Consensus

Management consensus

GERD covers a spectrum of clinical disorders resulting from reflux of the gastric contents rostrally. The condition is increasingly common and making progressively increasing demands on the health service budget. The rise of GERD in the developed world over the last 50 years has paralleled the increase in obesity and sedentary behavior of our populations and shows no signs of abating. A rare complication of reflux disease, esophageal adenocarcinoma, is also being diagnosed more frequently and might be the price being paid for the indulgent and inactive lifestyle to which we have become accustomed. There are several contentious areas in the management of GERD, in particular the problems of accurately identifying the most specific symptoms of GERD and the management of patients whose symptoms are not abolished by potent acid-suppression medications. The problem of esophageal and extraesophageal nocturnal symptoms and their relationship to acid secretion, reflux, and impaired clearance of refluxate during the hours of recumbency and sleep are major areas of therapeutic interest.

As a consequence of the atypical manifestations of GERD and the association of Barrett’s esophagus with esophageal adenocarcinoma, more attention has been drawn to GERD recently, which probably contributes in part to its increasing prevalence. Why else might GERD be becoming more prevalent? Is it only due to increased body mass in the developed world, or are our stomachs now producing more acid? Perhaps esophageal mucosal defenses are less adept than they once were?

There is no gold standard in diagnosing and staging GERD. Thus, the choice of a diagnostic strategy is based on symptoms, resources, and the clinical question posed. For example, in patients with alarm symptoms or who are older than 50 years of age, endoscopy is clearly important to identify complications or alternative diagnoses, whereas in patients with suspected extraesophageal manifestations, such as noncardiac chest pain, a 24-hour pH-recording study may be the most appropriate investigation. In many instances (e.g., in younger patients with a short history of typical symptoms), a therapeutic trial of a PPI at a high dose (often termed the PPI test) is sufficient to confirm a clinical diagnosis, especially in primary care. There is no consensus regarding how long this initial trial should be or the dosing strategy after a successful test. In

particular, it is not established that the PPI test has actual cost-saving advantages in practice over a strategy involving early endoscopy in practice, as theoretically predicted from a Markov model.

particular, it is not established that the PPI test has actual cost-saving advantages in practice over a strategy involving early endoscopy in practice, as theoretically predicted from a Markov model.

Definitions and symptoms

Gastroesophageal reflux may produce erosions (erosive GERD), no overt mucosal damage [nonerosive reflux disease (NERD)], or atypical manifestations of reflux, such as pulmonary diseases, noncardiac chest pain, reflux laryngitis, or dental erosions. However, the distinction between NERD and GERD becomes less important as microscopic esophageal damage is increasingly detected by chromoendoscopy and other methods.

The typical symptom of gastroesophageal reflux is usually described as a burning sensation radiating up from the sternum. This is commonly referred to as heartburn in English-speaking countries, but in other languages there is usually no cardiac reference. It is now becoming increasingly apparent that there is a large discrepancy between the intensity of the symptom of heartburn and the amount of acid regurgitation and objective evidence of pathologic gastroesophageal reflux. Indeed, the evidence that most patients treated “effectively” for ulcer healing still remain with a variety of persistent symptoms demonstrates our poor understanding of the cause of many heartburn-like symptoms. Whether these refractory symptoms represent “functional heartburn” or result from reflux of gastric contents is unclear. The recent decisions of British and Canadian gastrointestinal societies to include heartburn in the definition of dyspepsia, unlike that of the Rome II criteria, suggests that the symptom “heartburn” does not travel well across different cultures. This problem is also exemplified by the inability to understand a standard definition of GERD by a group of Scandinavian GERD patients.

Issues related to definitions of heartburn are likely to cloud clinical trials of therapy for GERD, particularly NERD, in which symptom relief is the main outcome measure. Development of an instrument that accurately evaluates specific esophageal and extraesophageal symptoms and that can be used to assess their prevalence and severity in studies of populations and in clinical trials is needed. GERD and NERD symptomatology might be best characterized by a multidimensional construct that would allow for a comprehensive assessment of the full gamut of symptoms, including the ability to document symptoms longitudinally, considering also external factors. Self-administered diaries that allow the patient to assess symptoms at multiple time points may provide the valid, reliable, responsive scale for the assessment of GERD symptom dimensions during therapy that is currently lacking.

Pathophysiology

There have been relatively few recent insights into the increasing prevalence or pathophysiology of GERD. An increased frequency of TLESRs is a well-recognized feature of GERD, and the recent demonstration that TLESRs may increase in the presence of a coexisting hiatal hernia may explain the association of hiatal hernia with GERD. More recently described phenomena include

a more distensible gastroesophageal junction in GERD patients with hernias and the presence of a “pocket” of gastric juice in the gastric fundus that is much more highly acidic than the general gastric contents, which, therefore, may be particularly damaging to the mucosa at the gastroesophageal junction.

a more distensible gastroesophageal junction in GERD patients with hernias and the presence of a “pocket” of gastric juice in the gastric fundus that is much more highly acidic than the general gastric contents, which, therefore, may be particularly damaging to the mucosa at the gastroesophageal junction.

There are many known inhibitors of TLESR, including CCK antagonists, nitric oxide antagonists, atropine, morphine, cannabinoids, baclofen, and tegaserod; the newer members of this growing family of drugs are being actively investigated for their possible efficacy in primary or adjunctive therapy. However, the clinical usefulness of agents that promote LES contraction and the relative contribution of a low LES pressure to the pathogenesis of GERD remain uncertain in the absence of a clean pharmacologic agent whose actions are confined to this site. Similarly, although duodenal contents and pepsin are established injurious agents for the esophageal mucosa, the efficacy of potent acid suppression has drawn attention away from other toxic agents in gastric contents.

Barrett’s esophagus

The metaplastic response of the esophageal mucosa to chronic damage, known commonly as Barrett’s esophagus, is the subject of considerable current attention owing to its malignant potential. With the steady and inexorable rise in esophageal adenocarcinoma among white males in the developed world, it is important to understand the determinants responsible for the progression to and from Barrett’s esophagus. Controversy surrounds almost every aspect of Barrett’s esophagus—its true population prevalence, its relative contribution to the development of adenocarcinoma, and the rate of progression from Barrett’s to dysplasia and cancer. Whether there are any strategies that may reduce this risk of progression and whether endoscopic surveillance is of any benefit in detecting lesions at an early enough stage to alter the natural history of adenocarcinoma are also unknown.

It is uniformly accepted that a critical issue in the management of GERD is the need to ensure appropriate effective therapy to minimize the risk of the development of Barrett’s esophagus and to identify it accurately. Patients found to have Barrett’s esophagus at biopsy but with no dysplasia should be placed in a surveillance program with approximately 5-year intervals between surveillance endoscopies. This opinion is to a large extent based on cost-effec-tiveness analysis data and may need to be modified with the significant alterations in endoscopic charges. If the pathologist diagnoses Barrett’s esophagus and identifies the presence of dysplasia, then the material should be reviewed by two expert independent pathologists to confirm the diagnosis and to establish whether the changes conform to a pattern consistent with low- or high-grade dysplasia. The identification of low-grade dysplasia mandates repeat biopsy at 1 year to determine whether there is progression to high-grade dysplasia. If at the 1-year time point multiple biopsies fail to identify evidence of dysplasia, the patient should return to the normal surveillance program; if low-grade dysplasia persists, then endoscopy and biopsy should again be repeated in 1 year. If there is a diagnosis of high-grade dysplasia at the initial or any follow-up biopsy, then the patient should be treated with a high-dose

PPI for 3 months to rule out the possibility of inflammatory pseudodysplasia. If the repeat biopsy after 3 months confirms high-grade dysplasia, then the patient should be referred for consideration of surgery or ablative therapy. Some experts have expressed the opinion that very carefully repeated endoscopic surveillance of high-grade dysplasia can be performed to monitor for and biopsy any visible mucosal abnormality. Under such circumstances, surgery might be obviated until a carcinoma is discovered. However, the majority of authorities in this field are uncomfortable with this approach and express a preference for prophylactic surgery once the presence of a high-grade lesion had been reliably identified, provided the risk of surgery in a particular patient does not exceed that of the disease. Ablation therapy by laser, bicap, heater probe, or photodynamic therapy for Barrett’s esophagus, dysplasia, or both, should be currently regarded as experimental.

PPI for 3 months to rule out the possibility of inflammatory pseudodysplasia. If the repeat biopsy after 3 months confirms high-grade dysplasia, then the patient should be referred for consideration of surgery or ablative therapy. Some experts have expressed the opinion that very carefully repeated endoscopic surveillance of high-grade dysplasia can be performed to monitor for and biopsy any visible mucosal abnormality. Under such circumstances, surgery might be obviated until a carcinoma is discovered. However, the majority of authorities in this field are uncomfortable with this approach and express a preference for prophylactic surgery once the presence of a high-grade lesion had been reliably identified, provided the risk of surgery in a particular patient does not exceed that of the disease. Ablation therapy by laser, bicap, heater probe, or photodynamic therapy for Barrett’s esophagus, dysplasia, or both, should be currently regarded as experimental.

In patients being endoscoped for any reason other than GERD, Barrett’s esophagus may be much more prevalent than was previously thought (occurring in at least 10% of patients biopsied during diagnostic endoscopy). However, community-based studies are needed to define the age, sex, and race-related prevalences and other clinical features that may influence the risk of developing this lesion. Estimates of progression from Barrett’s esophagus to adenocarcinoma of the esophagus in GERD patients have recently been downgraded to approximately 0.5% per year, but this figure may still be an overestimate, because most esophageal adenocarcinomas present de novo in patients without a prior diagnosis of Barrett’s esophagus, and in some patients, Barrett’s is not apparent at the time when the cancer presents.

Although there is little consensus regarding the merits of population screening to detect Barrett’s, the practice in most developed countries is to survey GERD patients with Barrett’s esophagus at intervals of 1 to 5 years, based on the hope that this will allow the detection of early cancers and thereby alter the natural history of the disease. How do we identify the small subset of Barrett’s patients who may really benefit from surveillance? Studies currently in progress are likely in the near future to identify genetic markers in initial screening biopsies that will select from a large number of patients with Barrett’s the small subset at increased risk of progressing to cancer, thus justifying costly continued surveillance in this small subset.

In the absence of such information, physicians may feel under some pressure to treat patients with Barrett’s metaplasia empirically with acid-suppression medications. These forces derive from small studies demonstrating a potential normalization of surrogate endpoints, such as proliferation. Although the positive studies supporting such a policy are often emphasized, similarly designed studies that demonstrate no effect of these interventions on proliferation and other markers (including endoscopic and histologic factors) have frequently been ignored. Well-conducted, large prospective studies using as endpoints the progression of intestinal metaplasia to dysplasia or cancer are needed to definitively address whether acid inhibition, anti-cox drugs, or other potential chemopreventive interventions are of clinical value. Hopefully, in the future, there will be risk-stratified individualized approaches to screening, entry into surveillance programs, and possibly even treatment based on the demographic profile of the patient or on molecular markers in the at-risk mucosa as well as

at the genomic level. These markers may also include real-time indicators of the state of the esophageal mucosa using, for example, optical coherence tomography, magnification, and chromoendoscopy.

at the genomic level. These markers may also include real-time indicators of the state of the esophageal mucosa using, for example, optical coherence tomography, magnification, and chromoendoscopy.

Medical therapy

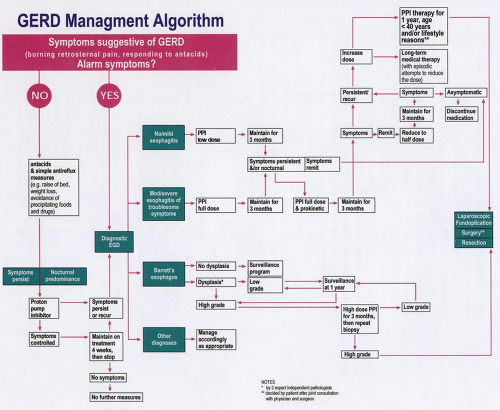

Most patients with GERD present to and are managed by general practitioners; some of the care for patients with GERD will require referral to a gastroenterologist and a surgeon. The management of GERD is a continuum, with management based on not only symptoms, but also on referral patterns and, more increasingly, financial constraints. The first step in the management of the patient with suspected GERD is a history and physical examination. A history of retrosternal burning-type chest pain radiating up from the epigastrium toward the throat is characteristic of GERD, and such symptoms have a high specificity for the diagnosis. If the patient has either atypical symptoms or any alarm symptoms such as dysphagia, anemia, weight loss, predominantly abdominal pain, or pain that does not respond to antacids or first develops symptoms after the age of 50 years, then prompt referral for endoscopy is necessary.

The majority of patients probably do not require endoscopy initially, and such patients should be counseled in regard to simpler antireflux measures, which may include elevation of the head of the bed, weight loss, and the avoidance of precipitating foods and drugs. It is of note, however, that there exist few rigorous data to support the concept that such measures are either of proven or longterm benefit in the management of GERD. The patient should also be advised to take antacids at the time of symptoms and to avoid heavy meals late at night or within 3 hours of retiring to bed. If symptoms persist after 2 to 4 weeks of these simple measures, or if antacids are needed often, if not daily, then formal therapy should be instituted. In the past, the first line of treatment was considered to be the use of an H2 receptor antagonist, but the current, almost uniform, positive clinical experience with the use of PPIs at the standard (low) dose as initial therapy suggests that this strategy is more acceptable to both clinicians and patients. In circumstances in which the pain is a consistent component of the symptomatology, and particularly if there is a nocturnal component, the use of a PPI should be given unequivocal consideration.

If the symptoms are more suggestive of a motility problem, or it is felt that evidence of a motility component to the presentation is evident, a prokinetic drug, such as the 5-HT4 receptor agonist cisapride, may be considered. Such agents (motility) are, however, nonspecific in their site of gastrointestinal action and often display considerable adverse effects. These drugs should be given initially as a 1-month trial and then discontinued. If symptoms recur after this 4-week trial, or if they are not relieved during this treatment period, then the patient should be referred for endoscopy. Although the decision to undertake endoscopy at this time is somewhat arbitrary, it is consistent with the widely accepted position that a “once-in-a-lifetime endoscopy” in reflux disease is acceptable. Thus, an endoscopic evaluation can be included in the database of the patient before major and (possibly) long-term therapeutic decisions are made.

At the time of endoscopy, particular attention should be paid to the presence of erythema, erosions, and other signs of esophagitis, and the gastroesophageal

junction should be examined carefully. If there is any suspicion of Barrett’s esophagus, then four-quadrant biopsies should be taken at the gastroesophageal junction, but a gastroesophageal junction of normal appearance should not be biopsied routinely. Antrum and corpus biopsies should be taken for the diagnosis of H. pylori even in the absence of peptic ulceration, given the recent reports of accelerated gastric atrophy in patients with H. pylori taking long-term PPIs. Thus, prophylactic eradication of H. pylori in this group would be mandatory. There still exists a minority opinion that believes that because H. pylori infection is common, and in most circumstances does not lead to harm, establishing whether H. pylori was present may be irrelevant and potentially confusing.

junction should be examined carefully. If there is any suspicion of Barrett’s esophagus, then four-quadrant biopsies should be taken at the gastroesophageal junction, but a gastroesophageal junction of normal appearance should not be biopsied routinely. Antrum and corpus biopsies should be taken for the diagnosis of H. pylori even in the absence of peptic ulceration, given the recent reports of accelerated gastric atrophy in patients with H. pylori taking long-term PPIs. Thus, prophylactic eradication of H. pylori in this group would be mandatory. There still exists a minority opinion that believes that because H. pylori infection is common, and in most circumstances does not lead to harm, establishing whether H. pylori was present may be irrelevant and potentially confusing.

In the absence of Barrett’s esophagus or for Barrett’s esophagus without high-grade dysplasia, the primary goal of treatment of GERD should be to relieve symptoms. Thus, with the identification of minimal or modest esophagitis at endoscopy and mild symptoms, a PPI should be the initial agent of choice. There is no longer much support for initial treatment with either an H2 receptor antagonist or prokinetic agents, given their modest efficacy and the adverse effects noted, particularly at the high dosage levels needed to attain a consistently elevated pH. The cost to the patient in terms of lifestyle and work loss generated by initial failed therapy using such agents is no longer acceptable.

There is uniform agreement that in the event of moderate or severe esophagitis or particularly troublesome symptoms, all patients should be treated with a PPI immediately. If a patient had been placed on H2 receptor antagonist or prokinetic therapy and failed to resolve his or her symptomatology or relapsed, a PPI should be prescribed. Under such circumstances, it is well accepted that PPIs should initially be given at standard doses. In rare instances, when these fail to provide symptom relief for all patients, they may need to be increased to twice-daily dosing or even more to achieve full symptom relief. Based on currently available information, it is felt that the addition of a prokinetic agent to therapy in conjunction with a PPI is likely to be of only marginal benefit for GERD. Once a dose of an H2 receptor antagonist, prokinetic agent, or PPI that relieves symptoms is identified, this dose should be maintained for a period of 3 months. After this time, an attempt should be made to reduce the dose, with the aim of maintaining a stable clinical status (asymptomatic) on half-dose PPIs or, alternatively, on alternative-day therapy. If symptoms recur, then the patient should resume the full dose of PPI and a plan should be formulated for long-term treatment.

The long-term treatment options are either medical therapy, with attempts to reduce the dose of medication occasionally, or consideration for surgery. With regard to patients who might enter long-term therapy, it should be noted that many, particularly those in the older age group, may already be taking several medications. Thus, careful attention should be directed to the druginteraction profile of the various types of PPIs.

Antisecretory drugs

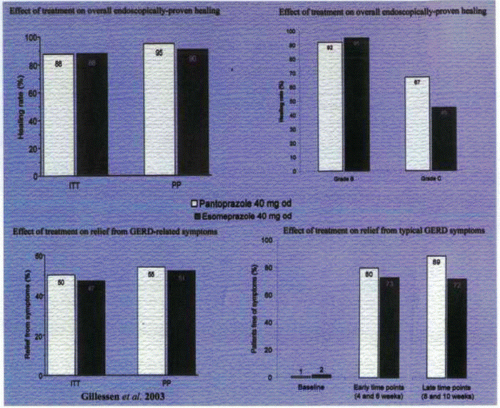

Together with implementing lifestyle modifications (whenever practicable), PPIs should be started as the drugs of choice for erosive esophagitis, achieving healing rates in clinical trials of over 80% at 4 weeks—significantly higher than for any other medication. Several recent publications have indicated that the optimal dose for healing moderate to severe erosive esophagitis is 40 mg of a PPI daily. Widespread use of PPIs testifies to the symptomatic benefits that they also offer in nonerosive disease. PPIs act by covalently binding to cysteine residues in H,K-ATPases (the proton pumps) in the membranes of the secretory canaliculi of parietal cells. Differences in the molecular structures of specific PPIs result in different cysteine residues being targeted. For example, all PPIs bind to cys 813; lansoprazole also binds to cys 321, and pantoprazole binds, in addition, to cys 822. Pharmacologic studies in a variety of test systems in vitro in animals and human experimental and pharmacodynamic data indicate that the ability of pantoprazole to target cys 822 may lead to a more prolonged effect. However, milligram for milligram, all drugs in this class appear comparable in their effects clinically, because human studies have not revealed significant or consistent differences between the drugs with regard to clinical or endoscopic end points or side-effect profiles. More detailed studies involving head-to-head comparisons between the various available drugs are needed to determine whether small pharmacokinetic differences between the PPIs translate into clinical practice. Improvement in PPI therapy is likely to result from a longer dwell time in blood or on the pump itself, since binding to cys 813 may be reversed in part by cellular gluthione. The improvement of esomeprazole, 40 mg, as compared to omeprazole, 20 mg, is attributed to a

longer steady state of the S-enantiomer in the blood due to slower metabolism of this enantiomer as compared to the R-enantiomer. Other means of increasing the dwell time in the blood may be developed.

longer steady state of the S-enantiomer in the blood due to slower metabolism of this enantiomer as compared to the R-enantiomer. Other means of increasing the dwell time in the blood may be developed.

In comparing the results of clinical trials of PPIs, it may also be important to consider the metabolism of PPIs by cytochrome p450 CYP2C19. Clinically important polymorphisms of this enzyme have been described, occurring at varying frequencies in differing populations. Differences between clinical outcomes from studies performed in different parts of the world and an apparent failure of the drugs to control symptoms in some subjects may be explained and rationalized in some instances after a consideration of these polymorphisms. Ideally, agents lacking significant pharmacologic interaction with the cytochrome p450 enzymes are desirable, because many GERD patients are taking numerous other drugs for coexisting diseases and are at risk for drug interactions.

Because the proton pumps on the parietal cell are most accessible to PPIs when acid secretion is maximally stimulated after prolonged fasting, PPIs are most efficacious in inhibiting acid secretion when taken by patients shortly before a protein-rich breakfast. However, this may not be the case for many people who no longer eat such a meal on a daily basis or for those patients with dominant nocturnal symptoms. In these instances, might a better strategy be to take the drug before dinner instead of, or in addition to, the morning dose?

Future challenges to improving medical therapy include the problems of large-volume refluxers who experience symptoms despite reasonable neutralization of the intragastric pH and the optimal management of patients whose symptoms are predominantly nocturnal—any advantage in the addition of H2 receptor antagonists to PPI dosing is rapidly lost due to the development of tolerance. In the future, the “on demand” use of PPIs for symptoms of heartburn in patients with nonerosive reflux disease may perhaps provide reasonable symptom relief with a considerable reduction in medication use compared with daily therapy. Additionally, such a strategy may provide a means to taper a patient from a daily dependence on PPIs without a severe acid/gastrin rebound effect.

The advent of intravenous PPIs has allowed for the achievement of more profound and more sustained predictable acid suppression in the absence of the development of any tolerance. This may provide clinical benefit for patients suffering from pathologic hypersecretory conditions, such as Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, or for those patients with severe erosive reflux disease who are unable to tolerate oral therapy, for example. However, with a paucity of rigorous data to support their usefulness, their role in the armamentarium of therapy is currently unclear.

Prokinetic agents

The impact of impaired esophageal or gastric motility on the development of reflux symptoms is conflicting and the prokinetic agents currently available disappointing in terms of efficacy and side effects. Thus, except for specific patients with documented motility abnormalities, there is little role for prokinetic agents in the treatment of GERD or NERD.