Colonoscopy

Colonoscopy is performed with the patient lying in the left lateral decubitus (Sims) position. Flexible sigmoidoscopy will not be discussed separately because it duplicates the initial maneuvers of colonoscopy. Concentrate on passing the scope safely and atraumatically. Inspect the region as the scope is withdrawn. Use as little air insufflation as possible to ensure patient comfort and to facilitate passage of the scope. This procedure is used to introduce the topography of the colon.

SCORE™, the Surgical Council on Resident Education, classified colonoscopy with or without biopsy or polypectomy as an “ESSENTIAL COMMON” procedure.

STEPS IN PROCEDURE

Assure intravenous access and provide sedation, if desired

Position patient in left lateral decubitus position

Perform digital rectal examination

Pass lubricated colonoscope past anal sphincters

Pass Scope Under Direct Vision to Cecum

Use as little insufflation as possible

The rectum hugs the curve of the sacrum and has three prominent valves

At the pelvic brim, angulation marks the entry into the mobile sigmoid colon

The next angulation is encountered at the splenic flexure

The three haustra of the transverse colon usually give it a triangular cross-section

The next angulation is the hepatic flexure (sometimes aspirating some air helps)

The cecum shows convergence of taeniae, appendiceal orifice and ileocecal valve may be seen

Inspect the entire bowel as you slowly withdraw the scope

HALLMARK ANATOMIC COMPLICATIONS

Missed lesions due to blind spots

Perforation

LIST OF STRUCTURES

Rectum

Transverse rectal folds (valves of Houston)

Sigmoid colon

Descending (left) colon

Splenic flexure

Transverse colon

Hepatic flexure

Ascending (right) colon

Cecum

Ileocecal valve

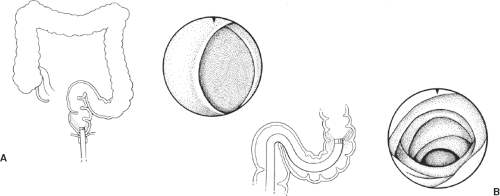

Rectosigmoid (Fig. 96.1)

Technical Points

Perform a digital rectal examination first to lubricate the anal canal and to confirm that no low obstructing lesions are present. If stool is encountered, consider rescheduling the examination after completion of a more adequate bowel prep.

Place the index finger of your dominant hand on the tip of the scope and press the tip, angled at about 45 degrees, against the anus. Instruct the patient to bear down. This will relax the sphincters and facilitate passage of the scope. Press the scope into the anal canal. Note that the rim of the scope is elevated, which makes insertion of the tip en face difficult, if not impossible.

The rectum curves posteriorly to hug the hollow of the sacrum. Insufflate enough air to identify its lumen. The valves of Houston may be visible.

At the pelvic brim, the relatively straight rectum blends imperceptibly with the mobile sigmoid. The length and mobility of this segment vary considerably from individual to individual and may be altered by prior surgery. Try to traverse the sigmoid using as little length of the scope and as little air insufflation as possible.

Anatomic Points

Flexible endoscopy has significantly decreased the incidence of perforation of the rectum. However, because perforations still occur, one should be aware of the anatomy and relationships of the rectum and anal canal. As the terminal rectum penetrates the pelvic diaphragm, it makes an approximate right-angled bend. From the standpoint of the endoscopist inserting an instrument into the anus, this bend occurs about 4 cm proximal to the anal verge (here defined as the transition zone where the dry, hirsute, perianal skin changes to the moist, squamous epithelium lining the anal canal). This necessitates directing the tip of the instrument toward the concavity of the sacrum. Immediately anterior to this point of angulation are the median prostate gland and paramedian seminal vesicle in male patients, and the vagina in female patients. In male patients, more proximally, the anterior rectal wall is in contact with the urinary bladder. Still further from the anal verge (about 7.5 cm in males and 5.5 cm in females), the peritoneum is reflected from the anterior surface of the rectum to the posterior surface of the urinary bladder (in males) or the uterus (in females), forming the rectovesical or rectouterine pouch (cul-de-sac of Douglas), respectively. This is the most dependent recess of the peritoneal cavity; thus, it can fill with peritoneal fluid, pus, or loops of bowel.

The terminal large bowel is divided into a proximal rectum and terminal anal canal. From the anal verge, the anal canal extends to the pectinate line, a distance of about 1.5 cm. At this line, the stratified squamous epithelium changes to columnar cells characteristic of large bowel mucosa. At approximately this line, several changes occur: The arterial supply changes from the more caudal inferior rectal arteries to the more proximal middle and superior rectal (hemorrhoidal) arteries, the venous return changes from tributaries of the caval system to tributaries of the portal system, the lymphatic drainage pattern changes from drainage to the inguinal nodes to drainage to the internal iliac or inferior mesenteric nodes, and the nerve supply changes from somatic innervation by the pudendal nerves to autonomic innervation (sympathetic and parasympathetic) from hypogastric plexuses.

The rectum extends from the pectinate line to the level of the third sacral vertebra, a distance of about 12 to 15 cm. The lowest part of the rectum, which is entirely below the peritoneal reflection, is significantly wider than the anal canal and is capable of great dilation; this is the rectal ampulla. It is the terminal ampulla that makes the approximate right-angled bend, termed the perineal flexure. The only features of note in the normal rectum are the transverse rectal folds (valves of Houston). Typically, there are three folds: The most distal one (4 to 7 cm from the anal verge) on the left, an intermediate one (8 to 10 cm from the anal verge) on the right, and the most proximal one (10 to 12 cm from the anal verge), again on the left. The number of transverse folds, however, can vary from one to five, and their placement may be reversed. Finally, it should be noted that the rectum lacks the characteristic haustra of the colon. This is a result of the dispersal of the musculature of the three taeniae coli to form a circumferential longitudinal muscle layer of uniform thickness.

Endoscopically, the sigmoid colon can be distinguished by well-marked semilunar folds. In addition, the mucosa in this region is velvety in appearance. Although the length and disposition of the sigmoid colon are variable, that it is suspended on a mesentery enables it to be somewhat straightened by the passage of the endoscope. The first part entered—the terminal sigmoid—typically lies to the right of the midline.