Bone Lesion/Tumor: Diagnosis and Margins

SURGICAL/CLINICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Goal of Consultation

Determine if a bone lesion is benign/reactive or malignant

Evaluate margins after a definitive resection of a malignant bone tumor

Change in Patient Management

Reactive lesions may be followed clinically or excised

Benign neoplasms are often excised or curetted without need to document negative margins

Low-grade malignancies are resected, often widely (if possible) and with margin assessment

Complete curettage may also be attempted in some well-localized tumors

High-grade malignancies may be treated with radiation/chemotherapy prior to resection or resected before treatment

Positive bony &/or marrow margins may generate additional resection or possibly closure and subsequent adjuvant therapy

Clinical Setting

Patient age ranges from pediatric to adult

Lytic &/or blastic lesions identified on radiograph

May be incidentally discovered on plain film during evaluation for other conditions

Bone destruction &/or soft tissue invasion often apparent in locally aggressive &/or malignant tumors

Malignancies are more likely than benign lesions to cause pain

SPECIMEN EVALUATION

Radiograph

Review of appropriate patient radiographs prior to receipt of specimen is highly recommended

Radiologist’s differential diagnosis is essential for correlation with pathologic findings

Knowing the specific bone as well as anatomic region of bone involved is diagnostically useful information

Identification of an aggressive growth pattern radiographically can be essential in helping classify a low-grade bone malignancy intraoperatively

Gross

Bone specimens sent for intraoperative consultation and diagnosis are almost invariably composed of small fragments of soft tissue and bone

Intraoperative margins sent for bone tumors are either peripheral soft tissue margins or intramedullary marrow margins

Frozen Section

Hard bony fragments should be separated from soft tissue fragments

Softer bony fragments can be frozen, but harder bone may damage cryostat blade &/or distort frozen section

Tissue that can be cut easily with a scalpel blade can generally be sectioned on a cryostat

All tissue should be frozen unless entire lesion has been curetted and sent to pathology

If completely curetted, representative tissue from specimen usually suffices

These specimens are usually from presumptively benign lesions

Cytology

Touch prep slides of lesional tissue may be helpful if metastatic carcinoma is suspected

MOST COMMON DIAGNOSES

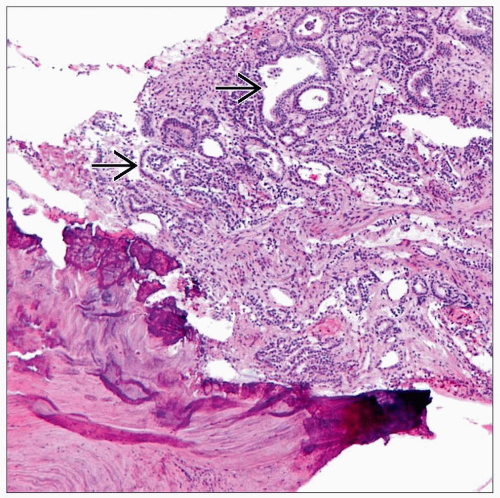

Metastatic Cancer

Far more common than primary bone tumors

Carcinoma is most common, but melanoma, sarcoma, or lymphoma may also metastasize to bone

Must always be considered in patients > 45 years of age

Patients often have history of cancer elsewhere as well as prior metastatic disease (e.g., to lymph nodes, lung)

Any bone may be involved

Most often proximal humerus, proximal femur, or spine

Histologic appearance depends on primary tumor

Usually adenocarcinoma (most common primary sites include breast, lung, kidney, prostate, liver, and thyroid)

Some metastatic carcinomas (particularly from prostate) are osteoblastic and produce focal to abundant woven bone

Immunohistochemical studies performed on permanent sections may be necessary for classification if no primary site is known

Decalcification can diminish immunoreactivity for some antigens

If possible, softer areas of tumor should be separated and not decalcified

Osteosarcoma

Most commonly seen in young patients between 10 and 20 years of age

2nd peak occurs in patients > 50 years of age who have a predisposing condition (e.g., radiation, Paget disease)

Imaging often shows a large permeative and destructive lesion in metaphysis/diaphysis of a long bone, most commonly around region of knee (˜ 50% of cases)

Most cases show sheets of frankly malignant cells with a high level of mitotic activity

Diagnosis depends upon identification of pink seams of osteoid or immature bone directly produced by malignant cells

Some tumors may show focal or prominent cartilaginous differentiation, leading to possible confusion with chondrosarcoma

Younger age and presence of cellular sheets of malignant cells (± osteoid) favor osteosarcoma

Other variant morphologies include fibroblastic (spindled), small cell, clear cell, telangiectatic, and giant cell rich

Enchondroma

Often painless unless associated with a fracture

Imaging often shows a small, well-circumscribed lesion without locally aggressive features in diaphysis/metaphysis of long bones

In long bones: Generally composed of fragments and nodules of bland hyaline cartilage, often with a thin pink seam of peripheral bone

Chondrocyte cellularity is often low and with minimal or no nuclear atypia

In small bones of hands and feet: Often much more cellular and may demonstrate mild nuclear atypia and myxoid matrix degeneration

Clinical and radiologic correlation to evaluate for pathologic cortical bone disruption and soft tissue extension is most helpful in excluding a chondrosarcoma

In some cases, it can be extremely difficult, if not impossible, to histologically distinguish an enchondroma from a low-grade chondrosarcoma

Correlation with imaging is often critical in making this distinction

In ambiguous cases, a diagnosis of “low-grade cartilaginous lesion, final diagnosis deferred to permanent sections” is appropriate

Any subsequent curetted tissue should be submitted for permanent histologic evaluation

Chondrosarcoma

Often painful

Imaging generally shows an irregular, large, and destructive tumor, often with cortical disruption and soft tissue extension, involving metaphysis/diaphysis of long bones

Clear cell chondrosarcoma (variant) characteristically arises in epiphysis of long bones

Cellularity and chondrocyte nuclear atypia varies widely depending on grade, but most cases show a higher degree of both than seen in benign cartilage or enchondroma

Chondrocyte necrosis and prominent matrix degeneration are also more common in chondrosarcoma

Chondrosarcoma of small bones of hands and feet is very rare and requires evidence of true bony or soft tissue invasion for diagnosis

Dedifferentiated chondrosarcoma may show cellular, noncartilaginous high-grade sarcoma or neoplastic cartilage or both, depending on what portion of tumor is sampled at time of frozen section

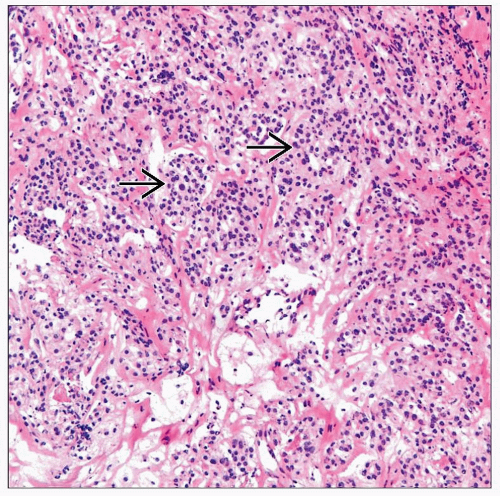

Ewing Sarcoma

Most common in patients < 20 years of age

Painful, enlarging mass, often with soft tissue swelling

Imaging shows a large, poorly defined destructive tumor most often centered in metaphysis or diaphysis of long bones or flat bones of pelvis

Sheets of monomorphic small, round cells with scanty cytoplasm (“small round blue cell tumor”) within a variably fibrous background

Most cells have finely distributed chromatin and inconspicuous nucleoli

Necrosis is often abundant

Diagnosis of “malignant small round blue cell tumor, final diagnosis deferred to permanent sections” is often appropriate

Must exclude other morphologically similar neoplasms such as small cell osteosarcoma, mesenchymal chondrosarcoma, or lymphoma

Confirmatory ancillary testing (IHC, FISH, etc.) is required on permanent sections

Giant Cell Tumor

Typically occur in adults (age range: 25-45)

Localization to epiphysis of a long bone is characteristic, similar to chondroblastoma and clear cell chondrosarcoma

Also shows metaphyseal extension in many cases

Tumor is often locally aggressive and may show limited soft tissue extension

Composed of sheets of multinucleated osteoclast-like giant cells in a background of bland, monomorphic ovoid or spindled stromal cells

Giant cells may be very large (> 50 nuclei)

Stromal cells should not show malignant cytologic features or atypical mitoses

Evidence of frank malignancy should raise possibility of other tumors, such as metastatic carcinoma, osteosarcoma, dedifferentiated chondrosarcoma, etc.

May contain areas of aneurysmal bone cyst (ABC)

Epiphyseal location suggests secondary ABC over primary ABC

Chondroblastoma

Typically occurs in skeletally immature patients, with open growth plates (age range: 10-25 years)

Localization to epiphysis or apophysis of a long bone is characteristic

Imaging shows well-defined tumor of variable size, often with sclerotic margins

Contains large number of osteoclast-like giant cells, similar to giant cell tumor

Predominant cell type (chondroblast) is generally pink, epithelioid, and contains a nucleus that is sometimes grooved

Identification of stromal “chicken wire” calcification and fragments of cartilage is common

Distinguishing chondroblastoma from giant cell tumor

Young age, epithelioid “fried egg” cells with grooved nuclei, “chicken wire” calcification, and presence of cartilage all favor chondroblastoma

May contain areas of aneurysmal bone cyst

Fibrous Dysplasia

Most common in young to middle-aged patients; often asymptomatic

May present as solitary or multiple lesions (either within same or different bones)

Most common in long bones

Other sites (e.g., ribs and craniofacial bones) may be involved

Imaging shows a well- circumscribed intramedullary tumor, most commonly in diaphysis and metadiaphysis

Composed of a mixture of fibroblasts and immature (woven) bone trabeculae

Spindled fibroblasts are bland and may demonstrate a storiform growth pattern

Stroma is often collagenous but may be myxoid

Woven bone trabeculae are characteristically irregularly shaped, discontinuous, and often lack osteoblastic rimming

Woven bone production can be focal in some tumors and may not be sampled, potentially leading to diagnostic difficulty

Does not demonstrate an infiltrative or permeative growth pattern through preexisting lamellar bone (finding suggests low-grade osteosarcoma)

Aneurysmal Bone Cyst (ABC)

Most commonly arise in young patients (< 20 years) in metaphyseal region of long bones

Imaging generally shows an expansile, lytic, and cystic lesion, often with fluid levels due to blood

Composed of variably thick cyst walls containing bland spindled to ovoid cells, scattered giant cells, and focal seams of osteoid

Frankly malignant cells are inconsistent with diagnosis and may suggest telangiectatic osteosarcoma

Epiphyseal lesions with the appearance of ABC are usually different tumors (giant cell tumor, chondroblastoma, etc.) with a secondary ABC

Osteomyelitis

Patients often complain of pain and systemic symptoms

Can easily mimic a neoplasm on imaging

Early osteomyelitis shows fragments of mature lamellar bone associated with granulation tissue, necrotic bone, and collections of acute inflammatory cells

Chronic osteomyelitis often shows intertrabecular loose fibrosis and a more prominent plasma cell infiltrate

Fibrous dysplasia and low-grade osteosarcoma show a cellular spindle cell proliferation rather than loose fibrosis

Plasma cell neoplasms contain sheets of plasma cells and lack granulation tissue

Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis (Eosinophilic Granuloma)

Usually presents in first 3 decades of life

May be solitary (eosinophilic granuloma) or multifocal

Systemic disease involves multiple organ systems and frequently occurs in first 2 years of life

Most common in craniofacial bones but can involve any bone

Imaging usually shows small, well-defined lesion (may have “punched out” appearance)

Composed of irregular sheets and nests of pink histiocytic cells (Langerhans cells) within a typically prominent mixed chronic inflammatory infiltrate

Langerhans cell nuclei are generally ovoid with nuclear grooves (coffee bean shaped) or notched

Eosinophils are variably prominent, and may show eosinophilic abscess formation

Reactive germinal centers may be present

Inflammation may obscure diagnostic Langerhans cells

Metaphyseal Fibrous Defect (Nonossifying Fibroma/Fibrous Cortical Defect)

Most common in 2nd decade of life

Imaging shows small, well-demarcated, cortical-based lesion in metaphysis of long bone

Painless and asymptomatic, unless large or associated with fracture

Composed of bland spindled fibroblasts in a storiform growth pattern associated with scattered multinucleated osteoclast-like giant cells

Number of giant cells may be striking, but sheets of giant cells are not seen (as in giant cell tumor)

Xanthomatous change and chronic inflammation are commonly identified

Plasma Cell Neoplasm

Very common primary malignant bone tumor

Most patients are middle aged or older

May present as a localized lesion (plasmacytoma) or as a component of widespread disease (plasma cell myeloma)

Composed of sheets of plasma cells demonstrating varying degrees of nuclear atypia

Poorly differentiated plasma cells may be difficult to distinguish from carcinoma, and clinical/radiographic correlation or even deferral may be required

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree