TABLE 15.1 Differential Diagnosis of Benign Tumors of Adipose Tissue | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

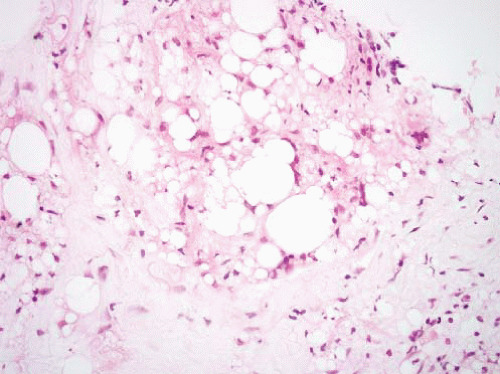

fat atrophy. It is often encountered as an incidental finding in specimens removed for any number of reasons and is mostly relevant because it can be confused with myxoid liposarcoma.

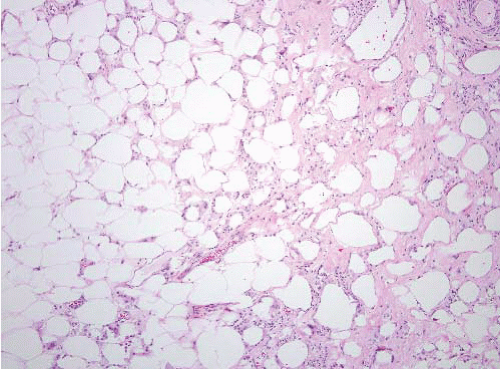

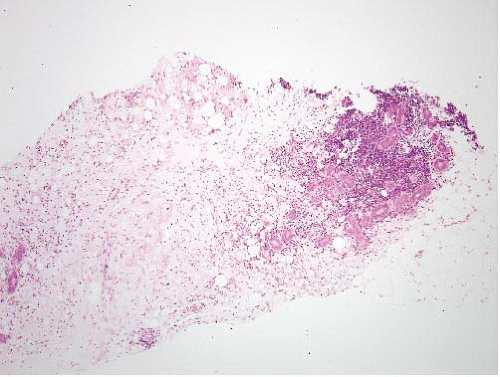

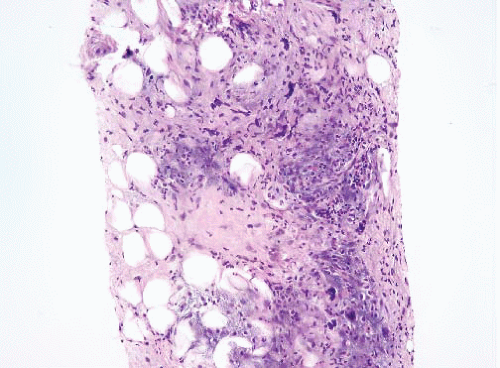

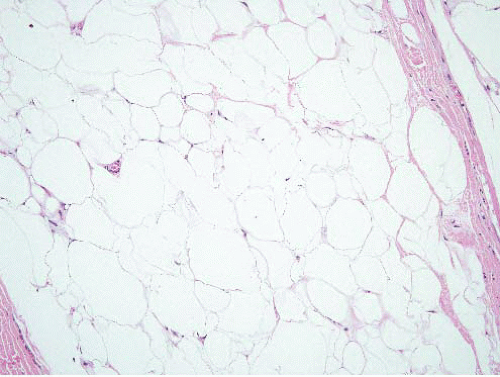

FIGURE 15.2 Lipoma with fat necrosis. This is how such foci appear at low magnification. Compare this image, original magnification 4×, to Figure 15.3, which is of a well-differentiated liposarcoma, also prepared at 4×. |

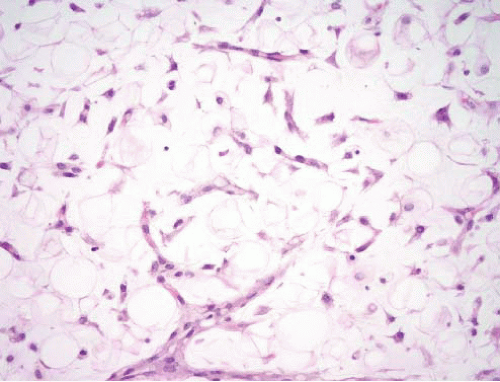

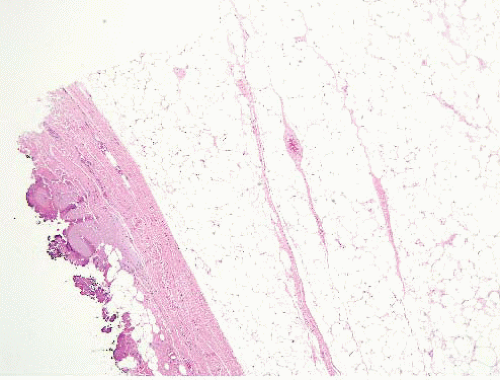

FIGURE 15.3 Well-differentiated liposarcoma. This image was taken at an original magnification of 4×, to compare with Figure 15.2. It shows scattered enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei that are readily apparent. |

crisply demarcated contents are reminiscent of lipoblasts. The silica gel does not consistently polarize, adding to the potential for a misdiagnosis.

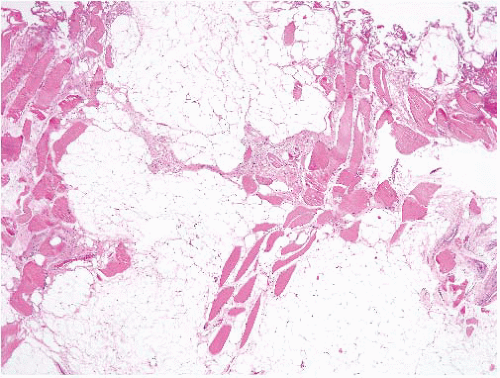

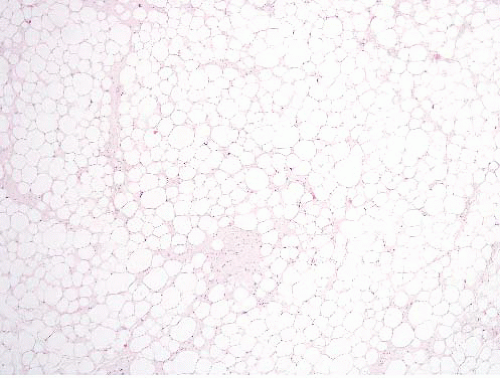

These microscopic subtypes do not have clinical significance. Superficial lipomas present as painless, soft, mobile masses that are generally small at the time of diagnosis (<5 cm). They are treated by simple excision. Recurrences are uncommon. Deep lipomas are generally larger at the time of diagnosis (>5 cm). They are typically painless but occasionally cause symptoms when they compress peripheral nerves. Deep-seated lipomas that arise within or between skeletal muscles are called intramuscular and intermuscular lipomas, respectively. Intramuscular lipomas affect patients in middle to late adult life. They occur in various locations including the trunk and upper and lower extremities.6 Intramuscular lipomas may be infiltrative or well circumscribed. This clinicopathologic distinction is important, as the infiltrative type has a tendency to locally recur following incomplete excision. Intermuscular lipoma, as the name implies, arises between muscles. It also affects adults and arises most often in the anterior abdominal wall. These are usually cured by local excision.

intramuscular lipoma, the mature adipocytes are arranged between skeletal myocytes (Fig. 15.9; e-Fig. 15.14). The most important pathologic differential diagnosis, especially for deep-seated lipomas, is low-grade liposarcoma. Well-differentiated liposarcoma generally has sclerotic bands containing cells with bizarre, hyperchromatic nuclei and occasional lipoblasts, whereas deep lipomas are composed only of mature adipocytes that do not demonstrate hyperchromasia or nuclear enlargement. A common pitfall, especially in evaluating thickly cut sections, in addition to that presented by fat necrosis (see Fig. 15.2, e-Fig. 15.3) is confusion of “lochkerne,” adipocytic cells with intranuclear lipid invaginations (Fig. 15.10), with the atypical nuclei found in well-differentiated liposarcomas or with lipoblasts (Fig. 15.11). All lipomas and lipoma variants can have foci of myxoid change, which can result in diagnostic problems. This is illustrated in electronic figures in Chapter 20 (e-Figs. 20.28, 20.33 to 20.41).

FIGURE 15.8 Lipoma. Compare the sizes of the lesional nuclei to those of nearby fibroblast and endothelial cell nuclei; they are similar. |

that these are, in fact, occult atypical lipomatous tumors lacking diagnostic histologic features.9 Since the usual issue confronting the pathologist is to exclude malignant neoplasms, however, often it is most useful to perform immunohistochemical stains for MDM2 or CDK4, as above (or fluorescence in situ hybridization for MDM2 amplification), to exclude well-differentiated liposarcoma. In most instances, however, special studies are not needed.

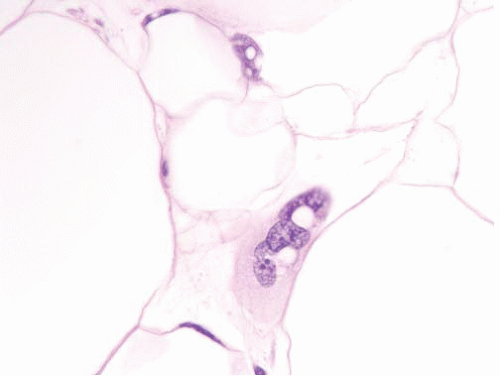

FIGURE 15.10 Lochkerne, an adipocyte nucleus with an intranuclear lipid invagination, oil immersion. The plane of section has captured the nucleus en face such that it is enlarged but not hyperchromatic. Compare it to the nucleus depicted in Figure 15.12, from a well-differentiated liposarcoma (taken at the same magnification and stained in the same laboratory), which is much more hyperchromatic. |

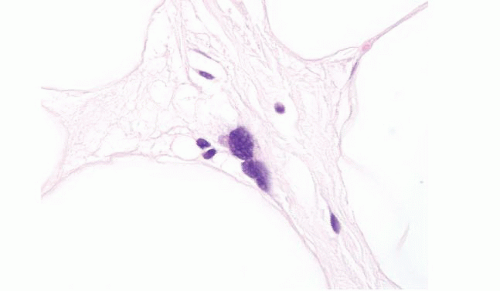

FIGURE 15.11 Well-differentiated liposarcoma, oil immersion. This image is intended to compare to Figure 15.11, which depicts a nucleus from a lipoma at the same magnification. |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree