Central Pancreatectomy

Daniel J. Delitto

Jose G. Trevino

DEFINITION

Central pancreatectomy (occasionally referred to as median or middle pancreatectomy) is a conservative resection of the neck and body of the pancreas in order to conserve endocrine and exocrine pancreatic function. This segmental resection also preserves surrounding structures including the duodenum, spleen, biliary tract, and gallbladder. Central pancreatectomy has been described for benign, premalignant, and low malignant potential tumors located in the pancreatic neck and proximal portion of the pancreatic body.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs) are most commonly nonfunctional, but approximately 15% of PNETs actively secrete insulin, glucagon, vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), pancreatic polypeptide (PP), somatostatin, or gastrin. Neuroendocrine tumors have known malignant potential and resection is indicated in appropriate surgical candidates. PNET is the most frequent diagnostic indication for central pancreatectomy.

Mucinous cystadenomas (MCAs) account for 2% of all pancreatic neoplasms and approximately 25% of cystic neoplasms.1,2 These tumors tend to be larger than SCAs, contain a mucin-secreting epithelial lining, and have no communication with the pancreatic ductal system. MCAs are considered dysplastic lesions with premalignant potential and resection is indicated in suitable surgical candidates.

Pseudopapillary tumor (SPT) is a rare cystic-appearing neoplasm with malignant potential in approximately 5% of cases. The hypodense areas seen on imaging represent necrosis of solid papillary vascular stalks that slough as the tumor grows. Resection is indicated upon diagnosis. As these rare lesions are typically large at the time of diagnosis, central pancreatectomy as a viable surgical approach will be incredibly unusual.

Serous cystadenomas (SCAs) represent approximately 1% of all pancreatic neoplasms and 33% of pancreatic cystic neoplasms.2 These lesions contain a true epithelium and do not communicate with the pancreatic duct. Indications for surgical intervention for SCAs include symptomatic lesions or rapid growth with solid components. Otherwise, observation of SCAs is recommended. As with SPT, these lesions tend to be large at the time of diagnosis; central pancreatectomy will rarely be a viable option.

Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs) are continuous with the pancreatic ductal system. These lesions may be classified as either branch-type or involving the main pancreatic duct. Main duct neoplasms may be invasive in up to 50% of cases and central pancreatectomy is not appropriate. Branch-type IPMNs should be resected if they are symptomatic, contain concerning radiographic findings (e.g., a mural nodule, thickened septae, or a ductal stricture), high-grade atypia, strong family history of pancreatic cancer, or size greater than 3 cm. As surgical therapy for IPMN includes reduction of malignant potential, the authors do not advocate central pancreatectomy for IPMN—the surgical goal for these patients is not parenchymal preservation.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Early symptoms of benign pancreatic lesions may include vague abdominal pain or bloating, nausea, and weight loss. More advanced lesions may present with gastric outlet obstruction, jaundice, or recurrent pancreatitis. However, most of these lesions are identified incidentally with cross-sectional imaging. In particular, lesions amenable to central pancreatectomy are typically small (˜1 to 2 cm) and are generally asymptomatic.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

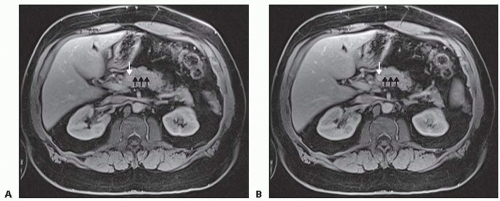

Pancreatic protocol triple-phase (arterial, late arterial, and venous phase) contrast-enhanced, multiplanar, thin-slice computed tomography (CT) provides excellent imaging of pancreatic parenchymal and ductal anatomy and is typically the diagnostic method of choice for characterizing pancreatic tumors. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) may further characterize the relationship of the lesion to the pancreatic duct (FIG 1). Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) may allow for fine needle aspiration (FNA) biopsies. Diagnostic characteristics of each lesion are described.

PNETs appear as hypervascular lesions on thin-slice CT or MRI scans. Somatostatin receptor scintigraphy (SRS) has a high sensitivity for most PNETs, with the exception of insulinomas. EUS may further characterize lesions near the pancreatic head, which typically have a hypoechoic appearance compared to normal pancreatic parenchyma. FNA or core needle biopsy sampling can confirm the presence of PNETs with immunohistochemical staining of cell block or tissue for chromogranin. Functional tumors are diagnosed on a biochemical basis.

MCAs are typically seen in younger women and may contain loculated lesions with multiple septae. More commonly, however, these lesions are seen as larger unilocular cysts. EUS and FNA reveal viscous, mucinous fluid with high carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) levels and low amylase.

SCAs may contain a “starburst” or honeycomb pattern of central scarring on CT imaging. EUS reveals a characteristic thin-walled capsule with thin septae. If FNA is performed, it often yields serous fluid with low amounts of CEA and mucin.

SPTs present in young females (mean age 25 to 30 years) typically as a large mass in the body or tail. These lesions contain hypodense areas representing sloughed, necrotic papillary stalks with internal calcifications. FNA with immunostaining may reveal neuron-specific enolase, vimentin, and α1-antitrypsinase expression. Aggressive surgical resection is

warranted even in the presence of local invasion or metastatic disease.3,4

IPMNs are diagnosed with CT or MRCP. EUS with FNA reveals high amylase and CEA levels. Additionally, K-ras mutation and loss of heterozygosity are malignant characteristics. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) will show continuity with the main pancreatic duct.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Preoperative Planning

A complete history and physical of any patient undergoing central pancreatectomy is essential, paying close attention to signs of malignancy including weight loss or new-onset diabetes. A prior history of jaundice or pancreatitis should also be solicited. Basic blood chemistries should be obtained as well as a hepatic function panel, complete blood count, and coagulation studies. Serum tumor markers, including CEA, carbohydrate antigen (CA 19-9), and α-chromogranin should be obtained. When indicated, additional studies to characterize functional PNETs are warranted.

Central pancreatectomy may be considered for lesions less than 3 cm located deep within the pancreatic neck or proximal body or situated near the main pancreatic duct; such lesions are not amenable for enucleation. The length of remnant distal pancreas should maximize functional endocrine tissue. To this effect, recommendations from Iacono et al.5 include a minimum length of 5 cm for the distal pancreatic stump.

Contraindications to resection include evidence of invasive malignancy and chronic or focal pancreatitis not involving the pancreatic neck or body. Importantly, central pancreatectomy is contraindicated when the tail of the pancreas receives its only blood supply from the transverse pancreatic artery, as this will be ligated during the operation.5

POSITIONING

The patient is placed in supine position, with the table placed into slight reverse Trendelenburg. Two large-bore peripheral intravenous (IV) lines should be established and, if the patient has cardiovascular comorbidities, arterial blood pressure monitoring is advisable.

TECHNIQUES

Laparoscopic central pancreatectomy has been reported by experienced surgeons to be feasible and safe. Port site placement for a minimally invasive approach is shown in FIG 2. The minimally invasive operation proceeds in the order described in the following text.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree