Data-Gathering and Relationship-Building Skills: Introduction

What we observe is not nature itself, but nature exposed to our method of questioning.

Werner Heisenberg, 1958

In Chapter 1, we introduced two types of interviewing skills: “patient-centered skills” and “clinician-centered skills.” Patient-centered interviewing skills are used at the beginning of the interaction to gather unique symptom and personal information from the patient; they are also used throughout the interview to build and maintain the clinician-patient relationship. By focusing on what the patient has already introduced, patient-centered skills encourage the patient’s lead. A useful analogy is to view each individual bit of new information, from interviewer or patient, as being placed on a table between them. When using patient-centered interviewing skills all new bits of information are placed on the table by the patient. To be certain, clinicians will influence and have an effect upon the conversation by asking the patient to say more about a bit of information on the table, for example, but a patient-centered approach minimizes the clinician’s impact. Clinician-centered interviewing skills are used in the middle of the interview to fill in the details of the patient’s story, and to collect required routine data. Used prematurely, or excessively, clinician-centered skills can contaminate the patient’s story with what is on the clinician’s mind. This is sometimes referred to as premature hypothesis testing, which can lead to an inaccurate or biased view of the problem(s) and how best to deal with them.

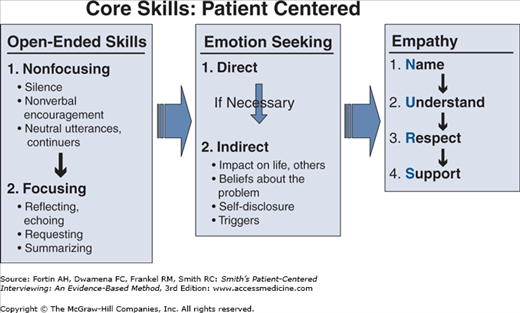

In this chapter, we focus on the specific data-gathering and relationship-building skills that are the interviewer’s tools on a moment-to-moment basis (see Figure 2-1). These skills are patient-centered when they are used to facilitate the patient’s telling her or his story with minimal interference from the interviewer’s thoughts and ideas. They are clinician-centered when used to focus on a topic not yet introduced by the patient. For example, when “health” or “wife” have not been mentioned or alluded to by the patient, it would not be patient-centered to say, “Tell me about your health” (an open-ended request) or “What are your feelings about your wife” (direct emotion seeking). Clinician-centered inquiry that introduces new information is appropriate during the middle portion of the interview where one frequently must introduce ideas and concepts not yet mentioned by the patient—using open-ended skills (frequently), emotion-seeking skills (occasionally), and, primarily, closed-ended skills.

Data-Gathering Skills

Open-ended skills are used to encourage the patient to freely express what is on her or his mind. There are two types of open-ended skills: (1) nonfocusing open-ended skills (silence, nonverbal encouragement, and neutral utterances) and (2) focusing open-ended skills (echoing, open-ended requests, summary). Nonfocusing skills are used throughout the interview to encourage the patient to talk freely. They are critical at the beginning of the interview. As the patient talks, she or he will introduce many topics that may or may not coalesce into a coherent story. As long as the patient is giving a coherent and nonrepetitive story, nonfocusing skills are effective. Focusing open-ended skills will be necessary for most patients to help them develop their narrative beyond the opening statement. Focusing skills are used to invite the patient to talk more about topics that have already been mentioned. They can also help the interviewer restore balance when the patient’s narrative becomes too chaotic or overwhelming.

Saying nothing while continuing to be nonverbally attentive (using eye contact and open body posture) prompts the patient to fill the space and signals that you are interested in what she or he is saying. For example, the clinician’s silence in the following vignette allows the patient to express what is really on his mind:

Patient: | … and it rolled down and hit me here (pause). |

Clinician: | (attentive but silent for 5 seconds) |

Patient: | … so I called you, thinking you’d be in, but you were not. I was hoping to have heard from you sooner … |

Silence can make some patients uncomfortable, a discomfort they may indicate by shifting about or looking away. If 5 or so seconds of silence do not prompt further information or the patient appears uncomfortable, move on to another skill.

Nonverbal encouragement also urges patients to talk freely. It is commonplace in everyday interactions and is easier to use than silence. Typically, the interviewer gestures with the hand (rotatory motion to continue), makes a sympathetic facial expression (of expectation to continue), nods, or simply indicates by body language that the patient should continue speaking (leaning forward):

Patient: | … so that it hurt his feelings (pause). |

Clinician: | (leans forward with expectant expression) |

Patient: | Well then I felt bad too and … |

Neutral utterances are brief, noncommittal statements such as “I see,” “Uh-huh,” “Yes,” or “Mmm” that encourage the patient to talk in an open-ended manner:

Patient: | … and later the pain went in the front part, right here … |

Clinician: | Uh-huh. |

Patient: | Yeah, and it hurt like crazy. |

Clinician: | Mmm. |

Reflection (echoing) signals that the interviewer has heard what the patient said by repeating a word or phrase that was just said. It encourages the patient to proceed and focuses the patient on the word or phrase echoed.

Patient: | After the pain let up, I still couldn’t find him. |

Clinician: | The pain? (Invites the patient to talk more about the symptom of pain) – OR – Couldn’t find him? (Invites the patient to describe a personal aspect of his story) |

Open-ended requests can be general, for example, “Tell me more” or “Go on,” or they can focus the patient in an already mentioned area that the interviewer wants to expand upon, such as “Tell me more about the daughter you mentioned.”

Patient: | Then my pain came back because I couldn’t afford the medicine. |

Clinician: | Go on (encourages patient to continue without additional focusing). – OR – Tell me about not affording it (focuses patient on the personal problem). – OR – Tell me about the pain (focuses patient on a symptom). |

Like other focusing skills, open-ended requests should be used to move patients to deeper levels of their stories by focusing on something that the patient has already mentioned. They should not be used to direct the patient to a topic they have not already mentioned, for example, “Tell me about your family” when the patient has not said anything about her or his family.

Instead of echoing only a word or phrase, the interviewer echoes a wider range of talk by summarizing it. This invites the patient to focus on the material summarized and express deeper levels of her or his story. It signals that she or he has been heard and that she or he should proceed beyond that point.

Patient: | (Long story about difficulty getting in to see clinician) |

Clinician: | So you had the nausea but couldn’t get me on the phone. Then it got worse and your wife still couldn’t get a hold of me until today. |

Patient: | Yeah, I was really more upset than sick by now. |

As shown in the examples above, focusing skills pinpoint areas for further exploration whether they involve symptoms or personal context. They allow you to actively develop a coherent, narrative thread in the patient’s words and to take control of the interview if necessary, while remaining patient centered.

You can also refocus the patient on an important topic that may have slipped by too quickly. Often patients mention a loaded topic, such as death, but rapidly move away from it. You can return to the topic by saying, for example, “You mentioned death a minute ago, tell me more about that.” Because the patient initially introduced the topic of death, this action is patient-centered even though it interrupts the immediate thread of conversation. On the other hand, to be most patient centered, avoid shifting away from important personal topics back to physical symptoms already mentioned. By using these skills to learn more about information already introduced by the patient, you obtain a story that originates more completely from the patient’s mind, and is less contaminated by the interviewer’s thoughts and actions.

Closed-ended questions typically are answered with yes, no, or a brief response. They are used primarily to confirm or refute specific issues that arise in your mind. This makes them ideal for the middle of the interview in which you have to take the lead to obtain many specific details from the patient. Closed-ended questions enhance the precision of information. They are counterproductive when they discourage information originating in the patient’s mind and force the patient to respond to the clinician’s concerns and ideas. Used excessively or inappropriately, closed-ended skills also can have a deleterious effect upon the clinician–patient relationship and greatly diminish the quantity and quality of data about the patient. Patients who are chronically exposed to this type of questioning during the encounter often feel as though they are being interrogated rather than interviewed and they are less satisfied with the clinician and the interaction.

There are two types of closed-ended skills, very familiar and reflexive:

These questions are asked with a specific issue to be answered. They can be used to clarify a patient’s statement or introduce a new topic.

Patient: | My pain is right here. |

Clinician: | Is it just in your left arm? – OR – Did you have shortness of breath with the pain? |

Patient: | No. |

Clinician: | Did you come in this morning? |

Patient: | Yes. |

These questions also direct the patient to answer with a word or phrase.

Clinician: | How old are you? |

Patient: | Thirty one. |

Clinician: | How high was the fever? |

Patient: | I don’t know. – OR – Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|