Pharmacotherapy

Both research and clinical experience provide strong evidence that many antidepressants are effective therapies for PD, particularly for patients with comorbid depression.

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors. Because of their more acceptable tolerability profile, the SSRIs are usually the antidepressants of first choice for PD (

21,

27). Studies consistently indicate that SSRIs, such as paroxetine, sertraline, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine and citalopram, all possess acute antipanic efficacy and are better tolerated than TCAs or MAOIs (

Tables 13-1 and

13-2;

28,

29,

30,

31,

32 and

33). The existing evidence for their long-term effectiveness in panic treatment is limited and more data are needed (

34,

35,

36 and

37). Some evidence, however, indicates that long-term therapy successfully maintains efficacy and may even produce continued improvement

(38). This is an important asset for any pharmacotherapy because PD is a chronic illness subject to relapse

(39).

Both the immediate-release (IR) and controlled-release (CR) formulations of paroxetine are approved for the treatment of PD with or without agoraphobia. Oral doses of 10 to 60 mg/day significantly reduce the frequency of panic attacks, but the lag time for onset of efficacy may be longer than when paroxetine is used as an antidepressant

(40). In addition, a pooled analysis of three 10-week, placebo-controlled trials found that the CR formulation of paroxetine was superior to placebo and produced low rates of treatment-emergent anxiety and dropouts due to adverse effects

(41).

Several short- and long-term studies also demonstrate that

sertraline in doses ranging from 50 to 175 mg/day is an effective treatment for PD (

42,

43). For example, one 10-week controlled trial involving 176 nondepressed outpatients with PD demonstrated this agent’s superiority to placebo in decreasing panic frequency

(44). In another report, data were pooled from four placebo-controlled trials of sertraline involving 664 patients at risk for poor outcome

(45). The results again supported this agent’s effectiveness in a chronic, recurrent form of PD.

Controlled trials demonstrate that

fluoxetine (20-40 mg/day) is also effective for PD in both acute and continuation designs (

46,

47 and

48). Further, because of its longer half-life, fluoxetine at doses ranging from 10 to 60 mg administered

once weekly is also an effective maintenance treatment for patients with PD who successfully respond to

daily fluoxetine

(49).

Given the available evidence for efficacy with all SSRIs, it is helpful to clarify if there are differences within this class. In this context, one double-blind, controlled trial

compared sertraline to paroxetine and found them equal in terms of efficacy, but sertraline was better tolerated

(50).

Adverse Effects. In general, SSRIs offer the benefits of easier dosing and no safety or dependence problems in contrast to TCAs and BZDs, respectively

(51). SSRIs, however, can cause an initial jitteriness similar to that seen with imipramine therapy for PD, and this symptom may be more common with SSRIs than other currently available non-TCA antidepressants. Just as low initial imipramine doses can prevent jitteriness, initiating SSRI therapies with one-fourth to one-half the usual starting antidepressant dose, followed by gradual increments, may avoid this reaction. This syndrome is also blocked by add-on, lowdose, as-needed BZD therapy (e.g., alprazolam or lorazepam).

Selective Serotonin/Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors. In earlier studies, venlafaxine XR consistently demonstrated efficacy for PD in several placebo-controlled, short- and long-term trials (

52,

53,

54 and

55). Most recently, however, a large (

n = 343), 10-week, multicenter, controlled trial using flexible doses (75-225 mg/day) demonstrated only a trend favoring active drug over placebo on the primary outcome measure (i.e., percent of panic-free patients)

(56). Mean change scores on the Panic Disorder Severity Scale (PDSS) and CGI-I, however, were statistically superior for venlafaxine XR over placebo.

A preliminary, 8-week prospective, open-label study in 15 patients with PD also found flexibly dosed

duloxetine (60-120 mg/day) effective

(57).

Tricyclic Antidepressants. In 1962, Klein and Fink

(58) reported that imipramine blocked panic attacks but had only a minor effect on phobic avoidance or anticipatory anxiety. This clinical observation was validated by several double-blind studies of TCAs that affirmed their antipanic efficacy. Although many agents in this class are effective, they differ in safety and tolerability from each other, as well as from newer generation antidepressants. In this context, clinicians must balance the known advantages and disadvantages of a drug, with the specific needs in a given patient.

Studies

comparing TCAs with placebo for the treatment of PD are summarized in

Table 13-3. All TCAs were consistently superior to placebo, although no significant differences in efficacy were noted among them. The results of studies

comparing TCAs with alprazolam are summarized in

Table 13-4 and also indicate comparable efficacy.

Imipramine is the first and most widely studied TCA for the treatment of PD, with excellent data to show that it is an effective antipanic agent (

59,

60 and

61). Doses of 150 to 250 mg/day as the sole or primary treatment produce a marked response rate (∽75%), making it the standard TCA pharmacotherapy for PD. Other TCAs reported to produce therapeutic benefit include (

62,

63)

Desipramine

Nortriptyline

Amitriptyline

Doxepin

Of note, while most studies comparing imipramine and alprazolam indicate that both drugs produce a comparable reduction of symptoms, the onset of action is considerably slower with this TCA (i.e., 2 to 12 weeks;

64,

65 and

66). In this context, the question of combining a

TCA with a BZD has not been formally studied. Nevertheless, to help

patients achieve the rapid results associated with BZD treatment, while avoiding the possibility of dependence and severe rebound that may occur on discontinuation, some recommend initiating treatment with low doses of a BZD and imipramine. The BZD is then gradually tapered and withdrawn when imipramine reaches therapeutic levels

(67). Thus, this short-term combination strategy can be helpful until the full impact of the antidepressant is realized and initial adverse effects subside

(68).

Data on recurrence of PD after TCA discontinuation from existing controlled and open trials note that patients often relapse after drug cessation. For example, Sheehan and Paji

(69) found that most of their PD patients had a recurrence when medication was stopped. Subsequent studies confirmed that therapeutic gains are lost in many instances when treatment is stopped after short-term medication or cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT)

(70). Relapse rates range from less than 33% to more than 90% (

59,

63,

71,

72,

73,

74,

75 and

76). An evaluation of long-term outcome of PD at a mean of 5.3 years following a controlled trial, however, found that complete recovery can occur even after many years of severe illness in a substantial proportion of patients who receive both antidepressants and behavioral counseling in the acute stage of treatment

(77).

In addition to producing anticholinergic effects and hypotension, TCAs may actually worsen the patient’s condition early in treatment by increasing anxiety, jitteriness, and dysphoria (63). Clomipramine may cause more jitteriness than other psychopharmacological treatments for PD. Very early in the clinical evaluation of imipramine, approximately 25% of patients initially reacted with feelings of restlessness, autonomic symptoms (sweating and flushing), and increased anxiety and apprehension. These psychological and physical symptoms generate unwanted subjective distress that prompted some patients to discontinue imipramine. Ultimately, these symptoms were found to be dose dependent and could be averted by starting with a low dose (e.g., 10 to 25 mg of imipramine), followed by gradual increments of 10 mg.

Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors. The MAOIs available in the United States (e.g., phenelzine and tranylcypromine) are effective antipanic and antiphobic agents. Results of trials

comparing MAOIs to placebo are summarized in

Table 13-5 and indicate a significantly greater benefit for these agents over placebo. Of these,

phenelzine is the most extensively studied and was effective in both open and controlled designs (

78,

79). Although clinical experience also indicates

tranylcypromine is an effective antipanic agent, there are no controlled trials confirming this observation. As with the other nonselective MAOIs, however, they also carry the risk of hypertensive and hyperpyrexic reactions (see

Chapter 7).

Selegiline TS, a type B MAOI, has a low propensity to cause hypertensive and hyperpyrexic reactions, but there is scant information on its use for PD.

Moclobemide, a selective and reversible inhibitor of monoamine oxidase A (RIMA), was not effective in one controlled trial

(80).

The onset of action of MAOIs is similar to that of other antidepressants. Although adverse effects tend to be less troublesome than with TCAs, dietary restrictions limit their usefulness in some patients. Unfortunately, the relapse rate appears comparable to BZDs and TCAs

(81). For example, in a follow-up of 246 patients, Kelly et al.

(82) found that 50% of those who discontinued their MAOI relapsed within 1 year.

Benzodiazepines. Early controlled studies with

alprazolam clearly demonstrated its antipanic properties. To achieve this benefit, this agent is often given in higher doses (4 to 10 mg/day). As noted earlier, alprazolam usually produces its therapeutic effect during the first week, whereas antidepressants may take several weeks. In addition, there is evidence that

clonazepam, diazepam, lorazepam, bromazepam, or

clobazam benefit patients with PD

(83).

While rapid onset of action and a favorable adverse effect profile are advantages that BZDs have over other antipanic drug therapies, not all

patients respond. Also, BZDs lack therapeutic efficacy for major depression, a common complication of PD. Furthermore, abrupt discontinuation of BZDs can produce withdrawal symptoms (see

Chapter 12). Nevertheless, familiarity with the assets and liabilities of BZDs enhances the art of antipanic pharmacotherapy (see

Table 13-6)

(21).

Alprazolam. Short-Term Efficacy. Although at least one study found no difference between alprazolam and placebo, several other short-term trials reported that this BZD reduces the frequency and intensity of panic attacks (

64,

81,

84,

85,

86,

87,

88 and

89;

Table 13-7). In phase I of the Cross-National Collaborative Panic Study, including approximately 500 patients at eight sites, alprazolam was superior to placebo at the end of week 1, improving spontaneous and situational panic attacks, anxiety, and secondary disability

(87). At week 4, 50% of alprazolam subjects and 28% of placebo subjects were free of panic attacks. At week 8, however, 50% of those on placebo were also free of panic attacks, compared with 59% of those receiving alprazolam. These data reflect group efficacy and not individual responses over time. Furthermore, there was considerable variability and, at times, instability of response in individual patients. Explanations offered for the high rate of placebo response in this and other studies include

The possible surreptitious use of antianxiety and antidepressant medication

Consistently normal dexamethasone suppression tests

Lower anxiety ratings at the start of treatment

Behavioral benefits derived from inclusion in the study (

90,

91 and

92)

Alprazolam was also compared with imipramine and placebo in a sample of 1,168 randomly assigned subjects in the Cross-National Collaborative Panic Study, Phase II

(93). This study was conducted at 12 centers and assessed clinical change over 8 weeks of double-blind treatment. Improvement occurred with alprazolam by weeks 1 and 2 and with imipramine by week 4. By the end of week 8, the effects of the two active drugs were similar, and both were superior to placebo on most outcome measures.

Long-Term Efficacy. The question of whether there is long-term benefit with alprazolam is less clear. Although improvement appears to be sustained in many patients as long as the medication is continued, some researchers report high rates of relapse within 14 months after drug discontinuation (

94,

95 and

96).

Nagy et al.

(97) conducted a 2.5-year followup study of 60 subjects with PD or agoraphobia with panic attacks who completed a 4-month combined drug and behavioral group treatment program and were discharged on alprazolam.

These authors found that short-term improvement was maintained during alprazolam maintenance, indicating that tolerance did not develop. Furthermore, many who decreased or discontinued the drug also sustained improvement. The ability to discontinue alprazolam was associated with lower initial frequency of panic attacks. Those patients receiving nonpharmacological therapy in the follow-up period tended to have greater symptom severity. Finally, current or past depression was related to greater illness severity, frequent episodes of depression after treatment, and lack of depression prevention by low-dose alprazolam plus behavioral therapy. Because of the naturalistic design and the use of both pharmacological and nonpharmacological interventions, the investigators cautioned that their results did not differentiate among the relative contributions of alprazolam, behavioral therapy, or their combination.

Dose. Because of its relatively short duration of effect (2 to 6 hours), alprazolam IR must be given in divided doses, as frequently as four to five times daily. The extended-release formulation, however, may be given less frequently and reduces the risk of interdose breakthrough symptoms

(98). In addition, Richels notes that the reduction in sudden plasma levels associated with this formulation may reduce abuse liability, sedation and cognitive and psychomotor impairment. Long-term treatment with this formulation, however, still carries a similar risk for dependence and withdrawal symptoms. In the treatment of PD, effective doses range from 2 to 10 mg/day, which are considerably higher than those recommended for generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). One acute fixed-dose study found that approximately 60% of subjects respond to 2 mg and 75% respond to 6 mg. In another study, 6 mg was also more effective than 2 mg (

65,

99).

Some evidence indicates that patients maintained on alprazolam may benefit from lower doses than those used initially. As noted earlier, Nagy et al.

(97) found that many subjects sustained their improvement with lower doses, and others report similar findings (

94,

100). By contrast, Rashid et al.

(101) found the need to increase the alprazolam dose over time.

Adverse Effects. Sedation, ataxia, said fatigue are the most common adverse effects reported with acute use of alprazolam in PD

(101). Although tolerance to the sedative effect may develop within a few days of treatment initiation, this adaptation may be only partial. At weeks 4 and 8 in the Cross-National Collaborative Study, many subjects still showed signs of sedation (48% and 39%, respectively), ataxia (25% and 16%, respectively), and fatigue (19% and 16%, respectively; 87).

In an open study of outpatients who took alprazolam for a mean of 13.3 months, Rashid et al.

(101) reported the occurrence of the following symptoms:

Bone or joint stiffness or lancinating pain

Excessive lacrimation without accompanying affect

Tightness in the intercostal muscles

Labored respirations or air hunger

Frequent changes in accommodation; visual clouding

Brief bursts of profuse sweating unrelated to exertion

Rapidly alternating mood swings

Some symptoms were withdrawal-like, occurring within a 4-hour time frame of any given dose. Other interdose symptoms such as irritability, increased anxiety, and panic are reported with alprazolam(102). The use of alprazolam in PD patients is also associated with

The emergence of

depressive symptoms, a phenomenon also reported with clonazepam and lorazepam (

96,

97,

103,

104 and

105)

Aggressive behavior and assaultiveness in patients with and without a history of major depression (

102,

106)

Possible increased incidence of

behavioral dyscontrol (107)

Emergence of behavioral dyscontrol is reported with a variety of BZDs and appears to be idiosyncratic. Researchers studied the question of whether there is an increased incidence with alprazolam. Rosenbaum et al.

(108) described extreme anger or hostility in 8 of 80 private practice patients (10%), one of whom had a history of aggressive behavior. Gardner and Cowdry

(109) reported that 7 of 12 (58%) patients with borderline personality disorder and a history of dyscontrol who were given alprazolam (1 to 6 mg/day) had serious recurrent episodes of dyscontrol. Finally, an FDA assessment of 329 drugs indicated that alprazolam ranked second (behind triazolam) for hostility reactions

(110).

Discontinuation Effects. As noted in Chapter 12, alprazolam requires an extended and very gradual taper, even when given for only a few weeks.Despite very slow dose reduction, however, a substantial number of patients may experience worsening of symptoms, including severe rebound panic and increased anxiety (

94,

96,

111,

112,

113 and

114). Two studies compared discontinuation effects in PD patients given either alprazolam or diazepam. Burrows et al.

(115) reported severe difficulties in 20% to 30% of patients discontinuing either drug, with those on diazepam having slightly more difficulty than those on alprazolam. Roy-Byrne et al.

(112) found greater increases in anxiety 1 week after abrupt discontinuation of medication in patients taking alprazolam compared with those taking diazepam. Although there were no significant differences in frequency of panic attacks during drug taper, at discontinuation the frequency of increased panic attacks was 50% higher in the alprazolam than in the diazepam group and three times greater in the diazepam versus the placebo group.

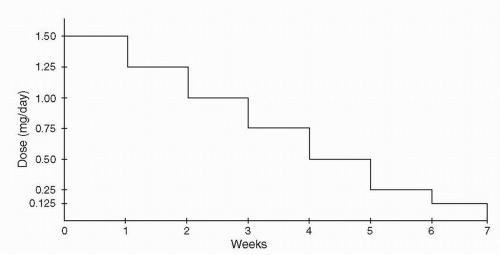

Other reported symptoms are listed in

Table 13-8. In some patients, symptoms may not occur in the initial phases of taper but appear when the dose reaches lower levels (

111,

112,

115). Withdrawal symptoms are reported to last as long as 4 weeks, although they may subside within 1 to 2 weeks (

96,

111). Abrupt taper or sudden discontinuation increases the risk of delirium and seizures (

116,

117 and

118). A guide to properly tapering alprazolam is provided in

Figure 13-1 (

119,

120). Further, one report found that CBT during alprazolam taper reduced related complications

(121).

Clonazepam. Short-Term Efficacy. Since its approval by the FDA in the mid-1990s, clinicians have successfully treated PD with agoraphobia using clonazepam

(122).

Several earlier, open trials reported significant improvement or remission of panic attacks in patients given clonazepam (

123,

124,

125,

126,

127,

128 and

129). A subsequent, double-blind, placebo-controlled study comparing the efficacy of alprazolam, clonazepam, and placebo found both drugs superior to placebo and comparable with each other

(130). Because favorable response to clonazepam usually occurs early in treatment, lack of initial improvement may predict treatment failure (

104,

124,

131). Further, interdose and morning rebound anxiety are usually not reported.

Long-Term Efficacy. One study found clonazepam effective for long-term use to manage PD or agoraphobia with panic attacks without development of tolerance as manifested by dose escalation or worsening of clinical status

(132).

In a 1-year follow-up study of clonazepam for PD or agoraphobia with panic attacks, Pollack et al.

(104) reported that 18 of 20 subjects (90%), many of whom had failed to respond to or tolerate other BZDs or antidepressants, maintained a good response. One subject was in complete remission at 44 weeks and remained well even off medication at 56 weeks. Tolerance to therapeutic efficacy did not appear to develop, although 40% required a dose increase (from 0.25 to 4.5 mg) to maintain initial improvement. Of note, 10 patients (50%) discontinued clonazepam at follow-up because of adverse effects, inadequate response, or preference for a previously used treatment.

Dose. Effective daily doses of clonazepam range from 0.25 to 9 mg. Daily doses of 1 to 3 mg offer

the best balance of therapeutic benefit and tolerability

(133). A review of open trials disclosed that most patients were maintained on 2 to 3 mg/day

(131). In the comparison between alprazolam and clonazepam, average therapeutic doses were 5.2 and 2.4 mg/day, respectively

(130). Because of its long half-life, clonazepam is usually given twice daily, in the morning and at bedtime. Initial lower doses in the morning allow for the development of tolerance to this agent’s sedative effect.

Switching from Alprazolam. Studies comparing clonazepam and alprazolam show that panic symptoms are equally controlled with both agents. In an open trial, Herman et al.

(134) recruited 48 PD patients successfully treated with alprazolam but distressed by interdose or morning rebound. Using a standard protocol, 41 subjects completed a transition to clonazepam treatment and 39 continued on this drug for a mean duration of 40 weeks at an average dose of 1.5 mg/day (range, 0.125 to 3 mg/day). Two subjects reported mild sedation but did not discontinue the medication. Although 2 others rated clonazepam as worse than alprazolam and switched back successfully to the latter, 34 rated clonazepam as better and 5 considered it the same as alprazolam.

Adverse Effects. Sedation is the most prominent initial effect of clonazepam, usually subsiding in 2 to 3 days, but it may persist in some patients. Other reported adverse effects include

Ataxia

Irritability

Nausea

Dysthymia

In their long-term follow-up study, Pollack et al.

(104) found that five patients had stopped clonazepam because of adverse effects (dysthymia, one; irritability, two; nausea and sedation, two) and that four patients required dose reductions because of adverse effects (predominantly sedation).

Like alprazolam, clonazepam may cause treatment-emergent

depression in some patients. Pollack et al.

(104) also reported that only 10% of their subjects who remained on clonazepam had a history of depression, although 47% lost to follow-up and 30% who eventually required alternate treatment had a history of dysthymia or depression. Of 31 subjects without a prior history of affective illness, depression developed in three on low daily dosages (0.75, 1.5, and 2 mg), one was switched to alprazolam, and the others responded to the addition of desipramine or imipramine. These investigators recommend that PD patients with chronic or concurrent depression should not receive clonazepam alone and that those in whom depression develops during therapy should have their dose lowered or an adjunctive antidepressant added.

Some evidence indicates that clonazepam may induce depression more often than alprazolam. In a review of 177 patients given clonazepam and a matched number given alprazolam, Cohen and Rosenbaum

(135) reported that depression developed in 5.5% of the

clonazepam patients compared with only 0.7% of those on alprazolam.

An earlier review found a high incidence of aggressive dyscontrol in neurological patients given clonazepam, most of whom were children

(136). This observation led to speculation that clonazepam may be associated with an increased incidence of aggressivity in psychiatric patients. In this context, there are reports of irritability in 2 of 50 panic patients and threatening or assaultive behavior in 4 of 13 schizophrenic patients on clonazepam (

104,

137). Other investigators, however, have not reported such adverse effects in patients with PD (

123,

126).

Discontinuation Effects. There is speculation that clonazepam’s longer duration of action may provide better protection against withdrawal symptoms and the rapid re-emergence of panic symptoms. Limited data are available on specific discontinuation effects associated with this treatment for PD, although mild rebound anxiety is observed

(126). A number of patients with a variety of psychiatric disorders were successfully switched from high daily doses of alprazolam to clonazepam (

138,

139). Subsequent gradual discontinuation of the latter produced no major withdrawal phenomena, although two patients experienced mild reemergence of panic symptoms that subsided with small dose increases. These symptoms did not recur during further dose tapering and discontinuation. Like all other BZDs, clonazepam should be reduced gradually because abrupt cessation may lead to withdrawal symptoms ranging from mild to severe (

140,

141).

In summary, discontinuation during and after slow tapering is usually well tolerated, resulting in a benign withdrawal course

(142). If discontinuation is appropriate or necessary, careful evaluation of withdrawal symptoms versus reemergence of the disorder itself is required (see also

Chapter 12). Discontinuation is probably easier with longer-acting, high-potency BZDs

(143). Withdrawal from higher doses, particularly rapid withdrawal, however, is associated with more severe symptoms

(144).

Other Benzodiazepines. There is some evidence that higher than usual doses of lower potency BZDs may be effective in treating PD (

83,

88,

105,

145,

146,

147 and

148). For example, studies comparing alprazolam with

lorazepam or

diazepam indicate approximately equal efficacy (

67,

88,

105,

148). In addition, there is evidence that higher than usual doses of

bromazepam or

clobazam are needed to block panic attacks.

Conclusion. Many patients require long-term, indefinite BZD therapy for their PD. Fortunately, most naturalistic follow-up studies indicate an absence of tolerance to the antipanic-antiphobic effects of these drugs. Indeed, many patients appear to derive efficacy at lower maintenance doses of BZDs

(149).

Anticonvulsants. A small database supports the use of anticonvulsants for the treatment of patients with PD.

Valproate. Studies with VPA included those with comorbid alcohol abuse and treatment-refractory PD (

150,

151,

152 and

153). At least a 50% reduction in panic attacks and at least a 40% complete remission were noted in these trials. In two placebocontrolled trials, there was a trend favoring VPA over placebo in reducing the number of spontaneous panic attacks and the duration of those attacks

(154). The dosage of VPA in these studies was comparable to that recommended for treatment of bipolar disorder

(155). VPA was also useful in the treatment of PD patients with concomitant mood instability who did not respond to conventional therapy

(156). Given the potential effect of this agent on the 7-aminobutyric acid (GABA) neurotransmitter system, its use alone or in combination with other GABAergic agents (e.g., clonazepam) may help treatment-resistant PD

(157). Larger, controlled investigations would clarify the role of this drug for treatment of PD.

Gabapentin. Preliminary evidence also supports the efficacy of gabapentin in the treatment of more severe PD

(158).

Second-Generation Antipsychotics

Risperidone. A randomized, rater-blinded study compared low-dose risperidone to paroxetine in 56 patients with PD

(159). Results were quite similar between the two treatments with risperidone having a more rapid onset of effect.

Olanzapine. A report of two patients with treatment-resistant PD indicated that olanzapine added to ongoing treatment with clonazepam

(2 mg/day), ketazolam (30 mg/day), and venlafaxine (150 mg/day) was beneficial

(160). The first patient was started on 7.5 nig at bedtime, and 2 weeks later he was much calmer and sleeping well. Olanzapine was increased to 12.5 mg/day and venlafaxine was replaced with nefazodone up to 60 mg/day. Over the next few weeks, he improved progressively, and clonazepam and ketazolam were discontinued. After 4 months, he was free from panic attacks and left his home alone. The second patient had 10 mg of olanzapine daily added to ongoing treatment with 75 mg/day of ami trip tyline and 10 mg/day of diazepam. After 2.5 months, she was still on olanzapine and had started going out on her own.

Given the concerns about neuromotor, weight, and metabolic complications, however, the use of antipsychotics must be limited to those patients whose symptoms warrant these risks.