Cholecystectomy, Common Bile Duct Exploration, and Liver Biopsy

The safest way to perform an open cholecystectomy is from the top down, rather than retrograde (bottom up), as is done during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. This is particularly important because open cholecystectomy is generally reserved for the most difficult situations, where there is a lot of inflammation, or for failure of the laparoscopic approach. Top-down dissection reserves division of the cystic duct until the gallbladder is fully mobilized, minimizing the chance of injury to the bile duct.

The traditional top-down approach to open cholecystectomy as described here uses early ligation and division of the cystic artery to minimize bleeding. A tie is then placed around the cystic duct to minimize the chance of stone passage into the bile duct, but the duct is not divided until late in the dissection. These steps are not always safe or feasible in cases of severe inflammation. In that case, do not hesitate to simply dissect from top down, ligating the artery and duct as encountered. This chapter also details an important bail-out option, subtotal cholecystectomy, which is useful in the most difficult cases.

Hallmark Anatomic Complications—Cholecystectomy

Bile duct injury

Bleeding from cystic artery or hepatic artery

Retain bile duct stone

List of Structures

Liver

Gallbladder

Infundibulum (Hartmann’s pouch)

Cystic duct

Common hepatic duct

Bile duct

Ligamentum teres hepatis

Right and left hepatic arteries

Cystic artery

Cholecystoduodenal ligament

Cystohepatic (Calot’s) triangle

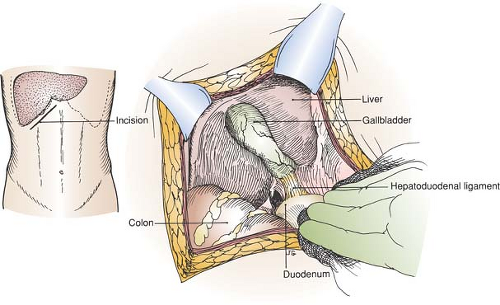

Incision and Exposure of the Gallbladder (Fig. 63.1)

Technical Points

In most patients, a right-sided subcostal (Kocher) incision provides the best exposure. If the subcostal angle is very acute, a right paramedian incision may be chosen instead, especially in a slender patient.

Make the incision two fingerbreadths below the right costal margin and parallel to it. Divide the anterior rectus sheath sharply. Pass a long Kelly hemostat under the rectus abdominis muscle and divide it with electrocautery. Occasional small arteries

may require suture ligation. Pick up and incise the posterior rectus sheath and preperitoneal fat to enter the abdomen. Medially, the ligamentum teres hepatis may need to be divided, particularly if exposure is difficult and surgery on the bile duct is anticipated.

may require suture ligation. Pick up and incise the posterior rectus sheath and preperitoneal fat to enter the abdomen. Medially, the ligamentum teres hepatis may need to be divided, particularly if exposure is difficult and surgery on the bile duct is anticipated.

Steps in Procedure—Cholecystectomy

Right subcostal (Kocher) incision

Divide ligamentum teres hepatic

Kelly clamp on fundus of gallbladder (decompress first, if tense)

Divide adhesions to omentum, pack omentum and colon down

If dissection is difficult because of inflammation, do not attempt to find cystic artery and duct at this point

Incise peritoneum over gallbladder several millimeters from liver and dissect in submucosal plane of gallbladder, working from the top down

Divide peritoneum over Calot’s triangle and posterior peritoneum

Identify and divide cystic artery

Identify and Divide Cystic Duct

If cholangiogram is needed, do not completely divide cystic duct

Make small nick in anterior surface of cystic duct

Insert catheter and secure in cystic duct

Remove gallbladder

If Adhesions are Severe, Consider Subtotal Cholecystectomy

Leave as much of back wall of gallbladder as necessary

Remove anterior part of gallbladder as far down as possible

Secure cystic duct from inside gallbladder with pursestring suture

Destroy remaining mucosa of gallbladder with electrocautery

Place omentum and closed suction drain into subhepatic space

Close incision in usual fashion

Explore the abdomen. Pass a hand over the right lobe of the liver and pull down, allowing air to enter the subphrenic space and providing increased exposure of the subhepatic region. Filmy adhesions between the gallbladder and gastrocolic omentum or transverse colon may need to be cut.

If the gallbladder is tense and acutely inflamed, preliminary decompression with a trocar will decrease the chance of uncontrolled spillage of infected bile during dissection. Place a pursestring suture of 3-0 silk on the top of the gallbladder in an easily accessible location. Support the gallbladder with the left hand and insert a trocar through the center of the pursestring. Aspirate bile and calculous material from the gallbladder. Withdraw the trocar, taking care not to spill bile, and tie the pursestring suture to close the hole. Obtain a culture of the bile.

If the gallbladder is not tense, place a Kelly clamp on the fundus of the gallbladder and pull down and out. Use the clamp to gain traction and expose the cystohepatic (Calot’s) triangle. Place packs to depress the colon and to hold the stomach and duodenum medially out of the field.

Anatomic Points

A short Kocher incision does not cause any functional deficit of the rectus abdominis muscle. However, a very long Kocher incision may result in weakness of the rectus, especially if several segmental nerves are divided. The superior epigastric artery and vein lie posterior to the rectus abdominis muscle,

about halfway (at this level) between the linea alba and the costal margin. These vessels are generally small and are either divided with electrocautery or ligated and divided.

about halfway (at this level) between the linea alba and the costal margin. These vessels are generally small and are either divided with electrocautery or ligated and divided.

The falciform ligament (and its contained ligamentum teres hepatis, in the free edge of the falciform ligament) runs from the umbilicus to the fissure separating the right and left lobes. This lies to the right of the midline, so the falciform ligament is oriented with its left surface in contact with liver and its right in contact with the anterior parietal peritoneum. If the falciform and round ligaments must be divided, this should be done between clamps. The reasons for this are twofold. First, the round ligament, which is the obliterated left umbilical vein, may retain a patent lumen. Second, paralleling the round ligament are a variable number of paraumbilical veins, which provide a potential collateral circuit between the portal vein and the caval system via the superficial veins of the abdomen.

The right and left hepatic ducts leave their corresponding liver lobes and unite close to the porta hepatis to form the common hepatic duct, typically the most anterior tubular structure in this region. The cystic duct, which drains the gallbladder, joins the common hepatic duct at a variable distance from the porta hepatis and at a variable angle. This union forms the bile duct.

The gallbladder is a diverticulum of the extrahepatic biliary tree. From the cystic duct, the gallbladder is divided into a narrow neck (in which spirally arranged folds of mucosa form the so-called valve of Heister), a tapering body, and an expanded fundus that extends beyond the inferior border of the liver. Frequently, an asymmetric bulging of the right side of the neck may occur. This bulge, known as the infundibulum of the gallbladder (or Hartmann’s pouch), may be bound down toward the first part of the duodenum by a cholecystoduodenal ligament, the right edge of the lesser omentum. This ligament must be divided and the infundibulum (Hartmann’s pouch) mobilized to clearly identify the cystic duct.

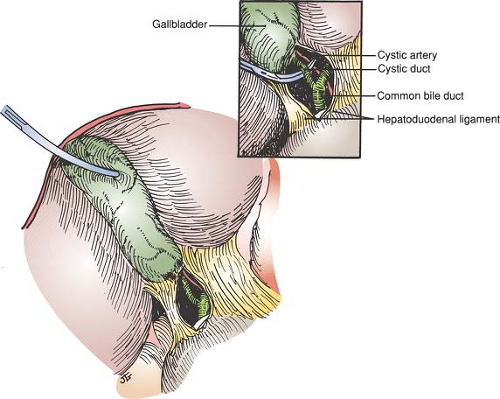

Identification of the Cystic Artery and Cystic Duct (Fig. 63.2)

Technical Points

Divide any filmy adhesions that remain between the gallbladder and colon or omentum. Place a second Kelly clamp farther down on the gallbladder; be careful to clamp the gallbladder and not the cystic or bile duct. Incise the peritoneum overlying the cystohepatic (Calot’s) triangle and dissect bluntly with a Kitner dissector. Push fatty and areolar tissues away from the gallbladder to expose the bile duct, cystic duct, and cystic artery.

Sometimes the gallbladder is so inflamed that it is adherent to the duodenum or bile duct. If this appears to be the case, abandon the attempt to identify and ligate the cystic artery and cystic duct and simply proceed directly to top-down removal of the gallbladder (Fig. 63.3).

Identify the cystic duct passing from the gallbladder to the bile duct. Clean the duct gently and pass a right-angle clamp behind it. Double-loop the duct with a 2-0 silk suture to provide temporary but atraumatic occlusion of the duct. This helps to prevent small stones from being forced down into the bile duct during the dissection and facilitates the performance of a cholangiogram of the cystic duct.

Next, identify the cystic artery, which typically passes superior to the cystic duct and runs along the anterior surface of the gallbladder. Clean the cystic artery and divide it, securing the ends with 3-0 silk ligatures. Anomalies are common in this area; an unusually large cystic artery should raise the suspicion that the vessel may, in fact, be an anomalous right hepatic artery. Dissect along the course of the vessel to see whether it terminates on the gallbladder or loops back up into the liver.

If the cystic artery is inadvertently divided, do not attempt to clamp it. Blind clamping in a bloody field may cause bile duct injuries. Simply pass the index finger of your nondominant hand into the space behind the bile duct and duodenum and compress the pedicle including the bile duct, hepatic artery, and portal vein (Pringle maneuver) with your fingers, slowing the bleeding so that the vessel can be identified and clamped with surety. A vascular clamp may also be used to provide secure temporary occlusion.

Anatomic Points

The boundaries of the cystohepatic (Calot’s) triangle are the cystic duct inferiorly, the common hepatic duct medially, and the right lobe of the liver superiorly. It contains the right hepatic duct and right hepatic artery (usually posterior to the duct) in the superior part of the triangle, and the cystic artery more inferiorly. Anomalous vessels and bile ducts are common. The right hepatic artery can lie anterior to the right hepatic duct, or it may be up to 1 cm distant from the duct. Because its course briefly parallels the cystic artery, it can be mistaken for the latter vessel. The cystic artery, typically a branch of the right hepatic artery, can arise from any artery in the vicinity (e.g., the left hepatic, common hepatic, gastroduodenal, superior mesenteric, etc.). However, regardless of its origin, it usually passes through the cystohepatic (Calot’s) triangle.

Skeletonization of the cystic duct from the neck of the gallbladder to the bile duct is necessary, because it allows the surgeon to verify its identity. Variations in the biliary apparatus are also common. There can be accessory hepatic ducts (usually from the right), which can be mistaken for the cystic duct; bifurcated cystic ducts; multiple cystic ducts; and even absence of a cystic duct.

Removal of the Gallbladder (Fig. 63.3)

Technical Points

With the cystic artery and cystic duct controlled, dissection now progresses from the fundus of the gallbladder down. Incise the peritoneum overlying the gallbladder until the blue submucosal plane, which is superficial to a network of small vessels, is identified. Dissection in this plane will allow removal of the gallbladder without injury to the liver and with a minimum of blood loss. Carry the peritoneal incisions laterally as far as exposure will allow. After the correct plane has been identified, use electrocautery to incise the peritoneum over a right-angle clamp.

Hold the Kelly clamp and the gallbladder with your nondominant hand, moving the gallbladder from side to side as required to expose the attachments between the gallbladder and liver. Cut these attachments sharply, remaining as much as possible in the submucosal plane.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree