Deep Inferior Epigastric Perforator Flap Breast Reconstruction after Mastectomy

Adeyiza O. Momoh

DEFINITION

Autologous reconstruction techniques after mastectomy are well-established options for breast reconstruction. Although over the years multiple flap options for reconstruction have been described, abdominal-based flaps continue to be the workhorse for autologous breast reconstruction. Abdominal flaps provide distinct advantages over implant-based reconstruction including a natural contour, superior symmetry and appearance of the reconstructed breast mound, and higher patient satisfaction.1,2 A secondary benefit of these flaps is the improvement they provide to the abdominal contour. Hartrampf et al.3 first described the pedicled transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous (TRAM) flap in 1982, with its benefits of providing a soft, ptotic, aesthetically pleasing reconstruction that closely approximates the natural breast. Technical advancements and the continued quest to improve on flap perfusion and minimize donor site morbidity led to the introduction of the deep inferior epigastric perforator (DIEP) flap by Koshima and Soeda4 in 1989 with later popularization by Allen and Treece5 in 1994. The DIEP flap has gained in popularity over the years, and the potential benefits it offers include less abdominal wall weakness, bulging, and hernias.6, 7, 8

ANATOMY

The DIEP flap is an adipocutaneous flap based on intramuscular perforators from the deep inferior epigastric artery (DIEA) and deep inferior epigastric vein (DIEV).

The DIEA and DIEV originate from the external iliac vessels in the groin and course superomedially toward the lateral border of the rectus abdominis muscle.

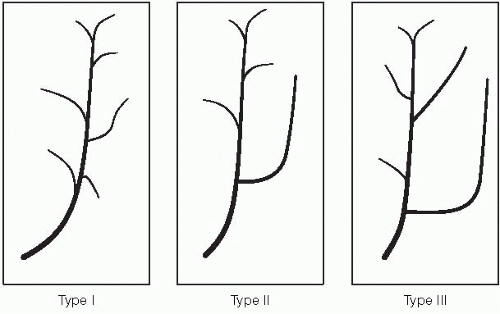

Deep to the rectus abdominis muscle, the DIEA and DIEV most commonly bifurcate (type II branching pattern) in the vicinity of the arcuate line and join up with the superior epigastric vessels above the umbilicus.

Other encountered branching patterns are the type I with no branching and type III with trifurcating vessels (FIG 1).

Perforators to the lower abdominal skin and adipose tissue come off the pedicle at multiple levels and are referred to as medial or lateral rows of perforators, indicating their relative position within the rectus/entry point into the flap.

Most perforators are found within a 10-cm radius from the umbilicus.

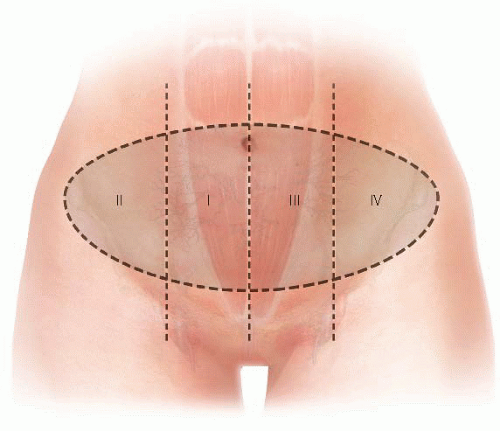

Zones of perfusion based on fluorescent perfusion studies9 are illustrated in FIG 2—illustration with zones transposed onto rectus/pedicle.

In general, perfusion of the hemiabdominal flap ipsilateral to the perforators (zones I and II) is stronger than it is to the contralateral abdominal flap across the midline (zones III and IV).

Medial row perforators have a greater likelihood of perfusing tissue across the midline than do lateral row perforators.

In contrast, lateral row perforators have a greater likelihood of perfusing the most lateral extent of the ipsilateral hemiabdominal flap than do medial row perforators.

Medial and lateral rows of perforators communicate via a subdermal plexus.

There is also communication between DIEA and DIEV system and the superficial inferior epigastric artery (SIEA) and superficial inferior epigastric vein (SIEV) system.

The SIEV is the dominant outflow vessel for the lower abdomen in many patients.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

A thorough history and physical examination are critical in preparing for reconstruction.

Pertinent aspects of the history include previous abdominal or chest wall operations and medical conditions that would preclude patients from a lengthy operation under general anesthesia.”

A focused abdominal examination evaluating the amount of lower abdominal adipose tissue and the location of surgical scars if present

A team-based approach involving surgeons, anesthesiologists, primary care physicians, and other specialists such as cardiologists, as needed, ensures that patients are evaluated as a whole and all key concerns are addressed.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

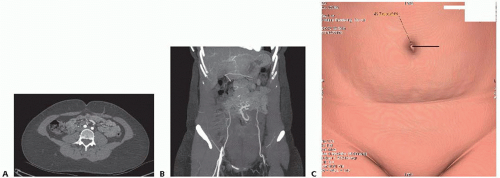

Preoperative computed tomography (CT) angiography of the donor site has been advocated in recent years. The preoperative scans provide a road map for flap perforators, with information on perforator location, size, and distribution (FIG 3).

In patients with long low transverse abdominal incisions, the scans also allow for the assessment of continuity of the flap pedicle beyond the incision.

Information gathered from scans has been shown to decrease operative times.10 CT scans, however, are not an absolute requirement for preoperative planning.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

In consulting with patients, decisions about the timing of reconstruction (immediately after mastectomy or delayed) and the type of reconstruction are made, taking patient factors and tumor characteristics into consideration.

Patient factors of significance include the following:

Patient preference

Body habitus or the availability of abdominal donor tissue

Body mass index

Smoking history

History of previous abdominal operations that compromise the vascular pedicle or donor site

Medical comorbidities that would preclude patients from undergoing a lengthy operation

Tumor characteristics as they relate to the following:

The need for postmastectomy radiation therapy or

The need for close postmastectomy surveillance prior to reconstruction

In general, patients known to require postmastectomy radiation therapy are reconstructed in a delayed fashion to avoid the detrimental effects of radiation on flaps. A history of radiation therapy also serves as a relative indication for use of an autologous form of reconstruction, as implant reconstructions in the setting of radiation are prone to higher rates of complications and failure.

Preoperative Planning

In addition to basic labs, patients should be type and screened, particularly in cases of bilateral reconstructions.

All anticoagulant and antiplatelet medications should be stopped a week prior to the operation. Warfarin can be bridged with enoxaparin also a week prior.

Smokers are required to quit for a minimum of 4 weeks prior.

Patients receive preoperative antibiotics with intraoperative redosing.

Patients receive deep vein thrombosis (DVT) prophylaxis with use of a pneumatic compression device and subcutaneous heparin at the beginning of the case.

Positioning

Marking/positioning

Preoperative markings of the breast and abdomen are performed with the patient in the upright position.

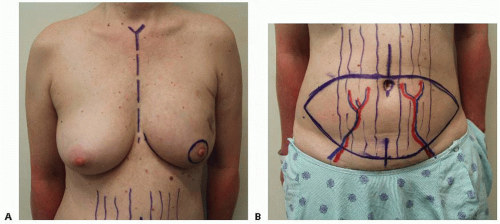

Key landmarks for the breast marked are the chest midline, inframammary fold, and a periareolar marking in the case of a skin-sparing mastectomy. The breast base width is also measured (FIG 4A).

The upper marking for the abdominal flap is made at or just above the umbilicus with the location of perforators on preoperative imaging, providing some guidance. The breast base width is used to mark the potential vertical height/distance from the upper marking to the lower marking. The lower marking is then made to complete the elliptical pattern (FIG 4B).

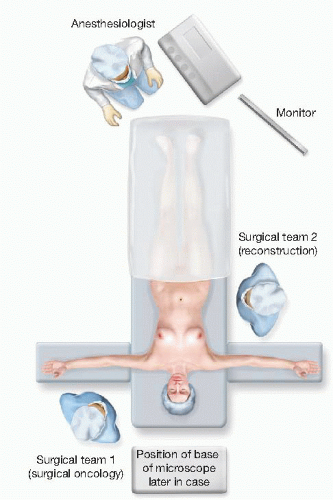

Patient positioning in the operating room (OR) is supine and the table is turned 180 degrees from the anesthesiologist, providing better access for two surgical teams (FIG 5).

TECHNIQUES

FLAP HARVEST

Skin preparation with clipping is performed as needed.

The breasts and abdomen are prepped and draped in a sterile fashion.

The upper abdominal incision is made with a scalpel, and dissection through the adipose tissue down to anterior abdominal wall fascia is performed with electrocautery.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree