Learning Objectives

Learn the common autoimmune diseases involving primarily the connective tissue.

Understand the disorders associated with immune deficiencies and their underlying pathophysiology.

Learn the diagnostic tests required to establish a diagnosis for autoimmune disorders and for immunodeficiency disorders.

The immune system is a tightly regulated network that incorporates both innate and adaptive pathways. The genes regulating the innate system are coded in the germ line. The innate immune system is not antigen specific. The cells and soluble factors of the innate system have pattern recognition receptors (PRRs, such as toll-like receptors) to common motifs on pathogens and altered self-motifs. The motifs on pathogens are called pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs). Altered self-antigens include danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) as found in heat shock protein, and apoptosis-associated molecular patterns (AAMPs) as found in ds DNA, RNP, and histones. This response is rapid and there is no memory of the encounter.

The receptors on the T and B cells of the adaptive immune system are antigen or epitope specific and clonally variable, and their diversity is derived from gene recombination. The cells retain memory of the encounter and on subsequent engagement with that antigen, the cells exhibit more rapid and robust responses.

The following 2 groups of disorders are the focus of this chapter: the autoimmune diseases involving the connective tissue and the immunodeficiency diseases.

The immune network is tightly regulated by cells and cytokines, and a derangement in this immune homeostasis can result in immune response to self-antigens as in autoimmunity (failure of self-tolerance), or failure to recognize pathogens and eliminate them as occurs in immunodeficiency syndromes (failure of immunity). The following 2 groups of disorders are the focus of this chapter: the autoimmune diseases involving the connective tissue and the immunodeficiency diseases.

Diseases in which immune responses to self-antigens occur in the context of a genetic predisposition to disease expression are called autoimmune diseases. Some involve organ-specific pathologic autoimmunity such as Hashimoto thyroiditis and celiac disease, and these are discussed in Chapters 22 and 15, respectively. The autoimmune disorders discussed in this chapter are systemic diseases with predominant involvement of the connective tissue, manifesting clinical features including inflammation of the joints, skin, muscles, and other soft tissues (see Tables 3–1 and 3–2 and Figure 3–1).

| Disease | % ANA Positive | Titer | Common Patterns |

|---|---|---|---|

| Systemic lupus erythematosus—active | 95–98 | High | H > S > R |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus—remission | 90 | Moderate–high | H > S |

| Mixed connective tissue disease | 93 | High | S > N |

| Scleroderma/CREST | 85 | High | S > C > N |

| Sjogren syndrome | 48 | Moderate–high | S > H |

| Polymyositis/dermatomyositis | 61 | Low–moderate | S > N |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 41 | Low–moderate | S |

| Drug-induced lupus | 100 | Low–moderate | S |

| Pauciarticular juvenile chronic arthritis | 71 | Low–moderate | S |

| Disease | % ANA Positive | Titer | Common Patterns |

|---|---|---|---|

| Graves disease | 50 | Low–moderate | S |

| Hashimoto thyroiditis | 46 | Low–moderate | S |

| Autoimmune hepatitis | 63–91 | Low–moderate | S |

| Primary biliary cirrhosis | 10–40 | Low–moderate | S |

The immunodeficiency diseases are subdivided into the relatively rare primary and the more common secondary immunodeficiency diseases. Primary immunodeficiency diseases are a direct consequence of either structural or functional derangement in the immune network. Secondary immune deficiency is the manifestation of a primary infectious disease, such as HIV infection; a malignancy as seen in lymphoma and multiple myeloma; or exposure to a therapeutic regimen such as immunosuppression or radiation.

Systemic Autoimmune Diseases Involving the Connective Tissue

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a multisystem autoimmune disease, associated with the production of antibodies to a variety of nuclear and cytoplasmic antigens. The hallmark characteristic is the generation of antibodies to ds DNA. These antibodies complex to these self-antigens, and the ensuing immune complexes contribute to the inflammation in many organs, particularly the skin, joints, kidney, and, to a lesser extent, the cardiovascular and nervous systems, lung, and hemopoietic cells.

The disease is more common in women than in men and usually appears in early adulthood, although it is seen in children as well. It not only is more common in African Americans than in Caucasians but also has a more severe clinical phenotype with renal and vasculitic manifestations in African Americans.

The candidate genes associated with SLE include those coding for complement components C1q, C4A, C2, activating and inhibitory FcγR, interferon regulatory factor 5 (IRF5), TNF, MHC class II (DR2 and DR3), and programmed cell death PDCD1, among others.

Table 3–3 summarizes the laboratory evaluation of SLE and Table 3–4 lists the autoantibodies associated with SLE.

| Laboratory Tests | Results/Significance |

|---|---|

| Complete blood count and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) | Decrease in RBC, WBC, and platelets either singly or in combination suggests the presence of autoimmune cytopenias; serial CBC is useful to monitor bone marrow response to immunosuppressive therapy; ESR if elevated is a useful parameter to follow with therapy |

| Urinalysis and BUN/creatinine | Urinalysis is useful to evaluate proteinuria and any cellular sediments and casts; 24-hour protein excretion and BUN/creatinine are useful to monitor renal function |

| Liver function tests and lipid profile | For evaluation of possible autoimmune hepatitis; alterations in plasma lipids either due to disease or as a sequelae of therapy are to be appropriately managed to prevent cardiovascular complications |

| VDRL/RPR test for syphilis | False-positive VDRL test is noted in SLE; a positive VDRL in the absence of syphilis (negative RPR) is a diagnostic criterion for SLE |

| Antinuclear antibody | 95%-98% of patients with active SLE have a positive ANA |

| Complement assay | C3, C4, and factor B are useful to evaluate complement activation; CH50 to detect congenital complement deficiency especially in familial SLE; low complement values may reflect disease activity |

| Antigen Specificity | Prevalence (%) | Pattern on Hep-2 Cells | Clinical Associations |

|---|---|---|---|

| ds DNA | 40–60 | Homogeneous | Marker of active disease; titers fluctuate with disease activity; correlates best with renal disease |

| SS-A/Ro | 40 | Speckled, fine | Subacute cutaneous lupus (75%), neonatal lupus with heart block, complements deficiencies and photosensitivity |

| SS-B/La | 10–15 | Speckled, fine | Neonatal lupus |

| Sm | 20–30 | Speckled, coarse | Specific marker for SLE; may be associated with CNS disease; not useful in monitoring disease activity |

| RNP (U1 RNP) | 30–40 | Speckled, coarse | Generally coexists with Sm; RNP is a marker for MCTD |

| Histones | 50–95 | Homogeneous | 50%-70% in SLE and >95% in drug-induced SLE |

| Phospholipids (beta-2 glycoprotein I antibodies) | 30 | None specific | Associated with thrombocytopenia, later trimester abortions, and hypercoagulable states |

| Proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) | 3 | Finely granular nuclear staining in rapidly dividing cells | Not sensitive but specific (>95%); not seen in RA, other connective tissue disease; antibody rapidly diminished by steroids and immunosuppressive drugs; correlates with arthritis |

According to the American Rheumatologic Association criteria for diagnosis of SLE, the diagnosis of SLE is made if 4 or more of the following 11 criteria are present at any time during the course of the disease:

| Malar rash | Flat or raised fixed erythema over the malar eminences and sparing the nasolabial folds |

| Discoid rash | Erythematous raised patches with adherent keratotic scaling and follicular plugging; scarring may occur in older lesions |

| Photosensitivity | Skin rash resulting from reaction to light |

| Arthritis | Nonerosive arthritis involving 2 or more peripheral joints that are swollen or tender and evidence of effusion |

| Oral ulcers | Mostly painless ulcers in the oral cavity and pharynx |

| Serositis | Pleuritis with pleural rub or effusion; pericarditis documented by rub, EKG change, or pericardial effusion |

| Renal diseases | Persistent proteinuria greater than 0.5 g/day or 3+ on dipstick or presence on RBC, granular, tubular, or mixed cellular casts |

| Neurologic | Seizures or psychosis in the absence of metabolic or drug-induced causes |

| Hematologic | Any immune cytopenia—RBC, WBC, or platelets |

| Immunologic | Positive anti-ds DNA antibody, positive antiphospholipid antibody, positive anti-Sm antibody, and false-positive serologic test for syphilis |

| Antinuclear antibody | An abnormal ANA titer by immunofluorescence or an equivalent assay in the absence of drugs known to be associated with “drug-induced lupus” |

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a multisystem autoimmune disease, associated with the production of antibodies to a variety of nuclear and cytoplasmic antigens. The hallmark characteristic is the generation of antibodies to ds DNA.

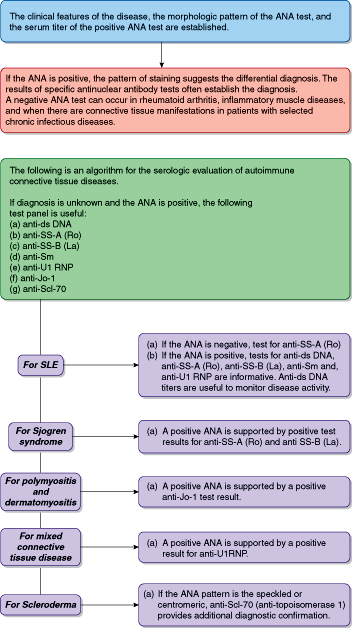

Tests utilized in the initial evaluation and subsequent monitoring of patients with SLE are shown in Tables 3–3 and 3–4 and Figure 3–1.

Sjogren syndrome (SS) is a systemic connective tissue disease, more common in women than in men. Pathologically, it is an autoimmune exocrinopathy involving the lacrimal glands, salivary glands, and less often the pancreas. The immune inflammation of these glands contributes to the sicca syndrome, with dry eyes (keratoconjunctivitis) and dry mouth (xerostomia) as characteristic clinical features. The disease can be primary or secondary. The primary syndrome is characterized by dry eyes, dry mouth, decreased production of tears as tested by the Schirmer test, and a lip biopsy that demonstrates inflammation of the minor salivary glands. Serologically, patients with primary Sjogren show a positive ANA, positive SS-A (Ro), positive SS-B (La), and positive rheumatoid factor (RF) in the absence of another connective tissue disease. A prospective study of 80 patients with primary SS followed for a median of 7.5 years reported the following frequencies of clinical manifestations: a) keratoconjunctivitis sicca and/or xerostomia occurred in all patients and were the only disease manifestations in 31%; b) extraglandular involvement occurred in 25%; and c) non-Hodgkin lymphoma developed in 2.5%. Secondary SS is clinically similar to the primary disorder, but it is additionally associated with clinical and serologic features of another connective tissue disease, such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA) or scleroderma.

The diagnostic features are revealed by tests that document the sicca features. The dry eyes are evaluated by the Schirmer test. This test is a measurement of tear flow over a 5-minute period. Filter paper is allowed to hang from the lateral inferior eyelid and the length of the paper that becomes wet is measured. This test is not reliable, as early in the disease there is excessive lacrimation giving a false-negative test. Demonstration of devitalized corneal epithelium due to keratoconjunctivitis is evaluated by rose Bengal or fluorescein stain. The most accurate test is the slit lamp examination of the cornea and conjunctiva. Tests for quantitating salivary secretion are not standardized and also are not specific to SS. Biopsy of the minor salivary gland in the lower lip demonstrating focal lymphocytic infiltration is a useful confirmatory test.

Systemic sclerosis is characterized by excessive and often widespread deposition of collagen in many organ systems of the body. Pathologically, the hallmark is the deposition of altered collagen in the extracellular matrix and a proliferative and occlusive small vessel vasculopathy.

Table 3–5 summarizes the laboratory tests useful in diagnosis of both primary and secondary SS.

| Findings in Sjogren Syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Diagnostic tests for dry eyes | |

| Schirmer test | <5 mm wet zone on filter paper in 5 minutes. |

| Rose Bengal dye test | Visualization of devitalized areas in cornea |

| Tear breakup time | Measuring breakup time and tear osmolality after installation of fluorescein; identifies those who respond to anti-inflammatory therapy |

| Diagnostic tests for dry mouth | |

| Salivary gland scintigraphy | Low uptake of radionuclide is specific for SS, but 33% of patients have a positive test; not a sensitive test |

| Lower lip biopsy | Presence of lymphoid infiltrate around salivary glands is consistent with disease |

| Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) | MRI is superior to ultrasonography and CT studies and is equivalent to sialography; correlates well with salivary gland biopsy |

| General laboratory tests | |

| Complete blood count including differential count | Anemia, neutropenia, lymphopenia, and thrombocytopenia may suggest immune destruction. Marked lymphocytosis may suggest clonal proliferation |

| Serum electrolytes and liver elevated function tests | Hypokalemia if associated with renal tubular acidosis, elevated alkaline phosphatase suggests primary biliary cirrhosis |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein | Markers for chronic and acute inflammation |

| Urinalysis | Proteinuria, casts imply renal involvement |

| Quantitative immunoglobulins (IgG, IgM, IgA) | Polyclonal increase is often noted |

| Serum and urine protein electrophoresis (SPEP and UPEP) and serum free light chains with altered kappa/lambda ratio | Transformation from polyclonal to monoclonal gammopathy implies evolution to a B-cell lymphoma. Presence of urine Bence-Jones protein confirms monoclonal transformation |

| Laboratory tests for autoimmunity | |

| Antinuclear antibody (ANA) titer | Commonest pattern is speckled; titer greater than 1:160; in 75% of patients |

| Antibodies to SS-A (Ro) | With ELISA >90% have a positive test |

| Antibodies to SS-B (La) | With ELISA >90% have a positive test |

| Rheumatoid factor | 70% have positive RF |

| Cryoglobulins, C3, and C4 | Presence of cryoglobulins and low C3 and C4 are found with multisystem disease |

| Anti-ds DNA antibody | In 25%-30% of patients with primary SS |

Systemic sclerosis is characterized by excessive and widespread deposition of collagen in many organ systems of the body. The hallmark of this pathologic process is the deposition of altered collagen in the extracellular matrix. The disorder is characterized pathologically by 3 features: 1) tissue fibrosis; 2) a proliferative and occlusive vasculopathy of the small blood vessels; and 3) a specific autoimmune response associated with distinctive autoantibody profile.

The immunologic basis is not well understood, but an aberration in TGF-beta-mediated deposition of collagen has been observed. Antibodies to platelet-derived growth factor receptors have been incriminated in the development of fibrosis. Both the triggering event and genetic predisposition are not well defined. Although the common organ involved is the skin, the gastrointestinal tract, kidney, lung, and muscles are also affected as the disease progresses. Renal ischemia leading to hypertension escalates the complications of this disease. Preponderance in females is common.

Clinically there are 4 major subtypes described:

Diffuse cutaneous scleroderma with widespread involvement of skin and visceral organs.

Limited cutaneous scleroderma, in which the disease is limited to the digital extremities and face. CREST syndrome is a variant of this entity. The name is derived from its features—calcinosis, Raynaud syndrome, esophageal dysmotility, sclerodactyly, and telangiectasia.

Localized scleroderma that affects primarily the skin of the forearms, the fingers, and later the systemic organs.

Overlap syndromes with features of RA or muscle involvement.

Ninety percent to 95% of all patients with scleroderma have a positive ANA test. The most common pattern is finely speckled, followed by centromeric and nucleolar patterns. The ANA activity is directed against DNA topoisomerase (also known as Scl-70). A definitive diagnosis is achieved when the characteristic clinical findings are accompanied by a positive ANA test, and often confirmed by an antibody directed to Scl-70 by ELISA.

Sjogren syndrome is characterized by immune-mediated destruction of exocrine glands, particularly the salivary and lacrimal glands, with secondary development of keratoconjunctivitis and xerostomia. A positive ANA along with antibodies to SS-A (Ro) and/or SS-B (La) is a serologic feature. Transition from a polyclonal rheumatoid factor (RF) positive to a RF-negative oligoclonal or monoclonal process suggests a malignant lymphomatous transformation.

Tables 3–6.1 and 3–6.2 summarize the laboratory evaluation for systemic sclerosis/scleroderma.

| Laboratory Test | Scleroderma | CREST Syndrome |

|---|---|---|

| Pattern of ANA (Hep-2) | Speckled | Centromeric |

| Commonly found autoantibody | Anti-Scl-70 (greater in diffuse disease than in localized disease) | Mostly anticentromeric with a distinctive pattern on Hep-2 cells |

| Autoantigens | Description of Phenotype |

|---|---|

| Scl-70/Topo 1 or topoisomerase 1 | 25%-40% of patients with diffuse scleroderma; associated with severe lung disease |

| ACA or centromere | 55%-96% of patients with CREST syndrome. CENP-B (100%) and CENP-C (50%) are the targets. Seen in Raynaud phenomenon and in about 10% of patients with primary biliary cirrhosis |

| RNA polymerase I, II, and III | 4%-20% of patients with diffuse skin disease and renal involvement and less lung and muscle involvement |

| Fibrillarin (U3 snRNP) | 8%-10% of patients with cardiopulmonary and muscle involvement. Higher prevalence in blacks and Native Americans |

| PM-Scl | A nucleolar complex seen in association with inflammatory muscle disease in scleroderma |

| Th/To RNP (endoribonuclease) | 10% of patients with limited scleroderma and associated with pulmonary hypertension and fibrosis |

| U1 snRNP (U1 RNP and polypeptides) | Associated with overlap syndrome and mixed connective tissue disease |

| B-23 (nucleophosmin) | A nucleolar phosphoprotein associated with pulmonary hypertension and overlap syndrome |

Inflammation of the muscle leading to injury and weakness is the basis of the 3 most common but distinct diseases in this category. They are dermatomyositis (DM), polymyositis (PM), and inclusion body myositis. These diseases are more common in women, and their etiology remains unknown, although immune mechanisms have been incriminated. DM may occur as a specific entity or be associated with scleroderma or mixed connective tissue disease. Rarely, it is a manifestation of a malignancy. Skin manifestations such as a heliotrope rash, the shawl sign, and Gottron papules are common in DM. Like DM, PM may also be associated with another connective tissue disease. In addition, it may be associated with viral, parasitic, or bacterial infections. DM is characterized by immune complex deposition in the vessels and is considered to be in part a complement-mediated vasculopathy. In contrast, PM appears to reflect direct T-cell-mediated muscle injury. Inclusion body myositis is a disease of older individuals and is not associated with malignancy. It is occasionally associated with another connective tissue disease.

Inflammation of the muscle leading to injury and weakness is the basis of the 3 most common but distinct diseases in this category. They are dermatomyositis (DM), polymyositis (PM), and inclusion body myositis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree