Cutaneous Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphomas

Alejandro A. Gru

DEFINITION

The WHO defines diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type (DLBCL-LT), as a malignant neoplasm of intermediate aggressive behavior, occurring most frequently in the legs of elderly individuals,1 characterized by sheets of large cells in the dermis.2 It is noteworthy that most primary cutaneous DLBCL (PCDLBCL) and secondary forms of systemic lymphomas with cutaneous dissemination shared similar clinicopathologic and immunophenotypic features.3,4,5

EPIDEMIOLOGY

ETIOLOGY

The mechanisms that drive the lymphomagenesis of DLBCL-LT are not understood. However, recent genetic and molecular analysis performed in these groups has revealed a common genetic origin with its nodal counterpart.9 Rare cases with infection of HHV-6 and HHV-8 have been reported.10 More recently, cases of DLBCL presenting in and outside the skin have been found in association with the use of methotrexate (MTX).11,12,13,14,15,16 It appears that some or most of these are associated with Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) infection. Interestingly, the fact that many of these large proliferations of cells regress upon discontinuation of MTX has led to the hypothesis that perhaps some of these should be separated as MTX-related B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders. These subjects also present at a mean age of 76, and the time interval between the use of MTX and the development of the lesions is ∼4 years. Another possible etiologic entity to be considered among DLBCL includes the so-called EBV+ mucocutaneous ulcer. EBV+ mucocutaneous ulcer is a recently described B-cell lymphoproliferative disease that manifests with isolated sharply demarcated ulceration most commonly in the oropharynx, skin, and gastrointestinal tract. A third of the affected patients have a drug-related immunosuppression, but age-related immune suppression is also a common feature.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION/PROGNOSIS

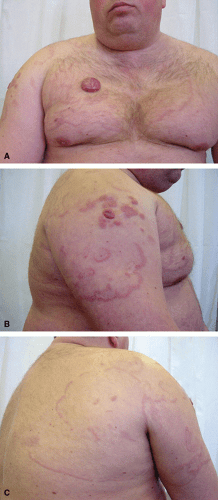

The series from Grange et al.6 showed that the most common clinical features include cutaneous nodules or tumors, deeply infiltrated plaques, large subcutaneous tumors, and more infrequently leg ulcers17 (Fig. 28-1). However, in 10% to 20% of cases, other parts of the body are affected.6,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25 About 13.3% have lesions on the trunk, 15.0% have lesions on the arm, 18.3% on the head, and 71.7% on the leg. The lesions can be unifocal in one-third of cases, but more than one lesion is seen in the majority of cases, and approximately another third of cases have more than five lesions clinically. Large ulcerations with infiltrative borders have led to the misdiagnosis of chronic venous ulcers and stasis.26 Upon recurrence or in the evolution of the disease, the clinical lesions usually retain the tropism for the legs. A single case of isolated relapse in the lungs has been reported.27 During the early phases, the lesions can have an annular configuration and might resemble erythema chronicum migrans or gyrate erythemas.28,29 Other uncommon clinical presentations have included garland-like lesions on the chest30 (Fig. 28-2), telangiectatic lesions31 (Fig. 28-3), postexcision from Jessner-like infiltrate on the shoulder,11 postradiation,32 postburn,33 dermatomyositis-like,34 multiple nodules in the leg with a lymphangitic pattern (mimicking infection from Sporotrichosis),35 chronic lymphedema-like,36 mononeuritis multiplex,37 bluish–reddish multicolored rainbow pattern,38 and a solitary nodule in the breast.39 Rarely cases might not be palpable clinically, and can present as fever of unknown origin.40 The presence of B symptoms is seen in 10% of cases and nearly 12% have elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels in the blood. Rare cases have been reported to show spontaneous resolution without treatment,41 POEMS-like syndrome,42 and in association with hemophagocytic syndrome.43 DLBCL-LT can also occur in association with HIV infection,44 renal transplant recipients,45,46 and can be associated with intravascular cryoglobulin deposits.47 A case revealing dissemination to the paranasal sinuses has also been reported.48

FIGURE 28-1. PCDLBCL-LT. A and B. Clinically, the lesions consist of solitary nodules in the legs with a purple color and more frequently do not reveal ulceration. |

Although, by definition, these lymphomas are limited to the skin at presentation, they often spread to extracutaneous sites, most commonly to the lymph nodes, the bone marrow, bone,49 the central nervous system,6,19,50,51,52,53 and other organs (e.g., eye,53 ureters54). Sentinel lymph node biopsy has been advocated in some circumstances to distinguish a primary cutaneous lymphoma from a secondary cutaneous dissemination of a systemic lymphoma.55

In contrast to other cutaneous B-cell lymphomas (CBCLs), the prognosis of DLBCL-LT is poor with a 5-year survival rate of 55% (20% to 60%).56,57,58 Zinzani et al.19 have reported a survival of 73% in 51 patients from Italy. A more recent study from Grange et al.50 in France (n = 115) has shown an increased survival from 55% to 74% and 46% to 66% at 3 and 5 years, respectively. The appearance of multiple tumors, the location on both legs (involvement of one leg vs. both legs: 5-year survival rate 45% vs. 36%), the loss of expression of p16 (p16 negative vs. positive: 5-year survival rate 43% vs. 70%), and activated apoptosis cascade are prognostically unfavorable prognostic markers.59 Sex, B symptoms, BCL-2 expression, MUM-1 expression, performance status, serum LDH level, duration of lesions before diagnosis, and variables related to therapy have no effect on survival.6 Multivariate analyses have identified location on the legs and multifocality as independent markers for prognosis.

TREATMENT

The study from Grange et al. in France has shown an improvement in survival rates in mainly two groups of patients: (1) treated from 1988 to 2003 and (2) treated from 2004 to 2010. The main differences in the groups evoke a change from a pure treatment with radiation (earlier on the first group)6,60,61 to a rituximab-based regimen containing polychemotherapy.62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71 During 2002 to 2005, it was demonstrated that addition of rituximab to CHOP regimen improved response rates, short-term survival, and long-term outcome without increasing toxic effects in patients aged 60 to 80 years with DLBCL. Many difficulties often encountered with these patients are related to the presence of other diseases, diminished organ function, and altered drug metabolism. In day-to-day practice, this resulted in frequent replacement of the standard rituximab–CHOP regimen with rituximab regimens including lower doses (rituximab–mini-CHOP) or no anthracycline. Recent alternatives to mini-CHOP regimens include rituximab plus pegylated doxorubicin, with preliminary good results in individuals who are less likely to benefit from a more aggressive chemotherapeutic regimen.72 Single-agent rituximab has also been used for palliative care.73 A study from Hamilton et al.74 showed (on a CHOP-based regimen) that nearly 50% or more of the patients in their series (n = 25) received adjuvant radiation treatment. Limb perfusion using Melphalan has been used in an isolated case report with good clinical response.75 Yttrium-90 ibritumomab tiuxetan radioimmunotherapy has been used post-rituximab in a series of 10 patients, most of whom had relapsed DLBCL-LT.76 Lenalidomide monotherapy has also been used with some success in relapsed cases.77 A recent phase II clinical trial of interferon-γ gene transfer with TG1042 showed local responses in the two cases of CBCL examined (one disseminated primary cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma (PCMZL) and one PCDLBCL-LT), lending support for further developing this novel interferon-γ gene transfer in CBCL.78

HISTOLOGY

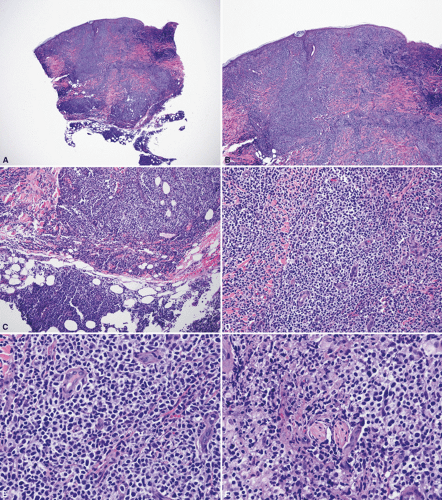

The typical histologic features of DLBCL-LT show a diffuse infiltrate in the entire dermis, often extending into the subcutaneous tissue (Fig. 28-4). Plaza et al.79 published a large series of 79 cases of DLBCL: in their series they found 11.4% of cases with a sclerosing pattern with thickened interconnective bands of connective tissue in the dermis, surrounded by groups of large lymphoid cells, admixed with smaller cells. A similar proportion of cases show large areas of geographic necrosis (en-masse necrosis). More uncommon patterns represented in their series included anaplastic morphology (Figs. 28-5 and 28-6) (7.6%), angioinvasion (7.6%), a starry-sky pattern (mimicking Burkitt or Burkitt-like lymphomas, 6.3%), admixed inflammation (6.3%), spindle cells (6.3%), a histiocytoid appearance (5.1%), pseudosarcomatous areas (3.8%), multilobated cells (3.8%), and epidermotropism (2.5%). The presence of epidermotropic cells can sometimes include the presence of Darier nests (Pautrier microabscesses). Rare cases can also show a band-like infiltrate that could potentially mimic mycosis fungoides. Cytologically, the neoplastic cells consist predominantly of large cells with round nuclei and variable prominent nucleoli. The so-called spindle-cell pattern80,81,82,83,84 has been favored by some authors to represent variants of primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma (PCFCL) with diffuse areas. Some cases can also relapse with an intravascular component, which can potentially mimic intravascular large B-cell lymphoma.85 The presence of starry-sky areas should also raise the consideration of cutaneous involvement by Burkitt lymphoma, or involvement by B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable, with intermediate features between DLBCL and Burkitt lymphoma.86 Both of these lymphomas usually show an extraordinarily high proliferation index. In cases of DLBCL-LT exhibiting a significant reactive T-cell infiltrate, occasional epithelioid granulomas (histiocytic cells) can be found, reflecting a local paraneoplastic granulomatous diathesis.79 In their series, cutaneous perineural invasion was a relatively infrequent phenomenon, but in our experience, this appears to be more common than what has been reported.

IMMUNOPHENOTYPE

In addition to traditional B-cell markers (CD19, CD20, CD22, CD79a, PAX-5), PCDLBCL-LT classically expresses BCL-2, IRF4/MUM-1, and FOXP187 (Fig. 28-7). However, this immunophenotype is not specific to PCDLBCL-LT and may also be seen in other DLBCLs that secondarily involve the skin. Follicular dendritic networks are typically lacking on PCDLBCL-LT; however, Plaza et al.88 have shown that in nearly 12.5% of cases focal dendritic networks can be seen using CD21 or CD35 immunostains. The importance of using MUM1 and BCL-2 in the diagnosis of this disease has entered into debate, as the WHO describes that in nearly 10% of cases those markers can be absent.1 The study from Plaza et al.88 has shown that MUM1 was present in only 60% of PCDBCL-LT. Some authors have advocated the use of PCDBCL, not otherwise specified (PCDBCL-NOS) for those cases which lack BCL-2 and MUM1.18,59 Others have shown a lack of prognostic significance upon the expression of those markers6,18,89 when the clinical and histologic diagnosis otherwise fits the criteria for PCDLBCL-LT. Most cases show weak expression of BCL-6, but lack of CD10. IgM expression with or without IgD coexpression (only 50%) is strongly expressed in PCDBCL-LT and the staining could have a potential role to distinguish it from PCFCL.90 Expression of CD30 can also occur in some cases.91,92 Similar nodal counterparts are classified as “anaplastic variants”.93 A better behavior of cases expressing CD30 has been seen in nodal cases, but data from PCDLBCL-LT are still missing.94,95 Expression of MYC is seen in more than 55% of cases.9 PD-1 expression is very rarely seen in LT lymphoma. However, PD-1 can be seen with certain frequency in T cells in the background of PCFCL. Therefore, PD-1 might be another putative marker that can help discriminating between the two entities.96 EBV positivity has been rarely described.97 The FOXP1 overexpression can be related to numerical gains of the gene, but not to translocations.98 The presence of FOXP3 expression and abundance of T-cell regulatory cells have been linked to a better prognosis.99 MUM1 expression is not linked to an IRF4 rearrangement.100 OCT-2 expression (more frequently seen in PCDLBCL-LT) can help distinguish this from PCFCL. Novel markers such as TCL-1 and BLIMP1 have been reported in PCDLBCL-LT.101

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree