Overview

In Chapter 9, I discussed the tragic collision of two 747s on a foggy morning in Tenerife, the crash that vividly illustrated to everyone in the field of commercial aviation the risks associated with steep and unyielding authority gradients. In response to Tenerife and similar accidents, aviation began a series of training programs, generally called “crew resource management” or “cockpit resource management” (CRM) programs, designed to train diverse crews in communication and teamwork. Some of these programs also incorporate communication skills, such as training in Situation, Background, Assessment, and Recommendations (SBAR) and briefing/debriefing techniques (Chapter 9). There is widespread agreement that these programs helped transform the culture of aviation, a transformation that was largely responsible for the remarkable safety record of commercial airlines over the past generation (Figure 9-1).

As the healthcare field began to tackle patient safety, it naturally looked to other organizations that seemed to have addressed their error problems effectively.1 The concept of high reliability organizations (HROs) became shorthand for the relatively mistake-free state enjoyed by airlines, computer chip manufacturers, nuclear power plants, and naval aircraft carriers—but certainly not healthcare organizations.2,3 According to Weick and Sutcliffe, HROs share the following characteristics:2

- Preoccupation with failure: the acknowledgment of the high-risk, error-prone nature of an organization’s activities and the determination to achieve consistently safe operations.

- Commitment to resilience: the development of capacities to detect unexpected threats and contain them before they cause harm, or to recover from them when they do occur.

- Sensitivity to operations: an attentiveness to the issues facing workers at the frontline, both when analyzing mistakes and in making decisions about how to do the work. Management units at the frontline are given some autonomy in identifying and responding to threats, rather than being forced to work under a rigid top-down approach.

- A culture of safety: in which individuals feel comfortable drawing attention to potential hazards or actual failures without fear of censure from management.

Over the past few years, the patient safety world has embraced the concept of HROs. Personally, I find the concept intriguing, but wonder whether it is something of a healthcare “MacGuffin.” Legendary film director Alfred Hitchcock used to love to insert a MacGuffin—a plot device, such as a piece of jewelry, a stack of important-looking papers, or a suitcase, that “motivates the characters or advances the story, but the details of which are of little or no importance otherwise”—into his films. Similarly, when I hear a healthcare organization pledge to become an HRO, I wonder whether they are trying to advance their own “patient safety story” without committing themselves to an actionable or measurable target. In this, I find myself agreeing with British safety expert Charles Vincent, who wrote, “Put simply, reading the HRO literature offers a great deal of inspiration, but little idea of what to do in practice to enhance safety.”4,5

This hints at an overarching challenge we face as we enter the crucial but hazy world of safety culture, which can sometimes feel like the weather—everybody talks about it but nobody does anything about it. When it comes to safety culture, everyone seems to have an opinion. As with many complex matters in life, the truth lies somewhere between the commonly polarized viewpoints. Is a safe culture top down or bottom up? Both. Is it “no blame” or dependent on a strong framework for accountability? Both. Is it a local phenomenon (“microculture”) or an attribute of an entire organization? Both. Is it enhanced by following a set of rules and standards or by creating a nimble frontline staff, able to innovate, think on its feet, and even break a rule or two when that’s required for safe care? Well, both.

The gossamer nature of safety culture—sometimes defined as “the way we do things around here”—can be frustrating to those entering the field, whether their goal is to improve the safety of their own practice or that of an entire hospital. It seems to be nowhere and everywhere. Yet the past few years have seen real progress in the area of safety culture: our understanding of what it means is growing richer and more nuanced, and we are discovering robust ways of measuring it and, to a degree, improving it. This, thankfully, provides something for even the pragmatist to grab on to.

An Illustrative Case

In a large teaching hospital, an elderly woman (“Joan Morris”*) is waiting to be discharged after a successful neurosurgical procedure. A floor away, another woman with a similar last name (“Jane Morrison”) is scheduled to receive the day’s first cardiac electrophysiology study (EPS), a procedure in which a catheter is threaded into the heart to start and stop the heart repetitively to find the cause of a potentially fatal rhythm disturbance. The EPS laboratory calls the floor to send “Morrison” down, but the clerk hears “Morris” and tells that patient’s nurse that the EP lab is ready for her patient. That’s funny, she thinks, my patient was here for a neurosurgical procedure. Well, she assumes, one of the docs must have ordered the test and not told me. So she sends the patient down.

Later that morning, the neurosurgery resident enters Joan Morris’s room to discharge his patient, and is shocked to learn that his patient is in the EPS laboratory. He sprints there, only to be told by the cardiologists that they are in the middle of a difficult part of the procedure and can’t listen to his concerns. Assuming that his attending physician ordered the test without telling him, he returns to his work.

Luckily, the procedure, which was finally aborted when the neurosurgery attending came to discharge his patient and learned she was in the EPS laboratory, caused no lasting harm (in fact, the patient later remarked, “I’m glad my heart checked out OK”).6

The case illustrates several process problems, and it would be easy, even natural, to focus on them. Many hospitals would respond to such a case by mandating that procedural units use complete patient names, hospital numbers, and birthdays when calling for a patient; by requiring a written order from the physician before allowing his or her patient to leave a floor for a procedure; by directing that important information be read back to ensure accuracy; or by implementing a bar coding system that matches a patient’s identity with the name in the computerized scheduling system. And these would all be good things to do.

But these changes would leave an important layer of Swiss cheese (Chapter 1)—perhaps the most crucial one of all—unaddressed, the one related to the cultural issues that influence, perhaps even determine, the actions of many of the participants. A closer look at the case, now through a safety culture lens, reveals issues surrounding hierarchies, the “culture of low expectations,” production pressures, and rules.6 After a brief discussion about measuring safety culture, I’ll address each of these topics in turn, and then consider solutions such as teamwork training and checklists. Rapid Response Teams and dealing with disruptive behavior are covered in Chapters 16 and 19, respectively.

Measuring Safety Culture

While one could try to assess safety culture by directly observing provider behavior (and some studies do just that7,8), the usual method is through self-reports of caregivers and managers, collected via a survey instrument. The two most popular instruments are the AHRQ Patient Safety Culture Survey and the Safety Attitudes Questionnaire (SAQ).9–11 A core benefit of using one of these validated instruments is that they have been administered to tens of thousands of healthcare workers and leaders, which means that benchmarks (for various types of clinical units and healthcare organizations) have been established. There has also been considerable research performed using these instruments, with results that have been surprising, sometimes even eye-popping. They include:

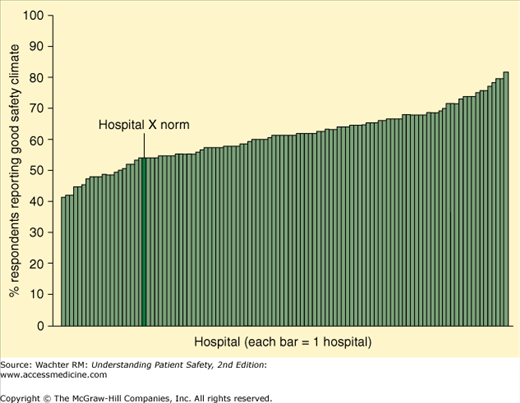

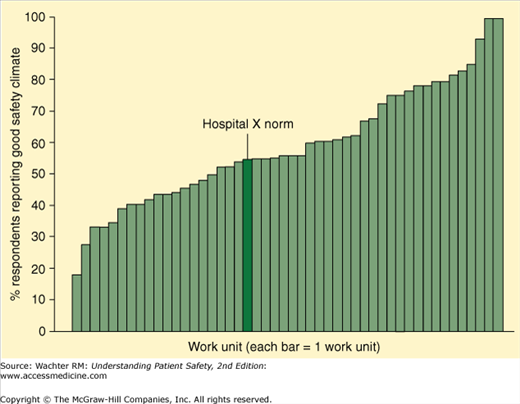

- Safety culture is mostly a local phenomenon. Pronovost and Sexton administered the SAQ to clinicians at 100 hospitals.12 While they found considerable variation in safety culture across hospitals (with positive scores ranging from 40% to 80%, Figure 15-1), there was even more variation when they looked at 49 individual units within a single hospital (positive scores ranging from 0% to 100%, Figure 15-2). It is not too much of an oversimplification to say that your hospital doesn’t have a safety culture—rather, your fourth floor ICU has one, your step-down unit 50 ft away has a different one, and your emergency department has still another one. This is liberating in a way, since one need not look far afield for the secrets of a strong safety culture—it’s likely that some unit in your organization has already figured them out.

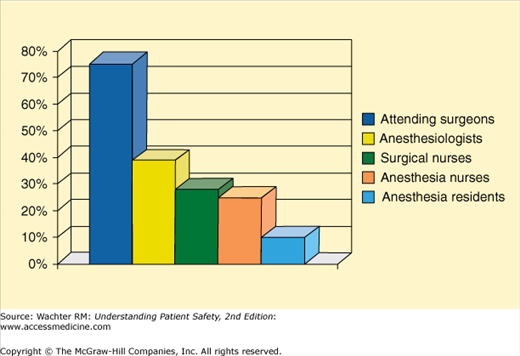

- Safety culture varies markedly among different providers, and it is important to query all of them to paint a complete picture of a unit’s culture. In a seminal 2000 study, Sexton et al. administered the SAQ to members of operating room teams (Figure 15-3).13 Whereas nearly 80% of the surgeons felt that teamwork was strong in their OR, only one in four nurses and 10% of the residents felt the same way. More recent studies have found that these differences persist.14,15

- Safety culture is perceived differently by caregivers and administrators. Singer et al. found that problematic views of culture were much more common among frontline providers than hospital managers working in the same facilities.16 They argue that this difference may be an important determinant of an organization’s safety: if frontline workers perceive poor safety culture but the leaders remain blissfully unaware, the two groups are unlikely to be able to make appropriate decisions regarding how to prioritize safety concerns. Interestingly, another study by the same group found that there were differences even among managers, with senior managers having rosier views of culture than lower-level administrators.17

There is increasingly powerful evidence that safety culture scores correlate with clinical outcomes, including infection and readmission rates.10,18–21 The Joint Commission now requires that accredited organizations administer and analyze safety culture surveys each year, and doing so is one of the National Quality Forum’s “safe practices” (Appendix VII). Of course, simply measuring safety culture without a strategy to improve it will be of limited value.

Hierarchies, Speaking Up, and the Culture of Low Expectations

In Chapter 9, I introduced the topic of authority gradients—the psychological distance between a worker and his or her supervisor. These gradients are often referred to in terms of hierarchies; an organization is said to have steep hierarchies if these gradients tend to be large. In the wrong patient case described at the start of this chapter, the nurse’s reluctance to raise concerns when told that her patient was being called for a procedure she didn’t know about, or the neurosurgery resident’s decision to acquiesce after getting pushback from the cardiology staff, can be attributed at least partly to steep authority gradients. So too can the tragic events that doomed the KLM 747 in Tenerife (Chapter 9). You may also recall the case that begins Chapter 9, in which a Code Blue is aborted when a physician finds a “no code” order in the wrong patient’s chart. There too, a young nurse was reluctant to question the resident’s confident proclamation, even though she had received sign-out an hour earlier that portrayed the patient’s status as “full code.”

Authority gradients are natural and, to a degree, healthy. But when they prevent caregivers with important knowledge or concerns from sharing them with superiors for fear of being wrong or angering the boss, they become dangerous. This issue pertains not only to direct clinical care but also to whether the ward clerk, pharmacist, or intern will point out hazardous conditions to his or her floor manager, pharmacy director, or department chair. Safe organizations find ways to tamp down hierarchies at all levels, encouraging individuals (including patients, Chapter 21) to speak up when they see unsafe conditions or suspect that something might be awry.

In their masterful discussion of the wrong patient case in our Quality Grand Rounds series in the Annals of Internal Medicine (Appendix I), Chassin and Becher introduced the concept of “the culture of low expectations.”6 In reflecting on the actions—or inactions—of the nurse and the resident, they wrote:

We suspect that these physicians and nurses had become accustomed to poor communication and teamwork. A ‘culture of low expectations’ developed in which participants came to expect a norm of faulty and incomplete exchange of information [which led them to conclude] that these red flags signified not unusual, worrisome harbingers but rather mundane repetitions of the poor communication to which they had become inured.6

Fighting the culture of low expectations is a crucial step in creating a safety culture. Doing this requires a change in default setting of all the providers, from:

If you’re not sure it is wrong, assume it is right (it’s probably just another glitch, we have them all the time around here)

to

If you’re not sure it is right, assume that it is wrong—and do whatever it takes to become sure, even at the cost of delaying the first case in the operating room or making someone important a little irritated.

There is no shortcut to fighting the culture of low expectations. Yes, it is important to clean up communications with tools such as SBAR (Chapter 9) and information technology (Chapter 13)—making the instinct to think, “another glitch, but it must be right,” less automatic. (I often tell healthcare leaders that they can improve their organization’s safety immediately by simply purging the four words—it must be right—from their staff’s vocabulary.)

But healthcare organizations will always have examples of faulty, ambiguous communication or rapid changes that cannot be communicated to everyone. Therefore, changing the dominant mindset from “A” to “B” requires a powerful and consistent message from senior leadership (Chapter 22). As importantly, when a worker does take the time to perform a double check after noticing something that seems amiss—and it turns out that everything was okay—it is vital for senior leaders to vocally and publicly support that person. If praise is reserved for the “great save” but withheld for the clerk who voiced a concern when nothing later proved to be wrong, staff are unlikely to adopt mindset “B,” because they will still fret about the repercussions of being mistaken.22

Production Pressures

Another, perhaps more subtle, culprit in the EPS case—and in safety culture more generally—is production pressure.23,24 In a nutshell, every industry, whether it produces hip replacements or SUVs, has to deal with the tension between safety and throughput. The issue is not whether they experience this tension—that would be like asking if they experience the Laws of Gravity. Rather, it is how they balance these twin demands.

When my children were small, we often went to a well-known pancake restaurant on weekend mornings for breakfast. I was in awe of the establishment’s speed: customers were seated promptly, their orders were taken rapidly, putting a fork down on a cleaned plate immediately cued the server to politely ask “is there anything else I can get you today?,” and the cleanup was brisk. The reason for this pace is obvious: in the fast food business, with large boluses of customers arriving en masse and relatively low profit margins per customer, corporate survival depends on throughput. The food is fine but not great, and there are periodic errors (of the two-forks, no-knife type). But that’s what happens when production trumps safety and reliability.

Only a couple of miles from this particular restaurant is San Francisco International Airport (SFO). The tension between production and safety is particularly acute at SFO, since its two main runways are merely 738 ft apart—I often feel like I can read the newspaper headlines of a passenger in an adjacent plane when both runways are operating.

The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) enforces inviolable rules about throughput at SFO and every other airport. For example, when the cloud cover falls below 3000 ft (which, in foggy San Francisco, happens often), one of the two runways is closed, gumming up the entire U.S. air traffic control system. And whatever the weather, planes cannot land more often than one each minute. The explanation for these rules is as simple as the explanation for the restaurant’s speed: when the aviation industry has to choose between production and safety, safety wins. The result: despite 400,000 takeoffs and landings each year, there has not been a fatal crash at SFO in over 50 years.

I’ve used this metaphor many times in speeches to hospital staff and leaders, usually capping it by asking audiences: “As it balances production and safety, does your hospital look more like the pancake restaurant or SFO?” Although things have improved a bit in the last few years, the answers still run about 10:1 in favor of the restaurant.

Addressing production pressures sometimes involves creating more efficient processes that free up time to do the work safely (just recall the description in Chapter 13 of the maddening waste of time and effort that often occurs when a nurse has to chart a blood pressure measurement). But it also involves choices, such as slowing down the operating rooms when they reach a state of chaos. This is expensive and disruptive, but so is closing a runway. In aviation, our society willingly pays this price to ensure safety, but we have not done so in healthcare.

As always, it is vital to appreciate the limits of analogies between healthcare and other industries. When SFO closes Runway 10R, planes sit on the ground (or circle overhead) and passengers are inconvenienced. But if we close our emergency department to new ambulances (“go on divert”) because of safety concerns, patients, some quite ill, need to be taken to other facilities. This carries its own safety cost, one that needs to be weighed as we address this challenging balance.

Charles Vincent quotes an oil industry executive who captured the tension beautifully; I think of this statement every time I hear a hospital CEO or board member earnestly declare, “safety is our top priority.” The executive said:

Safety is not our top priority. Our top priority is getting oil out of the ground. However, when safety and productivity conflict, then safety takes priority.4