1B01

Key word: Initial Treatment for Coagulopathy of Chronic Renal Failure

Author: Robert A. Meguid, MD, MPH

Editor: Elliott R. Haut, MD, FACS

A 76-year-old dialysis-dependent woman with a history of multiple prior abdominal operations presents to the emergency room with worsening abdominal pain. Workup raises your suspicions for ischemic bowel. She last underwent hemodialysis 3 days prior, and is currently uremic. How will you best prepare the patient for emergent celiotomy?

Administer conjugated estrogens

Administer cryoprecipitate

Administer desmopressin

Arrange for dialysis

Transfuse the patient with packed red blood cells (PRBC)

View Answer

Answer: (C) Administer desmopressin

Rationale:

The patient has chronic renal failure (CRF), which results in a coagulopathy that must be corrected prior to surgery. The mechanism leading to the coagulopathy associated with CRF is thought to be due to uremic inactivation of von Willebrand Factor (vWF). vWF normally binds platelets to collagen, initiating formation of the platelet plug.

Desmopressin, or DDAVP, causes the release of vWF and Factor VIII from the endothelium. Time to effect of DDAVP is within 1 hour of administration and may last for up to 4 hours. DDAVP may also be used for reversal of platelet dysfunction caused by aspirin as well as following cardiopulmonary bypass. Treatment dose is 0.3 µg/kg, and this is typically given as a single dose. Administration of DDAVP avoids the risks associated with blood product transfusion.

Dialysis, while effective at correcting the patient’s uremia, may not immediately correct the coagulopathy. Hemodialysis can correct platelet function but only transiently. The heparin commonly used with dialysis may contribute to the bleeding diathesis. While the effects of hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis may last for up to a few days, the onset of effect and setup is slower than for DDAVP administration.

Transfusion with PRBC may correct the anemia associated with CRF, but does not rectify the coagulopathy caused by uremia.

Infusion of cryoprecipitate can shorten bleeding time for up to 12 hours by increasing Factor VIII and vWF levels. However, supplies may be limited, and a large quantity may be required to correct a uremic coagulopathy, translating into high costs.

Conjugated estrogens are effective at shortening the bleeding time in uremic patients. However, they need to be administered over several days, because onset to effect is 72 hours.

References:

Henke PK, Wakefield TW. Hemostasis. In: Mulholland MW, Lillemoe KD, Doherty GM, Maier RV, Upchurch GR, eds. Greenfield’s Surgery: Scientific Principles & Practice. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011.

Marks PW, Rosovsky R. Chapter 156: Hematologic manifestations of systemic disease: Liver and renal disease. In: Hoffman R, Benz EJ, Shattil SJ, Furie B, Cohen HJ, Silberstein LE, McGlave P, eds. Hematology: Basic Principles and Practice. 4th ed. New York, NY: Elsevier; 2008.

1B02

Key word: Condition Associated with Family History of Cecal Cancer

Author: Robert A. Meguid, MD, MPH

Editors: Thomas H. Magnuson, MD, and Kenzo Hirose, MD, FACS

A 39-year-old male is referred to your clinic for treatment of a cecal mass diagnosed by surveillance colonoscopy. His father, paternal grandmother, and paternal uncle all developed colon cancer by their fifth decade. Mutation of which of the following genes is associated with this man’s disease?

APC

BRCA1

BRCA2

hMSH2

K-Ras

View Answer

Answer: (D) hMSH2

Rationale:

Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC), also known as Lynch syndrome, is an autosomal dominant hereditable disease caused by mutations in DNA mismatch repair genes including hMSH2, hMLH1, hPMS1, and hPMS2. Polyps are smaller than those seen in other familial colorectal cancer syndromes, and usually number less than 100. HNPCC tumors typically originate in the right colon; however, they may present as multiple synchronous cancers. Clinical criteria for the diagnosis of Lynch syndrome include the Amsterdam criteria I and II as well as the Bethesda criteria. Amsterdam criteria I requires that familial adenomatous polyposis be excluded, that three relatives with colorectal cancer, spanning two generations be affected with, one being a first-degree relative of the others, and one with a diagnosis before age 50. Amsterdam II criteria includes three relatives with an HNPCC-associated cancer (colorectal, endometrial, ovarian, stomach, small intestine, biliary tract, ureter, renal pelvis, and sebaceous gland adenomas) with relatives that meet the rest of the criteria of Amsterdam I. Amsterdam I and Amsterdam II have relatively low sensitivities in diagnosing Lynch syndrome of 61% and 78%, respectively, leading to the development of the Bethesda guidelines which expand the criteria, and include synchronous colon cancers, microsatellite instability, and synchronous HNPCC-related cancer. The patient in question meets Amsterdam I criteria and should have his cancer submitted for microsatellite instability testing and undergo genetic counseling and possible germline mutational analysis. Patients with HNPCC should undergo a total colectomy if cancer is suspected.

Mutations in the K-Ras oncogene are associated with greater than 90% of pancreatic cancer. This is currently thought to be a sporadic mutation, and occurs early in the accumulation of gene mutations resulting in the progression toward pancreatic adenocarcinoma, but is not associated with colorectal cancer. Mutations in the tumor suppressor gene APC are associated with the autosomal dominant disorder familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP). In contrast to HNPCC, these patients have hundreds to thousands of polyps present throughout the colon by 25 years of age, which manifest as cancers by 45 years of age. Polyps are small, and are concentrated in the left colon. Treatment of patients with FAP is usually total abdominal colectomy with mucosal proctectomy and ileoanal pull-through. Carrying the BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene mutation is associated with up to an 85% chance of developing breast cancer. Carriers of either mutation have an increased incidence of developing ovarian cancer; however, currently only the BRCA2 mutation is associated with an increased incidence of male breast cancer.

References:

Boland CR, Bresalier RS. Colonic polyps and polyposis syndromes. In: Mulholland MW, Lillemoe KD, Doherty GM, Maier RV, Upchurch GR, eds. Greenfield’s Surgery: Scientific Principles & Practice. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011.

Hruban RH, Goggins M, Parsons J, et al. Progression model for pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6(8):2969-2972.

Morris A. Colorectal cancer. In: Mulholland MW, Lillemoe KD, Doherty GM, Maier RV, Upchurch GR, eds. Greenfield’s Surgery: Scientific Principles & Practice. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011.

Comparison of Clinical Criteria for Hereditary Nonpolyposis Colorectal Cancer (HNPCC)a

1B03

Key word: Treatment of Umbilical Hernia with Ascites

Author: Susanna M. Nazarian, MD, PhD

Editor: Frederick E. Eckhauser, MD, FACS

A 70-year-old man with ascites secondary to cirrhosis presents for elective umbilical hernia repair. Should he be offered repair of his hernia?

No, he should not be offered repair

Yes, if he had a recent myocardial infarction

Yes, if he is leaking ascites from the hernia

Yes, if he is listed for liver transplant

Yes, if it is significantly affecting his lifestyle

View Answer

Answer: (C) Yes, if he is leaking ascites from the hernia

Rationale:

The repair of umbilical hernias in patients with cirrhosis is associated with a high rate of recurrence secondary to the production of ascites and nutritional deficiencies resulting in muscular wasting and fascial thinning. Up to 20% of patients with cirrhosis develop a hernia of the anterior abdominal wall. Surgery on these patients is complicated by the risk of hemorrhage secondary to variceal disruption, peritonitis, postoperative ascites leak, and hepatic decompensation. Therefore, such a surgical undertaking should be considered only in select patients. One indication includes those patients leaking ascites, therefore, placing them at higher risk of peritonitis.

It is of utmost importance to minimize ascites preoperatively. Repair of an umbilical hernia without adequate control of ascites preoperatively contributes to a 73% recurrence rate. Medical control of ascites entails fluid and salt restriction, diuretics, and possibly paracentesis. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) may be used preoperatively to reduce the production of ascites.

Reference:

Marvin MR, Edmond JC. Cirrhosis and portal hypertension. In: Mulholland MW, Lillemoe KD, Doherty GM, Maier RV, Upchurch GR, eds. Greenfield’s Surgery: Scientific Principles & Practice. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2011.

1B04

Key word: Characteristics of NSQIP

Author: Eric S. Weiss, MD, MPH

Editor: Dorry L. Segev, MD, PhD

The fundamental goal of the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) is:

To collect outcome data to measure and improve surgical care outcomes

To identify those surgeons who deliver excellent surgical care

To improve health care in underserved US populations

To model systems for improved use of health care resources

To monitor surgical costs in order to allocate health care

View Answer

Answer: (A) To collect outcome data to measure and improve surgical care outcomes

Rationale:

The American College of Surgeons designed NSQIP to improve surgical quality in the United States. This validated, outcome-based program allows comparisons between hospitals to affect improvement. The program was first used in the Veterans Health Administration (VA) in the 1990s. Operative morbidity and mortality were collected and compared across VA hospitals. With the implementation of this program, morbidity has decreased by 45% and mortality has decreased by 27% in the VA system. There are currently many participating non-VA hospitals and the NSQIP helps pinpoint areas of improvement in individual hospitals and in surgical programs as a whole.

Reference:

Rowell KS, Turrentine FE, Hutter MM, et al. Use of national surgical quality improvement program data as a catalyst for quality improvement. J Am Coll Surg. 2007; 204(6):1293-1300.

1B05

Key word: Diagnosis of Lymphocele in Deceased Donor Kidney Transplant

Author: Robert A. Meguid, MD, MPH

Editors: Robert A. Montgomery, MD, DPhil, FACS, and Dorry L. Segev, MD, PhD

Four weeks after a deceased donor kidney transplant, the recipient returns to the emergency department with bilateral lower-extremity edema. In spite of normal fluid intake, he reports that he has had minimal urine output over the past 18 hours. Serum creatinine is now elevated to 1.4 mg/dL from 1.0 mg/dL postoperatively. After failure to respond to a fluid challenge, an ultrasound is obtained. This reveals good perfusion, minimal hydronephrosis, and a 3- × 4- × 6-cm hypoechoic mass adjacent to the renal pelvis of the allograft. What is the most likely cause of the patient’s oliguria?

Compressive hematoma

Lymphocele formation

Renal artery stenosis

Renal artery thrombosis

Ureteroneocystostomy stenosis

View Answer

Answer: (B) Lymphocele formation

Rationale:

The most common cause of urinary obstruction from extrinsic compression of the ureter at this point after a transplant is a lymphocele. The lymphocele forms in the retroperitoneal space at the iliac fossa developed for the implantation of the allograft, due to disruption of the tiny lymphatics that surround the recipient’s external iliac artery and vein, and the inability of this space to absorb lymph (as opposed to, e.g., the peritoneal cavity). Postoperatively, as lymph collects in the perinephric space, pressure is exerted on the ureter, resulting in obstruction. Clinically this manifests as decreased urine output. Ultrasound reveals the offending fluid collection as a hypoechoic mass with accompanying hydronephrosis. Percutaneous drainage may be attempted and, if unsuccessful, creation of a peritoneal window laparoscopically is the preferred treatment.

Ureteroneocystostomy stenosis, or stenosis at the ureterovesical anastomosis, is a technical complication that occurs early in the postoperative course. To minimize the likelihood of this occurring, a stent may be placed intraoperatively through the anastomosis. Hydronephrosis would be expected, but no fluid collection.

Vascular compromise usually occurs within the first few hours to days after a kidney transplant. Events leading to this include renal artery or vein thrombosis, arterial dissection, and pseudoaneurysm formation. Hemorrhage, possibly from one of the vascular anastomoses, can result in pooling of blood around the ureter and subsequent obstruction, but this is almost always a very early complication.

Renal artery stenosis usually occurs months to years after transplantation, and presents with oliguria, hypertension, and rising serum creatinine levels.

References:

Fischer AC. Transplant immunology and solid organ transplantation. In: Fleischer KJ, ed. Advanced Surgical Recall. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1995: 1150.

Freise C, Stock P. Renal transplantation. In: Mulholland MW, Lillemoe KD, Doherty GM, Maier RV, Upchurch GR, eds. Greenfield’s Surgery: Scientific Principles & Practice. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011.

1B06

Key word: Treatment of CO2 Embolus during Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy

Author: Robert A. Meguid, MD, MPH

Editors: Thomas H. Magnuson, MD, and Kenzo Hirose, MD, FACS

While visualizing the gallbladder during an elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy, the anesthesiologist informs you that the patient has a heart rate of 130, and a dropping blood pressure. What is the FIRST step in management?

Decrease insufflation pressure

Give inotropes for blood pressure

Give IV fluids

Position the patient in the left lateral decubitus position

Stop insufflation

View Answer

Answer: (E) Stop insufflation

Rationale:

Tachycardia and hypotension shortly after insufflation for laparoscopy can be related to decreased venous return to the right heart, tension pneumothorax, or CO2 embolism. The first step is to stop insufflation and immediately release the pneumoperitoneum.

In the event of a gas embolus, examination of the patient will reveal a “mill wheel” murmur due to air bubbling in the right ventricle, as well as jugular venous distention and hypoxemia. A tension pneumothorax is indicated by tracheal deviation and absence of breath sounds unilaterally will be present. If visible, the diaphragm may be bulging into the peritoneal space.

Further treatment of gas embolism involves positioning the patient in the left lateral decubitus position to limit the gas bubbles to the right atrium and ventricle, hyperventilation, and if present, using a central venous access to extract the gas via catheter.

Decreasing the insufflation pressure does not rectify the life-threatening problem, but will perpetuate it. Insufflation must be stopped immediately. Giving IV fluids, while appropriate when the cause of shock is relative hypovolemia, will not treat the cause of the problem in this example, nor the problem of a functional pulmonary artery or coronary artery obstruction itself. While giving inotropes may increase the blood pressure, it will not correct the life-threatening problem. Insufflation must be stopped immediately.

References:

Bayne S, Blackbourne LH. Laparoscopy. In: Fleischer KJ, ed. Advanced Surgical Recall. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 1995:315.

Moore FA, Moore EE. Trauma resuscitation. In: Souba WW, Fink MP, Jurkovich GJ, Kaiser LR, Pearce WH, Pemberton JH, Soper NJ, eds. ACS Surgery: Principles and Practice, 4th ed. New York, NY: WebMD; 2004:855-856.

1B07

Key word: Characteristics of Local Anesthetic Toxicity

Author: Robert A. Meguid, MD, MPH

Editor: Nicole M. Chandler, MD

A 26-year-old male is undergoing a nerve block for an outpatient orthopedic procedure on his left ankle. During injection of the superficial fibular nerve with lidocaine, he complains of tingling around his mouth and lips. What other symptom would be consistent with lidocaine toxicity?

Hallucinations

High fever

Muscle rigidity

Peripheral paralysis

Skin ischemia

View Answer

Answer: (A) Hallucinations

Rationale:

Local anesthetics are a class of drugs that produces effect by temporarily blocking nerve conduction by binding to neuronal sodium channels. The progression of action of local anesthetics on nerve function is as follows: Blockade of autonomic transmission, blockade of sensory transmission, and blockade of motor transmission.

The toxicity of local anesthetics is dependent on the site of injection and the rate of absorption. Inadvertent intravascular injection of a local anesthetic will produce signs of toxicity with much smaller doses. The progression of signs of local anesthesia toxicity and overdose are as follows: Perioral paresthesias, visual and auditory hallucinations, sedation, unconsciousness, seizures, respiratory depression, cardiac arrhythmias, and cardiovascular collapse. The best techniques to prevent toxicity from local anesthetics are to aspirate before injecting to avoid intravascular injection and knowledge of the maximal safe dose to be injected.

The maximum dose of lidocaine is 5 mg/kg of body weight, and increases to 7 mg/kg of body weight when epinephrine (1:100,000) is included in the formulation. The addition of epinephrine slows absorption as a result of vasoconstriction and also decreases the likelihood of toxicity, however, may induce local ischemia due to vasoconstriction. Bupivacaine’s maximum dose is 2.5 mg/kg of body weight. Treatment of lidocaine toxicity includes supportive measures such as oxygen therapy and airway support and treatment of seizures if necessary. Cardiac toxicity may require inotropic and chronotropic agents or in extreme cases, temporary cardiopulmonary bypass. Cardiovascular toxicity from bupivacaine may be particularly difficult to treat.

References:

Kheterpal S, Rutter TW, Tremper KK. Anesthesiology and pain management. In: Mulholland MW, Lillemoe KD, Doherty GM, Maier RV, Upchurch GR, eds. Greenfield’s Surgery: Scientific Principles & Practice. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011.

Sherwood ER, Williams CG, Prough DS. Chapter 16: Anesthesiology principles, pain management, and conscious sedation. In: Townsend CM, Beauchamp RD, Evers BM, Mattox KL, eds. Sabiston Textbook of Surgery: The Basis of Modern Surgical Practice. 19th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2012:389-417.

1B08

Key word: Etiology of Recurrence in Laparoscopic Hernia Repair

Author: Susanna M. Nazarian, MD, PhD

Editor: Frederick E. Eckhauser, MD, FACS

An obese woman who underwent a transabdominal hysterectomy 10 years ago presents for an elective ventral hernia repair. She undergoes hernia repair via a laparoscopic approach, to which she responds well initially. However, she develops a recurrent bulge 2 months later and presents to your office for counseling. What is the most common reason for recurrence after laparoscopic ventral hernia repair?

Failure of suture material or tacks

Inadequate dissection of the fascial defect

Separation of the mesh from the abdominal wall

Seroma formation

Unrecognized defect

View Answer

Answer: (C) Separation of the mesh from the abdominal wall

Rationale:

Incisional abdominal hernias are attributed to poor technique, rough handling of tissues, closure of the wound under tension, and infection. In addition, patient comorbidities such as obesity, smoking, nutritional deficiencies, and pulmonary disease have been identified as contributing causes.

In a study of 121 laparoscopic hernia repairs published in 2005, Perrone and colleagues found a hernia recurrence rate of 9.3%. They concluded that the most common etiology of recurrence was separation of mesh from the posterior abdominal fascia, thereby allowing the intestine to interpose between the mesh and the wall. Some techniques employed to combat this problem include ensuring adequate mesh overlap of a defect, fixation of mesh, and adequate dissection. Although seroma is the most common complication following laparoscopic ventral hernia repair, it does not necessarily contribute to recurrence. The laparoscopic approach is well suited to patients with a “Swiss cheese” abdomen as small fascial defects are more likely to be recognized with the superior visualization. A more recent pooled data analysis of all Englishlanguage reports on laparoscopic ventral hernia repair from 1996 to 2006 measured the hernia recurrence rate for laparoscopic rates at 4.3%.

References:

Fitzgibbons RJ, Cemaj S, Quinn TH. Abdominal wall hernias. In: Mulholland MW, Lillemoe KD, Doherty GM, Maier RV, Upchurch GR, eds. Greenfield’s Surgery: Scientific Principles & Practice. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011.

Perrone JM, Soper NJ, Eagon JC, et al. Perioperative outcomes and complications of laparoscopic ventral hernia repair. Surgery. 2005;138(4):708-715.

Pierce RA, Spitler JA, Frisella MM, et al. Pooled data analysis of laparoscopic vs. open ventral hernia repair: 14 years of patient data accrual. Surg Endosc. 2007;21(3):378-386.

1B09

Key word: Tetanus Prophylaxis

Author: Robert A. Meguid, MD, MPH

Editor: Nicole M. Chandler, MD

A 21-year-old male is brought to the trauma bay after sustaining a superficial stab wound to the left shoulder. He reports that he received his full series of shots as a child and received his last tetanus booster shot when he was 15. What should he receive for his tetanus prophylaxis?

Amoxicillin 500-mg PO TID

Nothing

Tetanus immune globulin (TIG) 250-units IM

Tetanus toxoid (dT) 0.5-mL IM

Tetanus toxoid (dT) 0.5-mL IM and TIG 250-units IM

View Answer

Answer: (D) Tetanus toxoid (dT) 0.5-mL IM

Rationale:

Active tetanus immunization is obtained by administration of three doses of tetanus toxoid, given at age 2, 4, and 6 months, followed by two additional doses (“boosters”) of tetanus toxoid, given at age 1 and 5 years. Subsequent “booster” doses of tetanus toxoid are given at 10-year intervals for life. The Center for Disease Control recently provided new recommendations for tetanus prophylaxis, principally because of outbreaks of pertussis. As of 2005, there are two tetanus/diphtheria/acellular pertussis vaccines (Tdap) available for adolescents, one of which is available for adults as well. The CDC-based Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) now recommends that adolescents receive a one-time boost of Tdap for booster immunization rather than Td for booster immunization if they have completed the DTP/DTaP vaccination series and have not yet received their booster. The preferred age for Tdap vaccination is 11 to 12 years.

Passive TIG provides protective levels of antibodies for 3 to 4 weeks and the adult dose is 250-units IM. Tetanus toxoid (dT) 0.5-mL IM is the standard booster.

Natural immunity to tetanus does not occur in the United States. Forty percent of cases of tetanus are not associated with any history of injury, and the mortality rate is 20% to 40%. Universal recommendations from the CDC for tetanus prophylaxis depend on the wound characteristics and the patient’s immunization status. Characteristics of tetanus-prone wounds include penetrating injuries greater than 1 cm in depth, wounds greater than 6 hours old, contaminated or infected wounds, and ischemic or denervated injuries.

The principles for tetanus prophylaxis of the acute wound are as follows.

For patients with acute soft tissue injuries (regardless of suspicion for tetanus) who have not been immunized, a tetanus toxoid booster is required, along with follow-up to complete the series.

For patients with a tetanus-prone wound who have not completed a primary immune series, administer TIG 250 units.

For patients who have completed a primary immune series, a booster is given if the last dose was >5 years prior (for tetanus-prone wound) or >10 years prior (for a nontetanus-prone wound).

Patients with a contraindication to tetanus toxoid must be managed with TIG alone.

Therefore, the correct answer is “tetanus toxoid (dT) 0.5-mL IM” as the patient has completed his primary immunizations and received his last booster 6 years ago.

References:

Adams CA, Heffernan DS, Cioffi WG. Chapter 47: Wounds, bites, and stings. In: Mattox KL, Moore EE, Feliciano DV, eds. Trauma. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013. http://www.accesssurgery.com/content.aspx?aID= 56897521. Accessed March 20, 2013.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations for postexposure interventions to prevent infection with hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, or human immunodeficiency virus, and tetanus in persons wounded during bombings and similar mass-casualty events—United States, 2008. MMWR 2008; 57 (No. RR-6).

Howdieshell TR, Heffernan D, Dipiro JT, et al. Surgical infection society guidelines for vaccination after traumatic injury. Surg Infect. 2006;7(3):275-303.

1B10

Key word: Difference in ARDS versus Ventilator-associated Pneumonia

Authors: Justin B. Maxhimer, MD, and Susanna M. Nazarian, MD, PhD

Editor: Elliott R. Haut, MD, FACS

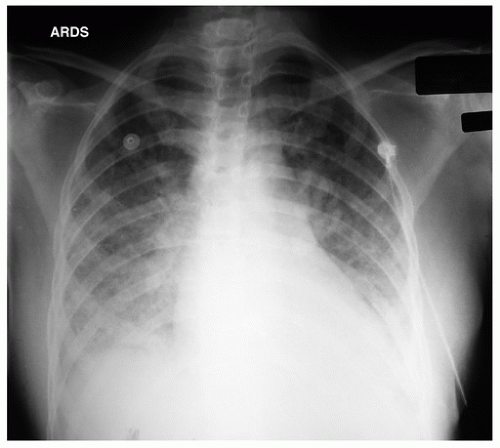

A 56-year-old male is ventilator dependent due to an open abdomen secondary to trauma. On the third day following his injury, he develops hypoxemia and tachypnea requiring an increase of the fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) and positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP). His partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood (PaO2) increases minimally with these changes. Plain chest radiograph shows bilateral infiltrates and pulmonary artery occlusion pressure is 16 mm Hg. Which combination of features would support a diagnosis of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) over ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP)?

PaO

2/FiO

2 ratio <200 mm Hg

Pulmonary artery occlusion pressure ≥18 mm Hg

Temperature 38.3°C, WBC = 12, minimal pleural effusion, increased protein on bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), infiltrates not seen on chest radiograph

Temperature 38.5°C, WBC = 16, no effusions, increased protein on BAL

Temperature 38.7°C, WBC = 14, pleural effusions, increased protein on BAL

View Answer

Answer: (D) Temperature 38.5°C, WBC = 16, no effusions, increased protein on BAL

Rationale:

ARDS is sudden, life-threatening lung failure. This diffuse inflammatory process leads to leaky capillaries and proteinaceous exudate accumulates in alveoli. The alveoli subsequently collapse and gas exchange ceases in the obliterated air spaces. Hypoxemia ensues requiring mechanical ventilation or some other form of assisted breathing. ARDS is a syndrome, not a specific disease, and a variety of underlying conditions can lead to the end-organ damage. Etiologies of ARDS range from trauma to sepsis, from burns to major surgery.

The initial lung injury of ARDS is poorly understood. Animal studies suggest that activated white blood cells and platelets accumulate in capillaries, the interstitium, and airspaces, leading to the release of prostaglandins, toxic O2 radicals, proteolytic enzymes, and other mediators such as tumor necrosis factor and interleukins. These injure cells, promote inflammation and fibrosis, and alter bronchomotor tone and vasoreactivity.

Early diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion aroused by the onset of dyspnea in settings that predispose to ARDS. The American-European Consensus Committee developed the first consensus definition of ARDS in 1994, which was recently revised in 2011 to the Berlin Definition: (1) Onset within 1 week of a clinical insult or new or worsening respiratory symptoms, (2) bilateral opacities on CXR or CT not

explained by effusions, lobar collapse, or nodules, (3) respiratory failure not explained by cardiac failure or fluid overload (can determine using PA catheter, echocardiography, etc.), (4) oxygenation difficulty as defined by PaO

2/FiO

2 ratio (with minimum PEEP 5 cm H

2O): 200 mm Hg < PaO

2/FiO

2 ≤300 mm Hg (mild), 100 mm Hg < PaO

2/FiO

2 ≤ 200 mm Hg (moderate), or 100 mm Hg < PaO

2/FiO

2. Of note, the term acute lung injury was removed from the definition.

It should be noted that these defining characteristics for ARDS diagnosis do not help in distinguishing it from VAP. Indeed, VAP may be the driving force behind the development of ARDS. Both ARDS and VAP patients may have PaO2/FiO2 ratio <300 mm Hg. A more reliable method for confirming ARDS is BAL. The BAL of ARDS patients is characterized by high neutrophil percentage (up to 80%) and large protein content. More specifically, a ratio of protein in BAL to that in serum >0.7 is consistent with ARDS. While BAL is more reliable in establishing a diagnosis of ARDS than the consensus diagnostic criteria, it is an invasive procedure that may temporarily further compromise the patient’s respiratory status.

Answer (B) is an example of a patient who is more likely to have VAP. VAP is defined as nosocomial pneumonia in a patient on mechanical ventilatory support (by endotracheal tube or tracheostomy) for ≥48 hours. VAP is characterized by the appearance of a new or progressive pulmonary infiltrate and effusions, fever, leukocytosis, and purulent tracheobronchial secretions; however, these criteria are nonspecific. The patient in example (D) should be worked up for a pulmonary embolism.

References:

ARDS Definition Task Force, Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: The Berlin definition. JAMA. 2012;307(23):2526-2533.

Bernard GR, Artigas A, Brigham KL, et al. Report of the American-European Consensus conference on acute respiratory distress syndrome: Definitions, mechanisms, relevant outcomes, and clinical trial coordination. J Crit Care. 1994;9(1):72-81.

Marino PL. “Acute respiratory distress syndrome” and “Principles of mechanical ventilation.” The ICU Book. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2007: 419-471.

Markowicz P, Wolff M, Djedaïni K, et al. Multicenter prospective study of ventilator-associated pneumonia during acute respiratory distress syndrome. Incidence, prognosis, and risk factors ARDS Study Group. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161(6):1942-1948.

Mayhall CG. Ventilator-associated pneumonia or not? Contemporary diagnosis. Emerg Infect Dis. 2001;7(2):200-204.

1B11

Key word: Treatment of Incarcerated Inguinal Hernia

Author: Justin B. Maxhimer, MD

Editor: Frederick E. Eckhauser, MD, FACS

A 2-year-old boy is brought to the emergency department by his mother. She reports that he has been inconsolable for the past 24 hours and has refused his feeds. Upon further questioning, the physician finds that the child has vomited twice and has not had a bowel movement. Examination reveals a slightly distended and diffusely tender abdomen, especially in the inguinal area, without signs of peritonitis. What should be your first step?

Arrange for immediate groin exploration in the operating room without attempting manual reduction

Elevation of the child’s lower extremities with a pillow, followed by an attempt at manual reduction

Emergent exploratory laparotomy

Apply ice pack to the affected area

Overnight inpatient observation

View Answer

Answer: (B) Elevation of the child’s lower extremities with a pillow, followed by an attempt at manual reduction

Rationale:

Most children with an inguinal hernia present with a history of intermittent swelling in the inguinal region, which in boys, may extend to the scrotum. The presence of a mass or thickening in the inguinal canal or at the level of the internal inguinal ring is diagnostic of an inguinal hernia. The swelling is usually nontender and readily reducible with gentle pressure.

Most inguinal hernia repairs in full-term healthy infants and older children may be performed electively in an outpatient surgical setting. Infants less than 6 to 12 months of age, particularly former premature babies, are at greater risk for incarceration. Repair in these babies should be carried out as soon as convenient, and preferably within 1 week of the diagnosis. An overnight hospitalization after surgery may be necessary for postoperative apnea monitoring in these former premature babies and infants under 6 to 12 months of age as well as other children with special needs (a group which includes those with ventriculo-peritoneal shunts, cardiopulmonary disease, etc.).

A hernia is considered incarcerated when the contents of the hernia sac are trapped in the inguinal canal and cannot be easily reduced into the abdominal cavity. Incarceration of an inguinal hernia is most common in the first year of life. The incidence falls with age, but never disappears entirely and must be considered with hernias at any age. An incarcerated hernia usually presents as a firm swelling in the inguinal region (possibly extending to the scrotum) that is tender to palpation and does not readily reduce with pressure. The child may be extremely irritable and unwilling to eat. Intestinal obstruction, with abdominal distention and vomiting, may be present. The differential diagnosis includes inguinal lymphadenitis, torsion of the testicle, and acute hydrocele. Even with an incarcerated hernia, the affected groin may become edematous and a reactive hydrocele may evolve.

Elevation of the child’s legs can help encourage spontaneous reduction but is just a temporizing maneuver. Ice packs should be avoided in both infants and children. Reduction of an incarcerated hernia should be attempted and can be achieved in the majority of cases. Sedation (with a short-acting benzodiazepine or opiate narcotic) and firm, steady pressure over the hernia (for several minutes and up to half an hour) may be necessary. If reduction is successful, the child should be admitted to the hospital and surgical correction planned for 24 to 48 hours later (when some of the initial edema has resolved). The patient should not be discharged since the risk of recurrence is very high. If signs of strangulation are present, no attempt at reduction should be made, and emergency surgical intervention should be undertaken. Under these circumstances, resection of a segment of ischemic bowel may be necessary.

Reference:

Sato TT, Oldham KT. Pediatric abdomen. In: Mulholland MW, Lillemoe KD, Doherty GM, Maier RV, Upchurch GR, eds. Greenfield’s Surgery: Scientific Principles & Practice. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011.

1B12

Key word: Etiology of Hyponatremia in Pancreatitis

Author: Susanna M. Nazarian, MD, PhD

Editor: Martin A. Makary, MD, MPH

A 45-year-old woman with a history of gallstones is admitted to the intensive care unit after diagnosis with acute pancreatitis with hemodynamic instability. Her admission laboratory values were remarkable for a number of abnormalities, including hyponatremia, hyperamylasemia, hyperlipasemia, and hyperlipidemia. What is the etiology of hyponatremia in pancreatitis?

Hypoalbuminemia

Pseudohyponatremia

Renal failure

Salt wasting

Syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone (SIADH)

View Answer

Answer: (B) Pseudohyponatremia

Rationale:

Pseudohyponatremia in pancreatitis derives from the method of sodium measurement. In pancreatitis with hyperlipidemia, circulating lipids draw water into the intravascular compartment, leading to relative hyponatremia. Plasma exchange can be used to remove lipids from the circulation. Aggressive overcorrection of pseudohyponatremia with hyperosmolar fluids can lead to dangerous electrolyte disturbances.

Patients with acute pancreatitis are subject to numerous other disturbances in their laboratory values. The primary pancreatic enzymes of amylase and lipase are increased three times higher than baseline, although amylase levels may return to baseline within 3 to 5 days given its short half-life. Patients with gallstones as the etiology of their disease may have laboratory values reflecting inflammation or obstruction of the biliary tract. Hypercalcemia is a source of pancreatitis, while hypocalcemia can result from the action of leaking pancreatic enzymes during an attack of pancreatitis.

References:

Gold JS, Whang EE. Acute pancreatitis. In: Mulholland MW, Lillemoe KD, Doherty GM, Maier RV, Upchurch GR, eds. Greenfield’s Surgery: Scientific Principles & Practice. 5th ed.

Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011. Howard JM, Reed J. Pseudohyponatremia in acute hyperlipemic pancreatitis. A potential pitfall in therapy. Arch Surg. 1985;120(9):1053-1055.

1B13

Key word: Treatment of Hypotension after Removal of Pheochromocytoma

Author: Robert A. Meguid, MD, MPH

Editor: Frederick E. Eckhauser, MD, FACS

A 42-year-old woman is in the intensive care unit immediately following removal of a left adrenal pheochromocytoma. Her blood pressure is 80/40 mm Hg. The most appropriate treatment of the patient’s hypotension is:

Epinephrine

IV bolus of lactated Ringer solution

Methylprednisolone

Phenoxybenzamine

Phenylephrine

View Answer

Answer: (B) IV bolus of lactated Ringer solution

Rationale:

Hypotension after removal of a pheochromocytoma is due to hypovolemia. This should have been prevented by appropriate fluid resuscitation prior to operation. Occurring postoperatively, it is most appropriately treated with aggressive IV fluid administration.

Patients with pheochromocytomas are hypertensive, with increased vasomotor tone, and prone to cardiac arrhythmias. Preoperative preparation of patients with pheochromocytomas begins with α-adrenergic blockade 1 to 3 weeks prior to surgery. Phenoxybenzamine is the preferred long-acting agent. In conjunction with this pharmacologic treatment, fluid resuscitation should be given to fill the re-expanding vascular compartment. Typically patients should gain significant weight (fluid) during this period of preoperative preparation, and failure to do so may foreshadow postoperative hypotension. Once α-adrenergic blockade has been achieved (as measured by normal orthostatic changes in blood pressure), β-adrenergic blockade should be initiated. This is achieved with propranolol, started 48 hours prior to surgery. Of note, β-adrenergic blockade should never be instituted prior to adequate a-adrenergic blockade and fluid resuscitation, as the ensuing unopposed α-adrenergic activity may result in worsened vasoconstriction leading to myocardial infarction, hypertensive crisis, or pulmonary edema.

Treatment of the hypotensive patient status post removal of pheochromocytoma with phenoxybenzamine will result in further vasodilation and will worsen hypotension. While epinephrine and phenylephrine may ameliorate this patient’s hypotension transiently, neither of them will treat the underlying cause—namely hypovolemia. Phenylephrine is a dedicated α1-agonist, while epinephrine acts on α1-, β1-, and β2-adrenergic receptors.

As with any other operation, bleeding must be considered as the cause of hypotension following pheochromocytoma removal.

References:

Hodgett S, Brunt LM. Adrenalectomy. In: Cance WG, Jurkovich GJ, Napolitano LM, eds. ACS Surgery: Principles and Practice. New York, NY: WebMD; 2011.

Silberfein E, Perrier ND. Management of pheochromocytomas. In: Cameron JL, ed. Current Surgical Therapy. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby; 2011:579-584.

1B14

Key word: Initial IV Fluid in Treatment of Dehydration

Author: Nikiforos Ballian, MBBS

Editor: Nicole M. Chandler, MD

A 7-week-old boy is referred with a 3-day history of projectile nonbilious vomiting. He appears dehydrated and, on abdominal examination, an olive-shaped epigastric mass is palpable. The most appropriate initial IV fluid regimen for resuscitation is:

2% sodium chloride

5% dextrose

Lactated Ringer

Normal saline

Normal saline + 20-mmol/L potassium chloride

View Answer

Answer: (D) Normal saline

Rationale:

Hypertrophic pyloric stenosis (HPS) occurs in 2 to 4 per 1,000 live births and is more common in males. It is characterized by thickening of the pyloric smooth muscle, which is palpable as an abdominal “olive-like” mass, pathognomonic for this condition. HPS presents between 2 and 12 weeks of age with projectile nonbilious vomiting that leads to dehydration with hyponatremia, hypokalemia, hypochloremia, and metabolic alkalosis.

Preoperative correction of dehydration and electrolyte deficits is critical. Normal saline should be used without added potassium until an adequate urine output has been restored, to prevent rapid changes in serum potassium. Hypotonic solutions such as 5% dextrose should never be used to correct dehydration in children as they can cause lethal hyponatremia. There is no role for lactated Ringer in resuscitating alkalotic chloride-depleted patients. Hypertonic sodium chloride is used to correct severe symptomatic hyponatremia and/or for rapid expansion intravascular volume. Initial resuscitation with normal saline is the most appropriate option to address the fluid and electrolyte deficiencies of HPS patients.

References:

Aspelund G, Langer JC. Current management of hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2007;16(1):27-33.

Jackson J, Bolte RG. Risks of intravenous administration of hypotonic fluids for pediatric patients in ED and prehospital settings: Let’s remove the handle from the pump. Am J Emerg Med. 2000;18(3):269-270.

Miozzari HH, Tonz M, von Vigier RO, et al. Fluid resuscitation in infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. Acta Paediatr. 2001;90(5):511-514.

To T, Wajja A, Wales PW, et al. Population demographic indicators associated with incidence of pyloric stenosis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(6):520-525.

Warner BW. Pediatric surgery. In: Townsend CM, Beauchamp RD, Evers BM, Mattox KL, eds. Sabiston Textbook of Surgery. 17th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2004:2097-2134.

1B15

Key word: Diagnosis of Thrombosis of Hepatic Artery after Liver Transplantation

Author: Robert A. Meguid, MD, MPH

Editor: Andrew M. Cameron, MD, PhD

A 45-year-old female is in the SICU 2 days postoperative from an orthotopic liver transplant for primary biliary cirrhosis. The patient’s condition has rapidly deteriorated, with signs consistent with fulminant hepatic failure. Ultrasound of the graft is most likely to reveal which of the following?

Hepatic artery thrombosis

Hepatic vein thrombosis

Inferior vena cava stenosis

Portal vein stenosis

Portal vein thrombosis

View Answer

Answer: (A) Hepatic artery thrombosis

Rationale:

Hepatic artery thrombosis can occur early in the postoperative period. This is manifested as fulminant hepatic failure; treatment is retransplantation. Delayed hepatic artery thrombosis can result in necrosis of the bile duct, as the biliary anastomosis receives its blood supply from the hepatic artery.

Less common than hepatic artery thrombosis, portal vein thrombosis presents with liver dysfunction in the immediate postoperative period. Treatment is reoperation with thrombectomy. Delay in the development of portal vein thrombosis or stenosis results in portal venous hypertension. Symptoms include ascites, variceal bleeding, and splenomegaly. Treatment of thrombosis is operative; however, stenosis may be treated with angioplasty.

Even more uncommon, hepatic vein thrombosis and IVC stenosis may result in Budd-Chiari syndrome. Again, operative treatment is indicated. IVC stenosis may occasionally be dilated and stented.

References:

Crawford JM. The liver and the biliary tract. In: Cotran RS, Kumar V, Collins T, eds. Robbins Pathologic Basis of Disease. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders. 1999: 883-884.

Martin P, Rosen HR. Liver transplantation. In: Feldman M, Friedman LS, Brandt LJ, eds. Sleisenger and Fordtran’s Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2006. Online Edition.

1B16

Key word: Diagnostic Test for Soft Tissue Sarcoma of the Thigh

Authors: Robert A. Meguid, MD, MPH, and Susanna M. Nazarian, MD, PhD

Editor: Frank J. Frassica, MD

A 55-year-old man presents with a firm mass on his left thigh, which he noticed recently after bumping into a chair. The mass is painless, not discolored, and 5 cm in diameter. What is the next diagnostic test you should perform?

Excisional biopsy

Fine-needle aspiration

Incisional biopsy

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan

Wide excision with 2-cm margins

View Answer

Answer: (D) Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan

Rationale:

The lesion of concern for an extremity mass is a soft tissue sarcoma. The area most commonly involved by sarcomas is the thigh. While there is no correlation of development of soft tissue sarcomas with trauma, attention is often called to the presence of a mass after trauma to that area.

Imaging is the first step in evaluation of a presumed sarcoma, and MRI offers superior soft tissue resolution without radiation exposure. Removal of the mass without prior imaging should never be performed. If the imaging studies suggest a soft tissue sarcoma, either a needle biopsy (fine-needle or core) or an incisional biopsy should be performed. Excisional biopsy would be a major error in treatment, as resection of high-grade soft tissue sarcoma with multiple positive margins greatly increases the risk of local failure. In addition, excisional biopsy risks infection, wound-healing problems, and contamination of major neurovascular structures, thus compromising definitive therapy.

Staging studies include a CT scan of the chest and a chest radiograph.

Reference:

Frassica FJ, Khanna JA, McCarthy EF. The role of MR imaging in soft tissue tumor evaluation: Perspective of the orthopedic oncologist and musculoskeletal pathologist. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2000;8(4):915-927.

1B17

Key word: Conditions Associated with Normal Anion Gap Acidosis

Authors: Kelly Olino, MD, and Susanna M. Nazarian, MD, PhD

Editor: Elliott R. Haut, MD, FACS

A 42-year-old man with marked ascites is being treated with lactulose for hepatic encephalopathy secondary to alcoholic cirrhosis. What is the most likely acid-base abnormality found in this patient?

Anion gap metabolic acidosis

Metabolic alkalosis

Normal anion gap metabolic acidosis

Respiratory acidosis

Respiratory alkalosis

View Answer

Answer: (C) Normal anion gap metabolic acidosis

Rationale:

Metabolic acidosis is classified as either elevated anion gap metabolic acidosis or normal anion gap (or hyperchloremic) metabolic acidosis. The anion gap is calculated by subtracting the sum of serum concentrations of the anions, Cl– and HCO3–, from the sum of the cations, Na+ and K+: Anion gap = ([Na+] + [K+]) – ([Cl–] + [HCO3–]). The normal anion gap ranges from 14 to 18. For simplicity, some experts do not use the serum potassium value in the calculation and thus the normal anion gap range would be 10 to 14. The differentiation of metabolic acidosis into anion gap or normal anion gap categories assists in the formulation of a differential diagnosis and in treatment.

Patients with hepatic encephalopathy are likely to be treated with two medications that are known to cause a normal anion gap metabolic acidosis: Lactulose and spironolactone. Lactulose causes an osmotic diarrhea leading to bicarbonate losses. Spironolactone is an aldosterone antagonist, limiting potassium and hydrogen ion excretion in the distal renal tubules and contributing to hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis.

Generally speaking, there are a number of potential causes of normal anion gap metabolic acidosis. Bicarbonate may be lost through the gastrointestinal tract (nasogastric tube suctioning, small bowel drainage, diarrhea) or kidneys (renal tubular acidosis, ureteroileostomy). Iatrogenic causes include improper balancing of electrolytes in total parenteral nutrition (TPN) formulations or administration of excessive amounts of normal saline, potassium chloride, or ammonium chloride. Medications such as ammonium chloride, lysine, or arginine hydrochloride and carbonic anhydrase inhibitors may also induce metabolic acidosis. Primary hyperparathyroidism and aldosterone deficiency or insensitivity are other causes of metabolic acidosis.

References:

Andreoli TE, Abul-Ezz SR. Fluid and electrolyte disorders. In: Andreoli TE, Carpenter CCJ, Griggs RC, Loscalzo J, eds. Cecil Essentials of Medicine. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders Company; 2001:238-252.

Gabow PA, Moore S, Schrier RW. Spironolactone-induced hyperchloremic acidosis in cirrhosis. Ann Intern Med. 1979;90(3):338-340.

Gauthier PM, Szerlip HM. Metabolic acidosis in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Clin. 2002;18:289-308.

Slonim AD. Consider excess chloride as a cause of an unexplained non-anion-gap metabolic acidosis. In: Marcucci L, Martinez EA, Haut ER, Slonim AD, Suarez JI, eds. Avoiding Common ICU Errors. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007:429-430.

1B18

Key word: Treatment of 0.6-mm Melanoma of the Forearm

Authors: Robert A. Meguid, MD, MPH, and Susanna M. Nazarian, MD, PhD

Editors: Charles M. Balch, MD, FACS, and Lisa K. Jacobs, MD

A 76-year-old man presents with a lesion on the left forearm suspicious for melanoma. Biopsy confirms a melanoma of 0.6 mm thickness. What margin around the lesion do you need to take during excision to minimize the likelihood of recurrence?

None

5 mm

1 cm

2 cm

Greater than 2 cm

View Answer

Answer: (C) 1 cm

Rationale:

The Melanoma Task Force of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) revised the melanoma staging system in 2003. Please see the explanation for question M30 for detailed discussion of this TNM-based system. A patient with a localized invasive melanoma is either Stage I or II, depending on the thickness of the lesion (Breslow thickness).

Numerous clinical trials have revised the former practice of excision of all melanomas with a 4- to 5-cm margin. Current recommendations for surgical margin include the following.

Normally excision is performed using an elliptical excision with primary closure. Cosmesis is improved by using a 3:1 ratio of length:width in creating the ellipse. Excision should extend to the underlying muscle fascia, but not through it. In extremely obese patients, the excision depth should extend at least to the superficial fascia.

T1b, T2, T3, and T4 melanomas should have lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymph node biopsy. A completion radical lymph node dissection should be performed when the sentinel lymph contains metastatic disease or in patients with clinically apparent nodal involvement when the diagnosis is confirmed by fine-needle aspiration. Stage III disease usually warrants systemic therapy.

Of note, additional factors associated with a worsened outcome include male sex, ulceration of the primary melanoma, mitotic rate >1/mm2 and location on the head or trunk.

References:

Balch CM, Buzaid AC, Soong S-J, et al. Final version of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system for cutaneous melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2001; 19(16):3635-3648.

Balch CM, Soong SJ, Gershenwald JE, et al. Prognostic factors analysis of 17,600 melanoma patients: Validation of the American Joint Committee on Cancer Melanoma Staging System. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(16):3622-3634.

Gershenwalk JE, Balch CM, Soong S-J, et al. Prognostic factors and natural history. In: Balch CM, Houghton AN, Sober AJ, Soong S-J, eds. Cutaneous Melanomas. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Quality Medical Publishing; 2003:25-54.

Ross MI. New American Joint Commission on Cancer staging system for melanoma: Prognostic impact and future directions. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2006;15(2):341-352.

Ross MI, Balch CM, Cascinelli N, et al. Excision of primary melanoma. In: Balch CM, Houghton AN, Sober AJ, Soong S-J, eds. Cutaneous Melanomas, 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Quality Medical Publishing; 2003:218-222.

Veronesi U, Cascinelli N, Adamus J, et al. Thin stage I primary cutaneous malignant melanoma: Comparison of excision with margins of 1 or 3 cm. N Engl J Med. 1988;318(18): 1159-1162.

1B19

Key word: Antibiotic Treatment of Emphysematous Cholecystitis

Author: Bonnie E. Lonze, MD, PhD

Editor: Martin A. Makary, MD, MPH

A 42-year-old diabetic woman presents to the emergency department complaining of nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. She had been in her usual state of health until the prior day when the symptoms began. Her temperature is 38°C and her white blood cell count is 17,000. Initial workup includes a right upper quadrant ultrasound that is negative for stones but is suggestive of air within the lumen of the gallbladder. The most appropriate initial antibiotic choice for this patient would be:

Intravenous amikacin

Intravenous ampicillin/sulbactam

Intravenous cefazolin

Intravenous clindamycin

Intravenous piperacillin/tazobactam

View Answer

Answer: (E) Intravenous piperacillin/tazobactam

Rationale:

Emphysematous cholecystitis is a particularly severe variant of acute cholecystitis which is associated with a significantly greater mortality and morbidity when compared to other types of acute cholecystitis. In emphysematous cholecystitis, the infection is caused by a gas-forming bacterium. Radiographic diagnosis is made via ultrasound or computed tomography, and characteristic radiographic findings in this disease, namely gas within the gallbladder lumen, gallbladder wall, and occasionally, bile ducts. The incidence of gallbladder perforation is approximately fivefold greater in emphysematous cholecystitis. There is a higher incidence of emphysematous cholecystitis in diabetics, and in men who develop cholecystitis. Gallstones are seen in many but not all cases of emphysematous cholecystitis; there are many documented cases of acalculous emphysematous cholecystitis.

Management includes the prompt initiation of intravenous antibiotics that cover a broad spectrum of gram-negative organisms and definitive operative therapy. Of the antibiotic choices listed above, piperacillin/tazobactam would be the most appropriate choice, but other acceptable alternatives would include third-generation cephalosporins and quinolones (although anaerobic therapy should also be added). Amikacin is not an ideal initial line of therapy because of its potential nephrotoxicity and the need to monitor drug levels. In addition, it only covers gram-negative pathogens. Clindamycin would provide anaerobic coverage but would not cover the necessary spectrum of gram-negative organisms, including pseudomonas. Ampicillin/sulbactam, likewise would not provide coverage of pseudomonas. Cefazolin, with predominantly gram-positive coverage, would be inappropriate.

Reference:

Sawyer RG, Barkun JS, Smith R, et al. Intra-abdominal infection. In: Souba WW, Fink MP, Jurkovich GJ, Kaiser LR, Pearce WH, Pemberton JH, Soper NJ, eds. ACS Surgery: Principles and Practice. 4th ed. New York, NY: WebMD; 2004:1339-1340.

1B20

Key word: Preoperative Treatment of Increased INR from Warfarin

Author: Robert A. Meguid, MD, MPH

Editor: Frederick E. Eckhauser, MD, FACS

A 53-year-old man is brought into the emergency department after sustaining a gunshot wound to the left flank. You suspect a splenic injury with ongoing bleeding. The patient discloses that he is on warfarin, and his international normalized ratio (INR) is 3. What do you use to correct the coagulopathy en route to the operating room?

Temperature 38.3°C, WBC = 12, minimal pleural effusion, increased protein on bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), infiltrates not seen on chest radiograph

Temperature 38.3°C, WBC = 12, minimal pleural effusion, increased protein on bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), infiltrates not seen on chest radiograph Elevation of the child’s lower extremities with a pillow, followed by an attempt at manual reduction

Elevation of the child’s lower extremities with a pillow, followed by an attempt at manual reduction