The Miasma of Politics

Unfortunately, as you exercise your talents as a healthcare or physician leader, your patience will likely be tested by overtly political behavior or at least the annoyance of the day-to-day dealings of office politics. It is important that healthcare managers avoid political quagmires in the workplace in the interest of providing stellar, progressive services to patients and to the healthcare organization.

Office politics causes several significant problems for the healthcare manager and the healthcare organization as a whole.

Politics inhibits productivity. Generally speaking, workers are not particularly motivated to perform well for individuals who are more politics-minded than performance-minded. A great deal of time is spent avoiding power plays and preparing for counteractions. Consequently, productivity suffers, and worst of all the patient is deprived of receiving the full range of services the healthcare organization is capable of providing.

Politics stifles creativity. Because politics can promote paranoia, team members may be reluctant to share new ideas or work in a group process that encourages creativity or innovation. As a result, staff growth and development are compromised or top performers relocate to a less political or, better yet, nonpolitical environment. Again, the patient and the organization suffer.

Politics cripples teamwork. Individuals who are suspicious of each other and have limited respect for each other end up resenting one another and avoiding open communication. Politics destroys allegiance and loyalty among team members and the overall objective of the team or organization. Group morale begins to diminish until finally individual employee motivation begins to erode.

Overt negative politics alters communication. Overt negative politics includes altered messages, altered presentation of messages, or flat-out noncommunication in certain situations. Politics often begin after a third party enters the picture, creating an unbalanced dynamic and opportunity for two people to discuss a third person—often in an uncomplimentary manner.

Whenever a premium is placed on politics as opposed to performance in the healthcare environment, the team or department finds itself at risk of falling apart—or at least beginning to be much less productive. Five basic indicators that can signal overtly political behavior include

Double-talk: Individuals who tell one story to one person and an entirely different story to another are double-talkers. Their motives may be to cover the bases on a particular issue, deliberately create disharmony, or simply try to pit two people against each other.

Backstabbing: Backstabbers overtly pledge allegiance to you and your ideas but covertly downplay them and insult your intelligence.

Power mongering: Power mongers try to control everything. These individuals are also called turf protectors or empire builders because they often use resources and territory as the principal focus of their subversive efforts. As a healthcare manager, you may fall prey to a power monger’s claim of being in charge of something that in fact he or she has no control of.

Victim’s role: Some individuals claim that the organization is out to get them and that you had better watch yourself. People with this mindset are more interested in their own survival than in assisting fellow workers through the healthcare mission.

Game playing: Game players use phony behavior in trying to engender support. They play games with fellow staff as well.

As a physician leader, what are the best strategies for dealing with politics? Whether the politician is a member of your staff or a colleague, these five strategies may be useful:

Avoidance is easy. Simply try to stay out of the way of political behavior whenever possible. If avoidance is not feasible on a daily basis, keep all contact on a business level and discuss only business issues. If someone tries invariably to shift the focus to a politically oriented level, firmly return them to the issue at hand. Remember that your primary managerial responsibility is to bolster staff motivation and productivity while contributing to your facility’s goal of high-quality patient care.

Confront the person and let her know that you are aware of her political intent. For example, if you are asked a loaded question, simply counter by asking another question such as, “Why are you asking me that?” You risk incurring wrath, but you at least discourage overtly political behavior.

Disclosure and support works if the troublesome individual is someone on the management team or someone who reports to your own manager. Simply present evidence of the political behavior to your supervisor, without judgment or opinion. Use objective reporting. For instance, “You know, a funny thing happened the other day. I was talking to (name), who seemed persistent in wanting to discuss (topic).” This approach indicates your apprehension in dealing with this individual and signals your need for specific assistance.

With direct input from your own boss, you can actively enlist support. Simply tell your boss—likely a seasoned executive who has dealt with similar games and gambits—about the problem, review the evidence, and ask directly for assistance: “What would you do if you had this situation?” (If you perceive your boss to exhibit excessively political behavior, you may want to request the help of another mentor within the organization in dealing with this behavior.)

Gather documentation as evidence of political behavior by colleagues or staff. The more examples you collect, the better case you can make for termination (if the person is staff ) or for limited contact (if the source is a colleague). Record evidence or examples of notable political behavior, and be sure to handle reports tactfully.

Recognizing Intradepartmental Conflict

Despite a healthcare manager’s best efforts to establish trust throughout his/her work group and to avoid potential conflict, human nature unfortunately creates occasions for intradepartmental conflict. Intradepartmental conflict is any conflict that takes place within a single department or work group.

Initially, intradepartmental conflict takes place on an interpersonal basis. Interpersonal conflict, particularly within a work group, is potentially the most damaging type of problem a healthcare manager can deal with. If interpersonal conflict exists within a department and is not abated and resolved correctly, it will have drastic negative consequences for the entire department—even implosion.

Numerous indicators signal intradepartmental conflict. Use your instincts and observations to examine the conflict in a cause-and-effect fashion. Following is a list of potential symptoms, causes, and effects on your department:

Anger: Interpersonal adversity, loss of temper, lack of patience, or flat-out confrontational behavior may all be exhibited in certain kinds of interpersonal conflict.

Avoidance: When an individual declines to work with someone or simply avoids contact with that person, work may not be done and the team processes may be compromised. Avoidance is more subtle than anger and often more common.

Blame: One individual may claim another person is entirely responsible for a mistake. Often the person blaming is attempting to cover for his/her own inability or failure to perform. Blaming creates hostility among team members and betrays basic trust and pride in the organization.

Excuse making: One individual uses another’s behavior as a reason for not performing a particular task. The individual may focus specifically on a personality nuance as being the problem that gets in the way of accomplishment. Another form of making excuses is to rationalize the negative behavior of others.

Isolation and fragmentation: Certain team members may exclude one or more players because of personality conflict. Isolation jeopardizes the group participation process, and ultimately, one or more individuals may withdraw the resources needed to get a job done. Extreme isolation may lead workers to organize into factions. This fragmentation can become particularly detrimental in any group process, especially one that requires quick, efficient response.

Confrontation: Argumentative personality types use intimidation and confrontation to disrupt process, waste time, and demoralize others.

Criticism: Continuous nit-picking severely diminishes morale. Ironically, others often respond to constant criticism by becoming defensive and in turn critical of the chronic criticizer.

Erosion of performance: The quality and efficiency of work diminishes, resulting in ill feelings and costly overtime. Some staff begin to look for another workplace if the situation is not corrected by the manager.

Regression: A performance continues to erode, worker may do less and less, bringing work process to a grinding halt. In an era in which health care must be progressive, every employee’s performance must contribute to its maximum potential.

Resolving Intradepartmental Conflict

Many organizations have recommended approaches to dealing with interdepartmental conflict. As you gain more experience as a manager and see what does (and doesn’t) work, you’re sure to develop your own ways of resolving disagreements between staff members. The following 6-step process can adapt well to a multitude of situations and organizationally recommended processes:

Go on a fact-finding mission. Begin any effort to resolve intradepartmental conflict by performing thorough fact-finding every step of the way. Fact-finding is the process of collecting information from all involved parties before arriving at a decision. For example, when an intradepartmental conflict takes place between two individuals, you may want to investigate by discussing the situation with both parties separately and by asking them the same two questions: what they think the problem and root cause may be, and how the situation can be resolved. At that point, bring both parties together, present both ideas for resolution, and once again state your optimism for correction as well as your refusal to tolerate further interpersonal conflict.

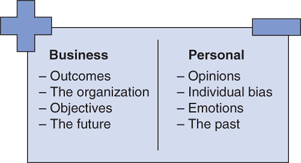

Separate issues into two categories. First identify business-related attributes of the problem—business outcomes, performance dimensions, and technical areas. Then list personal issues that may bear on the conflict (Figure 4–1). Review this information completely with the involved party and reach consensus on the facts of the issues. If no one acknowledges the facts, you may have to state more directly your belief in their validity and supplement that statement with the pledge that you will not accept this behavior any longer.

Move the discussion to performance. Focus specifically on the business effects from the conflict. Cite work that is not being done; explain how the employee’s (or group’s) behavior affects other department members and how this behavior interferes with others’ getting their jobs done. Discuss further how this behavior affects other departments and, most important, patients.

Ask why this behavior has taken place and how it might be corrected. Try to get to the bottom of what the parties believe is contributing to the problem and how the cause can be alleviated. Following this discussion, present your own ideas on why the problem exists; however, spend most of your discussion on how the problem must be remedied.

State clearly, concisely, and resolutely your expectations, standards, and policies for future action. Explain what you accept as satisfactory behavior and what you consider poor performance or interpersonal conflict. Future actions may include probation or other disciplinary action, including termination.

Express your confidence that the situation will be corrected, and ask whether particular assistance is needed to do so. Try to strike a delicate balance between expressing optimism that the situation can be corrected and underscoring the fact that continued poor performance and intradepartmental conflict will not be tolerated under any conditions. Interpersonal conflict is complex and can hinder progressive action. As a manager, you must deal with it resolutely and in a timely fashion so that the majority of your department is not adversely affected.

Leading Through Conflict, Change, and Crisis

Invariably, healthcare managers must make the tough calls. This includes taking disciplinary action (including terminating employees and putting employees on probation), mediating conflict, dealing with internal customers, and an array of other potentially volatile situations. No matter what your technical background might be or which department you work in, inevitably you will have to manage tough situations—dissatisfied or even hostile customer/patients, for example. Because these situations erupt immediately, you must be prepared with techniques to manage them.

This section deals directly and practically with an assortment of problems a newly appointed healthcare manager can encounter. Although no one solution meets all problems, the information in this chapter should prove to be a useful guide as you attempt to manage those gray areas inherent to tough situations. By adopting the strategies most suitable to your management style and work environment, you will take a proactive approach to problem solving and conflict management.

Next, the section will discuss the symptoms of conflict within the workplace and pragmatic ways of resolving conflict among employees. Conflict resolution involves use of fact-finding processes, so an adaptable approach to fact-finding and a strategy for implementing conflict resolution systems into your responsibilities will be offered. Some insight will be provided on counseling employees and resolving conflict in one-on-one counseling situations.

Because probation and termination are unpleasant realities of management responsibilities, these issues will be addressed specifically when and how to fire someone. The section will conclude with a discussion on how to resolve customer/patient complaints successfully and efficiently. Source material is drawn from some of the most challenging complaints from physicians and union employees.

The Establishment of Trust

Regardless of the size of a healthcare work group, there are two elements that cannot be fully regained if lost. One is trust, defined here as the sense of integrity that exists between employees and their supervisor. If trust is lost or diminished through action and negative consequence, it is unlikely that it can be regained at its original level. The other element, pride, is defined here as a sense of allegiance and high esteem that pervades the work group. Both trust and pride are valued commodities that link the supervisor and the individual employee. Trust, however, is the overriding motivator.

This section will discuss ways to establish trust in your work group. It is essential that you embrace these guidelines and try to apply them to your everyday activities. Unless employees have trust in your leadership ability, they may not be motivated to follow even the clearest direction. The consequence is that time will be wasted unnecessarily by challenges to your authority or misguided questioning of your decisions.

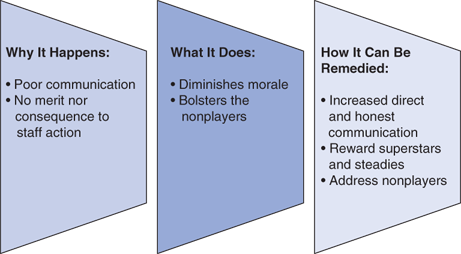

You begin to establish trust on day 1 of your tenure as a manager. As alluded to briefly at the outset of this chapter, loss of trust usually results in the breakdown of group harmony and productivity; ultimately, this loss of trust could lead to a manager’s termination (Figure 4–2). Many new managers are filling vacancies created by predecessors who in failing to elicit trust from staff failed ultimately to elicit high-quality outputs. In the long run, the establishment of trust could be your most important asset as a healthcare manager.

Communication is the cornerstone for establishment of trust. If you demonstrate a clear, open channel of communication, each employee has the opportunity to explore the parameters of his or her relationship with you. Apprehension can be addressed, questions can be answered, and directions can be ascertained through clear communication. Employees can gain a sense of their new leader’s style through this mode of communication. Without it, the perception can arise that game playing or selective communication is the new manager’s modus operandi.

Start building your communication strategy by remembering to ask questions frequently to all members of your staff. Utilize the questions provided in this book, and focus specifically on asking them what can be done to make the organization better and what they need from you in order to become better workers. The second approach is to ensure that monthly department meetings are held so that employees can discuss work progress and you can review your goals and objectives for the organization. The third strategy is to try to analyze which staff members need the most (or least) communication. Make an entry in your manager’s logbook about how often you will meet with each individual on a one-to-one, interpersonal basis. This will give more reticent staff members an opportunity to discuss issues they might not feel comfortable addressing openly in a meeting.

Many managers advocate an open-door policy. This is a good idea in theory, but in practice it requires some fine-tuning. Establish certain hours during which your door is indeed open and workers can have access to you. Ask your assistant or secretary (if you have one) to screen employee requests for meetings with you and to schedule them based on priority of need.

In addition to an open-door policy, apply the management-by-walking-around techniques. This strategy mandates setting aside a certain amount of time each day to simply stroll around your assigned area of responsibility, make sure that individuals have access to you, and ask questions in a nonthreatening manner. Again, this keeps the communication lines open while visibly reinforcing trust and making you accessible to your employees.

Another way to establish trust is to pursue opportunities to review the past. Discuss with your staff areas in which their past performance was good or inferior. Ask for their suggestions on how improvement might be made. This can be done within the context of group performance or individual performance.

Encourage staff to be direct and candid about their assessment of past performance as a group. Keep the conversation focused on performance, not on personality-based issues. For example, discourage reference to your predecessor’s personality, that of individuals within the department, or other potentially explosive issues. In emphasizing performance, you discover areas for improvement and crystallize specific methods on how to improve performance throughout the department and within individual work roles.

Discussion about “what we are doing wrong” also helps establish trust. By acknowledging that the department is not perfect and that you as a manager will not be perfect, you remind everyone involved that you share the human quality of imperfection. This listing of mistakes and opportunities for improvement is a good opener in establishing trust. Most healthcare workers are perfectionists who strive for ideal outcomes in all their assigned responsibilities. Accordingly, they are well versed not only on what goes wrong but why it went wrong. By reviewing mistakes and concentrating on where a problem might exist, your staff might understand your identity with them resonantly and therefore feel free to share their thoughts on areas for improvement.

To use this strategy in a practical application, have all members in your department or work group brainstorm areas for improvement. Using an easel (as a group) or individual notepads, they can divide the page into three columns. In the first column list is the event or application that needs improvement. For the second column, ask your staff to focus in on things they can control or are doing right relative to the problems/challenges cited in column 1. Also ask for suggestions for improvement as part of a commitment to the continuous quality improvement process to your work activities. In the third column, have them list situations and circumstances of which the department has either limited or no control.

Figure 4–3 shows an example of this charting system as used by a hospital’s human resource department. The first column lists challenges; the second contains entries of things within their control; the third indicates problems with a project or process they feel are out of their control.

FIGURE 4–3.

Sample of change/crisis charting.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree