Cytoreductive Surgery and Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy for Peritoneal Surface Dissemination of Colorectal Cancer

Reese W. Randle

Konstantinos I. Votanopoulos

Edward A. Levine

Perry Shen

John H. Stewart IV

DEFINITION

The term peritoneal surface disease (PSD) describes the intraabdominal dissemination of neoplasms to peritoneal surfaces and is a term complementary to peritoneal carcinomatosis.

Cytoreductive surgery (CRS) and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) have been shown to be effective treatment options for a variety of epithelial primaries. The scope of this chapter is to analyze the role of CRS/HIPEC in the management of selected colon cancer patients with peritoneal dissemination.

The operation is a two-step process:

Surgical resection (CRS) of involved organs and peritoneal surfaces, followed by

Delivery of heated chemotherapy (HIPEC) to the peritoneal cavity

During HIPEC, a heated chemotherapy solution is circulated in the abdominal cavity to treat any cancer cells that may remain after CRS. Delivering chemotherapy at the time of cytoreduction allows a more complete distribution in the peritoneal cavity and exposes tumor-to-drug concentrations higher than that achieved with systemic chemotherapy.

Thus, the theoretical advantage of CRS/HIPEC, which is now routinely performed in specialized centers, is that it treats macroscopic diseases surgically and microscopic diseases pharmacologically. The results of a prospective randomized trial testing this hypothesis are expected to be released soon.

The goal for CRS/HIPEC applied to PSD from colon cancer is the complete cytoreduction of all macroscopic disease prior to perfusion with HIPEC. Therefore, appropriate candidates are identified based not only on their ability to tolerate aggressive CRS but also on the likelihood of obtaining a complete cytoreduction.

Careful selection of patients can help ensure that only those who can expect to have the greatest benefits are subjected to the inherent risks of this treatment paradigm.

PATIENT SELECTION

Patient selection is based predominantly on the extent of disease and the functional reserves of the patient.

Preoperative evaluation includes complete history and physical, review of previously obtained pathology, and infused computed tomography (CT) of the chest abdomen and pelvis or dedicated abdominal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Preoperative lab work includes blood counts, electrolytes, liver function panel, and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) levels.

Our selection criteria include the following:

The patient is medically fit to undergo CRS/HIPEC without signs of kidney, liver, or bone marrow dysfunction preoperatively.

The patient’s Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) functional status is less than or equal to 2.

There is no extraabdominal disease or retroperitoneal disease.

There is low-volume peritoneal disease (preferably a peritoneal carcinomatosis index less than 14) that is potentially completely resectable.

Any parenchymal hepatic metastasis should be limited and should not require anatomic liver resection.

Malignant ascites and bowel obstructions are predictors of incomplete resection and worse overall survival.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Infused CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis is the standard preoperative imaging study and helps to rule out extraabdominal disease, extensive hepatic metastases, and insurmountable small bowel involvement. Sites of impending obstruction may also be identified.

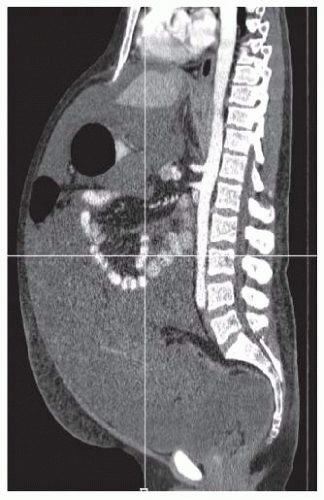

Although the sensitivity of CT scan for detecting PSD is low, it is useful in determining overall operability. Solid disease components may be hidden in patients with large volumes of malignant ascites (FIG 1).

MRI may detect PSD with up to 100% sensitivity, yet has a significantly high false-positive rate, especially after prior operations. This is because MRI is incapable of recognizing a difference between scar tissue and recurrent PSD.

Positron emission tomography (PET) is rarely used given that sensitivity and specificity are prohibitively low, especially in patients with limited disease.

Endoscopy can allow clinicians to tattoo second colonic primaries in less than 5% of the patients. Endoscopic ultrasonography is unlikely to change the management of these patients.

Diagnostic laparoscopy can assist in determining the extent and stage of PSD prior to CRS/HIPEC.

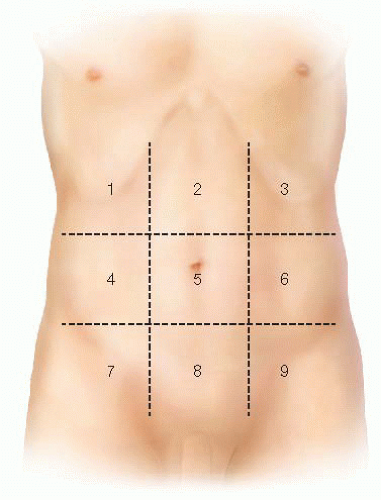

The peritoneal carcinomatosis index (PCI) is the most commonly used staging system for PSD. It provides a way to

standardize the extent of disease. It has been shown to have prognostic value and certain scores have been used as a cutoff in deciding when CRS/HIPEC is appropriate. Calculating the PCI involves dividing the abdomen into nine regions and the small bowel into four regions. For each region, a score of 0 (no tumor), 1 (tumor up to 0.5 cm), 2 (tumor up to 5 cm), or 3 (tumor >5 cm) is applied to assist in understanding tumor burden. Scores for each of the 12 regions are tabulated to derive the PCI score.

We calculate ascites score in patients with voluminous ascites (FIG 2) based on preoperative imaging. Patient with colorectal primaries and ascites score greater than 3 (or three out of nine abdominal areas with ascitic fluid while on supine position on the CT table) have minimal chances to achieve a complete CRS. In these patients, we start the operation with diagnostic laparoscopy to establish resectability.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Preoperative Planning

Preoperative assessment includes a history and physical, laboratory evaluation consisting of blood counts, comprehensive metabolic panel, CEA, and a blood type with crossmatch of four units of packed red blood cells.

Splenectomy vaccines are routinely administered at least 2 weeks prior to the operation when splenectomy is anticipated.

At the surgeon’s discretion, ureteral stents may be placed prior to incision. This is generally appropriate for patients with a good possibility of ureteral involvement, prior retroperitoneal surgical exploration, or large volume of disease.

A bowel preparation is routine. Patients with a bowel obstruction may benefit from the use of enemas.

Prophylactic antibiotics are administered prior to induction of anesthesia.

Both mechanical and pharmacologic deep vein thrombosis (DVT) prophylaxis is instituted as appropriate.

Positioning and Team Setup

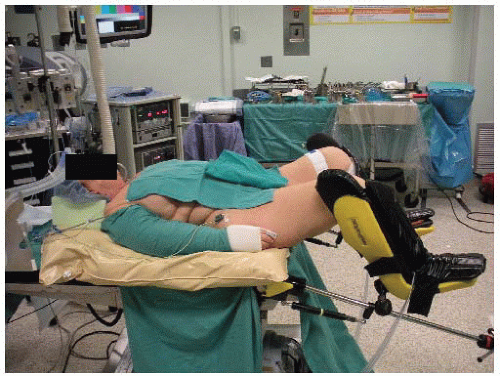

The majority of patients are placed supine. In cases of rectal cancer, induced PSD at modified lithotomy position is preferred (FIG 3).

In the modified lithotomy position, the legs are placed in Allen or Yellofin stirrups. All pressure points are padded to prevent neurovascular injuries and/or calf myonecrosis.

The thighs are positioned level with the abdomen, as this allows placement of a self-retaining retractor without creating excessive pressure between the retractor and the patient’s thighs.

The perineum is positioned flush with the edge of the operating room table.

The arms are placed in a neutral position and supported with suitable armrests.

The surgeon starts at the patient’s right side, with the assistant standing to the patient’s left side and with the scrub nurse standing to the surgeon’s right side (FIG 4). If the patient is in a modified lithotomy position, a second assistant would be standing in between the patient’s legs.

TECHNIQUES

CYTOREDUCTIVE SURGERY

After prepping and draping the abdomen, an incision is made from the xiphoid to the pubis to facilitate complete exposure of the peritoneal cavity.

If the falciform ligament is present, it is resected in continuity with the round ligament prior to placing a fixed retractor (Bookwalter or bilateral Thompson).

All adhesions from previous operations are lysed to allow all areas of the peritoneal cavity to be exposed to HIPEC.

It is important at this point to proceed with a detailed mapping of the distribution of disease prior to commencing with any organ resection. Invasion of major vascular retroperitoneal structure or disease at the porta hepatis should not be undertaken for colon cancer-induced PSD.

CRS is then undertaken to remove all visible tumor deposits if possible. Only peritoneal surfaces involved by tumor deposits are stripped from the abdominal wall using electrocautery.

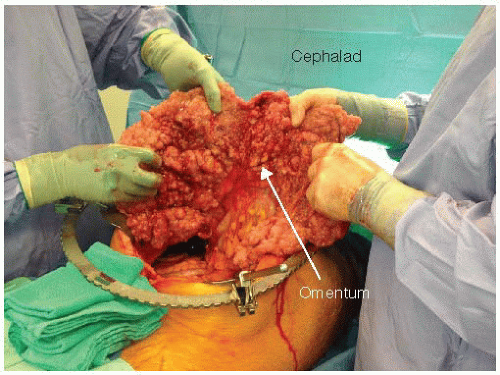

The greater omentum is routinely removed as it is nearly always a site of tumor deposits in patients with carcinomatosis (FIG 5). Any other involved tissue or organ not vital to the patient is also removed. During resection of the lesser omentum (if there is no gross involvement), we

attempt to preserve the vagal branches going to the stomach. This will spare the patient a long-lasting gastroparesis and will significantly improve postoperative quality of life.

FIG 5 • Intraoperative photograph of a patient with peritoneal carcinomatosis. Thickening of the omentum from tumor implants is referred to as “omental cake.”

Splenectomy is performed in case of direct involvement or any identified involvement of the left hemidiaphragm in order to facilitate a complete diaphragmatic stripping. Attention should be taken to avoid injury to the tail of the pancreas. In case of a distal pancreatectomy, a drain should be left in place. Even though the incidence of pancreatic leak is not higher with CRS/HIPEC, the associated mortality is significantly higher and should be taken into consideration.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree