive |

| Cardiovascular disease |

| Polycystic ovarian disease |

A consensus panel has recommended screening of overweight children (weight >120% of ideal or a body mass index (BMI) >85th percentile) every 2 years beginning at age 10 or onset of puberty with two of the following risk factors:

Family history of diabetes in first- or second-degree relative

High-risk racial or ethnic group (Native Americans, African, Americans, Hispanics, or Pacific Islanders)

Signs of, or conditions associated with insulin resistance (eg. acanthosis nigricans, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and polycystic ovarian syndrome)

Universal screening in pregnancy is controversial. Table 35-2 lists the risk factors for which screening is recommended by the ADA and the diagnostic criteria in pregnancy.

| Risk Factors |

| Age >25 years |

| High-risk racial or ethnic group |

| Body mass index ≥25 |

| History of abnormal glucose tolerance test |

| Previous history of adverse pregnancy outcomes usually associated with gestational diabetes |

| Diabetes in a first-degree relative |

| Criteria for diagnosis |

| Initial screen: 1-h glucose tolerance test (GTT) |

| 50-g glucose load between 10 and 28 weeks’ gestation |

| Positive screen ≥135-140 mg/dL |

| Diagnosis: 3-h GTT with a 100-g glucose load |

| After an overnight fast with two abnormal values |

| Fasting ≥95 mg/dL |

| 1 h ≥190 mg/dL |

| 2 h ≥165 mg/dL |

| 3 h ≥140 mg/dL |

| Complications |

| Type 1: congenital abnormalities |

| Type 2: macrosomia |

Clinical Findings

The classic signs of diabetes are polyuria, polydypsia, and polyphagia, but first signs may be subtle and nonspecific. Patients with type 1 diabetes exhibit fatigue, malaise, nausea and vomiting, irritability and weight loss. Abdominal pain is a common complaint in children. They present early in the disease process, but usually are quite ill at presentation, often already ketoacidotic. Signs and symptoms of ketoacidosis include those associated with dehydration (dry skin and mucous membranes, decreased skin turgor, tachycardia, and hypotension), tachypnea, and labored respirations with the classic “fruity” breath, abdominal pain, and confusion.

In type 2 diabetes symptoms are seen well after onset of the disease and may be due to complications. The classic signs are still prominent, but patients may also complain of fatigue, irritability, drowsiness, blurred vision, numbness or tingling in the extremities, slow wound healing, and frequent infections of the skin, gums, or urinary tract including candidal infections.

The initial assessment for newly diagnosed diabetics is extensive (Table 35-3). The use of written checklists or questionnaires, electronic health records, or the assistance of a trained nurse or assistant can decrease physician time. Standing orders are an excellent way to make the visits more efficient and utilize nursing expertise (Table 35-4). It is important to update routine screening examinations (Papanicolaou [Pap], mammogram, colonoscopy) and ensure all immunizations are current (tetanus, pneumococcal, and yearly influenza vaccines). Interim visits focus attention on compliance and patients’ special issues with management (Table 35-5). Visit frequency is based on control of diabetes and the patient’s understanding and comfort. Patients initiating insulin therapy may require daily contact, by phone or e-mail. Those with poor control or making frequent changes may require weekly to monthly visits. When diabetes is well-controlled, visits are usually scheduled quarterly. Novel approaches to patient visits, such as group visits where several patients are seen simultaneously, maximize physician teaching time and allow sharing of ideas and information among the patients.

| History |

| Current and previous symptoms consistent with diabetes |

| Weight changes/history of obesity |

| Eating patterns/nutritional status (growth and development in children) |

| Exercise history and ability to exercise |

| Details of previous treatment; HbA1c and monitoring records |

| Current treatment (medications, diet) |

| Previous acute complications (Ketoacidosis, hypoglycemia) |

| History of infections particularly of skin, feet, and genitourinary system |

| History of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, coronary artery disease, and insulin resistance |

| Chronic complications (eg, retinopathy, nephropathy, neuropathy, sexual dysfunction, and gastrointestinal, vascular, or foot problems |

| History of gestational diabetes, large-for-gestational-age infants, or miscarriages |

| Medications and allergies |

| Family history of diabetes, endocrine disorders, or heart disease |

| Tobacco, alcohol, and drug use |

| Lifestyle, cultural, psychosocial, educational, and economic factors influencing control |

| Physical Examination |

| Height, weight, and body mass index (BMI) |

| Blood pressure (including orthostatic) |

| Ophthalmoscopic examination |

| Oral examination |

| Thyroid palpation |

| Cardiac examination |

| Evaluation of pulses, including carotid |

| Abdominal examination |

| Skin examination (including injection sites if applicable) |

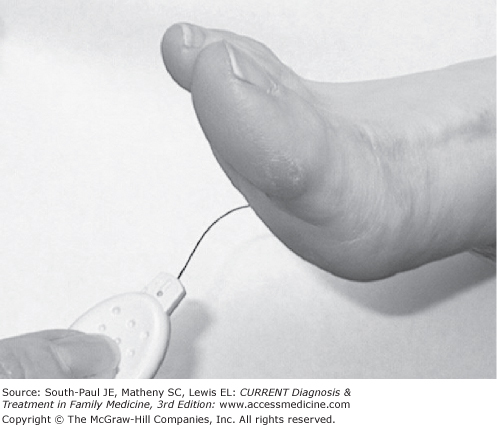

| Neurologic examination with particular attention to reflexes, vibratory, senses, light touch (monofilament examination of both feet), and proprioception |

| 1. Update the electronic record or place an updated flowsheet in the patient’s chart. |

| 2. Monitor and record blood pressure in the same arm at each visit. |

| 3. Measure and record the patient’s weight. |

| 4. If HbA1c has not been evaluated in the past 6 mo, complete arequisition and attach to the patient’s chart. |

| 5. If urinalysis and microalbumin testing have not been done in the past year: |

| a. Perform a urine dipstick and record the results on the flowsheet. |

| b. Complete a requisition for a urine microalbumin test and attach it to the patient’s chart. |

| 6. If a lipid profile has not been obtained in the past year, complete a requisition and attach it to the patient’s chart. |

| 7. If a dilated eye examination has not been performed in the past year, complete a referral for an ophthalmology examination and attach it to the patient’s chart. |

| 8. Ask the patient to remove his/her shoes and socks. |

| a. Palpate dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial pulses. |

| b. Inspect the skin for any skin breakdown. |

| c. Record the findings on the patient’s flowsheet. |

| 9. Check to see if patient has received a pneumococcal vaccine, a dT or Tdap vaccine in the last 10 years, and a flu shot for the current season. If patient has not received the flu shot, administer following standard clinic protocol. |

| Physician Signature: _______________Date: ____________ |

| History |

| Hypoglycemic episodes |

| Glucose monitoring results |

| Adjustments in therapeutic regimen |

| Complications |

| Medications |

| Psychosocial issues |

| Lifestyle changes |

| Patient goals and motivation |

| Physical Examination |

| Weight and BMI |

| Blood pressure |

| Funduscopic examination |

| Cardiac examination |

| Brief skin examination |

| Foot evaluation (visualization, pedal pulses, and monofilament examination [see Figure 35-1]) |

Initial and yearly labs include fasting glucose, fasting lipid profile, serum electrolytes and blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, urinalysis, and microalbumin. Evaluation of thyroid-stimulating hormone may be indicated as concurrent hypothyroidism is common especially in women. Depending on age and duration of disease an electrocardiogram (ECG) may be performed, but as microalbuminuria is a marker for cardiovascular disease, an ECG should be performed once microalbuminuria is detected. HgbA1c is measured every 3 months. Random microalbumin levels or microalbumin/ creatinine ratios may be used for screening and/or monitoring, but patients may require a 24-hour urine for protein and creatinine clearance when there are significant changes. Common findings are elevations in glucose, HgbA1c, triglycerides, BUN and creatinine, and microalbumin with decreased HDL (high-density lipoprotein) cholesterol.

Complications

Preventing and delaying progression of all complications in patients with diabetes is dependent on lifestyle modification, tight control of blood glucose and blood pressure, and smoking cessation. The ACCORD trial, however, found that intensive glycemic control (HgbA1c ≤6%) did not lower the incidence of adverse microvascular outcomes.

Ketoacidosis occurs when there is insufficient insulin to meet the body’s needs, resulting in increased gluconeogenesis, fatty acid oxidation, and ketogenesis. This leads to metabolic acidosis, osmotic diuresis, and dehydration. Ketoacidosis is one of the leading causes of death in children with diabetes with an incidence in children of about 8 per 100 person-years. It increases with age in girls, and is highest for children with poor control, inadequate insurance, or psychiatric disorders.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree