Barrett’s

Malignant transformation of the esophageal epithelium

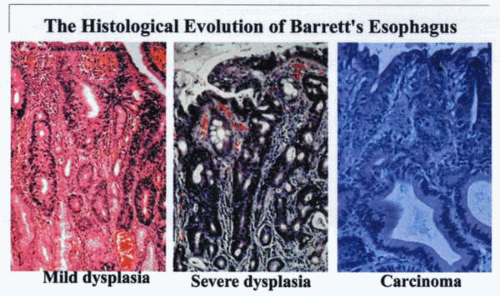

As with neoplasia elsewhere, the transformation from normal to a malignant mucosa occurs through a series of morphologic changes accompanied by specific molecular genetic events. The histologic changes in the squamous mucosa exposed to gastroesophageal reflux include an increase in the height of the rete pegs and an increase in the number of cycling epithelial cells. Whether the latter phenomenon is a direct effect of exposure of the gastric contents to the esophageal squamous epithelium or whether it is indirect is not known. Similarly, whether direct damage, including erosions, is necessarily the stimulus for transformation from squamous to columnar epithelium, as in Barrett’s esophagus, is not clear. Currently, it is thought that the development of a Barrett’s-type mucosa containing gastric, small intestinal, or colonic-type cells often together in the same metaplastic esophageal gland is due to an altered process of differentiation from the pluripotent epithelial stem cells. The presence of abundant growth factors in the esophageal gland system suggests that a process analogous to that described for the UACL system may be implicated in the local repair process. As in many other cancers, p53 mutations and aneuploidy are common in esophageal dysplasia and cancer, and alterations of other molecules, such as cyclins and rab proteins, have been described. The precise relevance of such diverse molecular events to the pathobiology of the system is at this stage unclear. Indeed, the sequence of genetic events occurring in esophageal cancer is not as well established as in the colon, although the potential use of these markers for screening purposes and possibly prognostic information is an area of considerable clinical and scientific interest.

Barrett’s esophagus

History

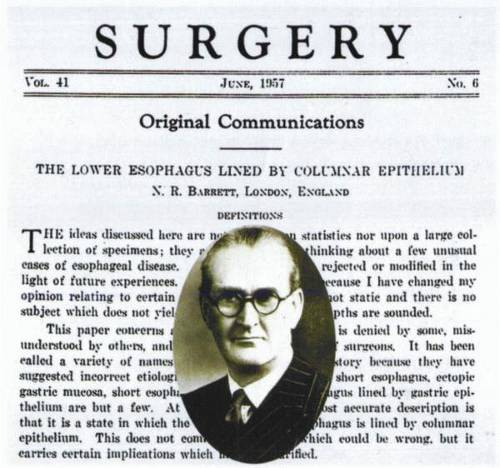

Norman Barrett, in 1950, published a report in the British Journal of Surgery in which he defined the esophagus as “that part of the foregut, distal to the cricopharyngeal sphincter, which is lined by squamous epithelium.” He

went on in this article to describe a number of patients who had ulcerations in a tubular, intrathoracic organ that appeared to be the esophagus except that its distal portion was lined extensively by a gastric type of columnar epithelium. Because the esophagus was by definition a squamous-lined structure, Barrett believed that the columnar-lined organ was a tubular segment of stomach generated by traction induced by a congenitally short (squamous-lined) esophagus and tethered within the chest. In this report, Barrett did not identify intestinal features (goblet cells) in the columnar lining of the tubular organ, nor did he raise the question of intestinal metaplasia. This issue was first noted in 1951 by Bosher and Taylor, who commented on the appearance of heterotopic gastric mucosa in the esophagus with ulceration and stricture formation. They noted that “the gastric mucosa was composed of glands which contained goblet cells but not parietal cells.”

went on in this article to describe a number of patients who had ulcerations in a tubular, intrathoracic organ that appeared to be the esophagus except that its distal portion was lined extensively by a gastric type of columnar epithelium. Because the esophagus was by definition a squamous-lined structure, Barrett believed that the columnar-lined organ was a tubular segment of stomach generated by traction induced by a congenitally short (squamous-lined) esophagus and tethered within the chest. In this report, Barrett did not identify intestinal features (goblet cells) in the columnar lining of the tubular organ, nor did he raise the question of intestinal metaplasia. This issue was first noted in 1951 by Bosher and Taylor, who commented on the appearance of heterotopic gastric mucosa in the esophagus with ulceration and stricture formation. They noted that “the gastric mucosa was composed of glands which contained goblet cells but not parietal cells.”

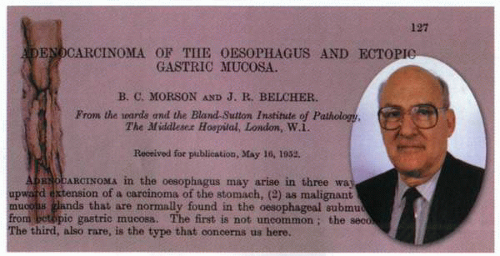

A year later, Basil Morson, together with Belcher, commented on the relationship of adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and ectopic gastric mucosa. They noted that in an individual with adenocarcinoma, the esophageal mucosa exhibited “atrophic changes with changes towards an intestinal type containing many goblet cells.” In 1953, Allison and Johnstone proposed that Barrett had misidentified the columnar-lined intrathoracic structure as stomach and that, in reality, it was the esophagus lined with gastric mucous membrane. They noted that, in contrast to the stomach, the structure lacked a peritoneal covering, often harbored islands of squamous epithelium, and possessed some mucosal glands and a muscularis propria characteristic of the esophagus. Thus, 7 years after his original report, Barrett reversed himself and concurred that the columnar-lined organ that he had previously believed to be the stomach was, in fact, the esophagus and suggested that the condition now be called “lower esophagus lined by columnar epithelium.” Despite this volteface, the condition to this time remains known as Barrett’s esophagus and continues to evoke as much confusion as when initially described.

In the first decade of its recognition, most believed that the esophageal columnar lining was congenital in origin but noted a common association with hiatal hernia and severe reflux esophagitis. It remained until 1959 for Moersch and his colleagues to propose that the columnar epithelium was not congenital in origin but acquired as a sequela of reflux esophagitis. Hayward, in 1961, commented on the vulnerability of the squamous epithelium at the site where it joined the gastric epithelium. He felt that it would be liable to digestion at this junctional zone and proposed “a buffer zone of junctional epithelium which does not secrete acid or pepsin but is resistant to them and has to be interposed.” For the subsequent 2 decades, the histology of the columnar-lined epithelium remained a controversial issue. Various investigators described an

esophagus lined by junctional epithelium, some noted the presence of acid and an acid-secreting fundic type of epithelium, and others described an intestinal type of epithelium with goblet cells. In 1976, Paull clarified the situation in patients with Barrett’s esophagus by obtaining biopsy specimens at specified levels throughout the esophagus using manometric guidance.

esophagus lined by junctional epithelium, some noted the presence of acid and an acid-secreting fundic type of epithelium, and others described an intestinal type of epithelium with goblet cells. In 1976, Paull clarified the situation in patients with Barrett’s esophagus by obtaining biopsy specimens at specified levels throughout the esophagus using manometric guidance.

Using this technique, the distal esophagus was noted to possess a combination of one to three types of columnar epithelia: (a) a junctional type of epithelium, (b) a gastric fundic type of epithelium, and (c) a distinctive type of intestinal metaplasia that was termed specialized columnar epithelium. The former two epithelial types were noted to be indistinguishable from the columnar epithelium normally identified in the stomach. However, the specialized intestinal metaplasia with its prominent goblet cells could readily be distinguished from normal mucosa. In addition, the three epithelial types were noted to occupy different zones in the esophagus, with a specialized intestinal metaplasia adjacent to squamous epithelium in the most proximal segment of the columnar lining. The junctional-type epithelium was noted to be present in the most distal esophageal segment, and the gastric fundictype epithelium was directly adjacent to the columnar mucosa of the stomach, which it joined.

Continued damage to the lower esophagus over a varying period results in transformation of the cell type and may culminate in neoplasia. |

By the 1970s, it was firmly established that the columnar-lined esophagus was often associated with severe GERD. There was controversy as to whether normal esophagus could be lined by columnar epithelium.

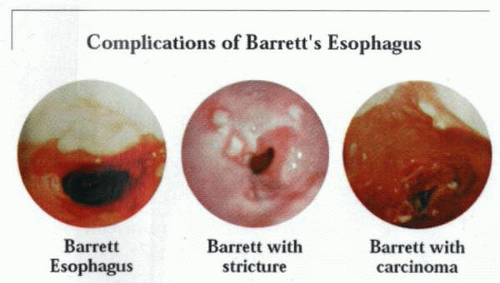

Because the association of large hiatal hernias with extensive esophageal inflammation often obscured the endoscopic landmarks of the junction between the esophagus and the stomach, false-positive diagnoses of Barrett’s esophagus abounded.

This became a source of considerable concern with the widespread recognition of the relationship between adenocarcinoma and Barrett’s esophagus. In the latter instances, the columnar epithelium surrounding the tumor invariably contained specialized intestinal metaplasia that often exhibited dysplasia. The recognition that specialized intestinal metaplasia was the epithelial type that predisposed to dysplasia and cancer development generated a major interest in the biology of this lesion and its early identification.

Current status

The last decade has led to disagreement as to the diagnosis and management of Barrett’s esophagus, particularly as it relates to the possible evolution of malignant disease. To a large extent, the issue has been fueled by the extraordinary

rise in incidence of adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction and the gastric cardia in particular.

rise in incidence of adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction and the gastric cardia in particular.

The histologic changes in the lining of the lower esophagus are associated with topographic alterations of considerable biologic and clinical importance. |

The critical questions that have arisen have not as yet been adequately resolved. Thus, the precise definition of Barrett’s esophagus by the identification of the extent of esophageal columnar lining has not been confirmed. Furthermore, problems in defining Barrett’s esophagus by the presence of intestinal metaplasia require certainty as regards biopsy sampling sites and histologic identification.

Finally, there exists a considerable degree of confusion with regard to the relationship between the extent of the esophageal columnar lining, specialized intestinal metaplasia, and GERD.

It is apparent, however, that the greater the length or extent of the esophageal columnar lining of the esophagus, the greater the frequency of the finding of intestinal metaplasia. Indeed, the frequency of specialized intestinal metaplasia at the squamocolumnar junction may be said to vary linearly with the extent of columnar epithelium lining the esophagus.

Given the degree of confusion that exists regarding the term Barrett’s esophagus, an alternative classification that does not rely on arbitrary and imprecise endoscopic measurements has been proposed by Spechler. Thus, when columnar epithelium is detected in the esophagus, regardless of its extent, the condition should be called columnar-lined esophagus, as originally proposed by Barrett. Once biopsy samples have been obtained from this esophageal columnar lining, the use of histologic criteria can then be used to classify the condition as either columnar-lined esophagus with specialized intestinal metaplasia or columnar-lined esophagus without specialized intestinal metaplasia.

This proposal provides considerable improvement in clarity for both physicians and pathologists with regard to the entity under consideration in a particular patient.

Although both conditions may be associated with GERD, the association is variable and appears to be related to the extent of the columnar lining. Thus, individuals with long segments of esophageal columnar lining often exhibit both severe GERD and specialized intestinal metaplasia. Signs and symptoms of GERD, however, may be absent in patients with short segments of columnar lining in the distal esophagus, even when biopsy specimens reveal specialized intestinal metaplasia.

Thus, endoscopic surveillance for adenocarcinoma may be recommended in individuals who have columnar-lined esophagus with intestinal metaplasia, irrespective of the extent, whereas columnar-lined esophagus without specialized intestinal metaplasia does not require endoscopic surveillance.

In the situation in which the distal esophagus appears normal and specialized intestinal metaplasia is identified at the squamocolumnar junction, which does not extend appreciably above the anatomic junction of the esophagus and the stomach, the condition should be called specialized intestinal metaplasia at the esophagogastric junction. It has not been established whether this condition is related to GERD, nor is it evident that the risk of cancer applies to patients with this condition.

Barrett’s esophagus had been identified primarily in patients with the signs and symptoms of GERD and in whom endoscopic examination revealed a long segment of columnar epithelium extending well up into the esophagus. Biopsy specimens taken from the columnar lining usually reveal an unusual form of intestinal metaplasia called specialized intestinal metaplasia, and the intestinal lining is invariably evident in the columnar epithelium surrounding Barrett’s adenocarcinomas. As a result of such observations, Barrett’s esophagus with specialized intestinal metaplasia became recognized as a major risk factor for adenocarcinoma at the gastroesophageal junction. The similar recognition that adenocarcinoma of the gastroesophageal junction was increasing at a dramatic rate in the United States and western Europe led to the development of a high level of interest in the pathology, early identification, and treatment of the condition. Of note is the observation that individuals who undergo esophagectomy for adenocarcinoma at the gastroesophageal junction often do not exhibit endoscopically apparent Barrett’s esophagus but more often have short inconspicuous segments of specialized intestinal metaplasia only evident at histologic examination of the specimen. This observation accords well with reports that in 18% of elective endoscopy patients with no evidence of Barrett’s esophagus (columnar-lined epithelium less than 3 cm of the distal esophagus), biopsies of the Z line (squamocolumnar junction) revealed specialized intestinal metaplasia. It is evident from this and other similar studies that short inconspicuous segments of specialized intestinal metaplasia can be frequently found at the Z line in predominantly Caucasian populations.

Clinical Relevance of Barrett’s Esophagus | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|