Arthritis: Osteoarthritis, Gout, & Rheumatoid Arthritis: Introduction

Arthritis is a complaint and a disease afflicting many patients and accounting for upwards of 10% of appointments to a generalist practice. Arthritis is multifaceted and can be categorized in several different fashions. For simplicity, this chapter focuses on conditions affecting the anatomic joint composed of cartilage, synovium, and bone. Other discussions would include localized disorders of the periarticular region (eg, tendonitis and bursitis) and systemic disorders that have arthritic manifestations (eg, vasculitides, polymyalgia rheumatica, and fibromyalgia). The chapter discusses three prototypical types of arthritis: osteoarthritis, as an example of a cartilage disorder; gout, as an example of both a crystal-induced arthritis and an acute arthritis; and rheumatoid arthritis, as an example of an immune-mediated, systemic disease and a chronic deforming arthritis.

Osteoarthritis

- Degenerative changes in the knee, hip, thumb, ankle, foot, or spine.

- Pain with movement that improves with rest.

- Synovitis.

- Sclerosis, thickening, spurs formation, warmth, and effusion in the joints.

Arthritis is among the oldest identified conditions in humans. Anthropologists examining skeletal remains from antiquity deduce levels of physical activity and work by searching for the presence of osteoarthritis (OA). Similarly, OA is more prevalent among people in occupations characterized by steady, physically demanding activity such as farming, construction, and production-line work. Obesity is a significant risk factor for OA, especially of the knee, Heredity and gender play a role in a person’s likelihood of developing OA, regardless of work or recreational activity.

It is increasingly accepted that most “garden variety” OA results, at least in part, from altered mechanics within the joint. (Certain metabolic conditions such as hemochromatosis and Gaucher disease involve a genetic defect in collagen/cartilage.) Altered mechanics may occur from minor gait abnormalities or major trauma which, over a lifetime, result in repeated stress and trauma to cartilage. Repeated trauma may result in microfracture of cartilage, with incomplete healing due to continuation of the altered mechanics. Disruption of the otherwise smooth cartilage surface allows differential pressure on remaining cartilage, as well as stress on the underlying bone. Debris from fractured cartilage acts as a foreign body, causing low-level inflammation within the synovial fluid. These multiple influences combine to prevent intrinsic efforts at cartilage repair, leading to progressive cartilage destruction and bony joint change. Current thinking suggests the process is not immutable but any intervention would have to be made while the joint is still asymptomatic—an unlikely occurrence.

It is difficult to advise patients on measures to prevent osteoarthritis. Obese persons should lose weight, but few occupational or recreational precautions can be expected to alter the natural history of OA. Altered mechanics may be an important precipitating cause of arthritis but recognizing minor changes, especially within the currently accepted range of normal, makes diagnosis and preventive steps unrealistic.

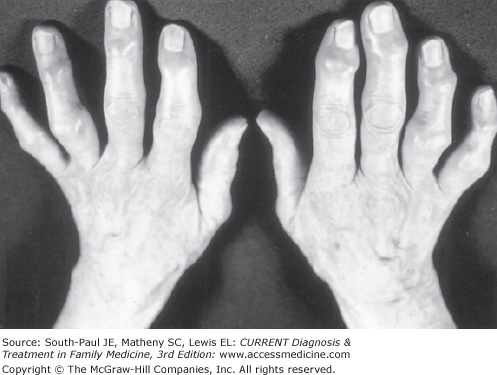

Symptomatic OA represents the culmination of damage to cartilage, usually over many years. OA usually progresses from symptomatic pain to physical findings to loss of function but actually any of these can be first to present. OA can occur at any joint, but the most commonly involved joints are the knee, hip, thumb (carpometacarpal), ankle, foot, and spine. The strongly inherited spur formation at the distal interphalangeal joint (Heberden nodes) and proximal interphalangeal joint (Bouchard nodes) is often classified as OA, yet, although deforming, only infrequently causes pain or disability (Figure 23-1).

Cartilage has no pain fibers, so the pain of OA arises from secondary effects. Osteoarthritic pain is typically associated with movement, meaning that at rest the patient may be relatively asymptomatic. Patient’s awareness that at rest the joint is less painful can be maladaptive. A protective role played by surrounding muscle of both a normal and arthritic joint is that as a “shock-absorber.” Well-maintained muscle can actually reduce mechanical stress on cartilage and bone. But, if patients learn to “favor” the involved joint, disuse of supporting muscle groups may result in relative muscle weakness. Such weakness may result in decrease of the shock-absorber effect, hastening joint damage when stress (eg, walking) resumes. This mechanism also may lead to the complaint that a joint “gives way,” resulting in dropped items (if at the wrist) or falls (if at the knee). In joints with mild OA, pain and instability may counterintuitively improve with exercise or activity.

Advanced OA is characterized by bony destruction and alteration of joint architecture. Secondary spur formation with deformity, instability, or restricted motion is a common finding. Fingers, wrist, knees, and ankles appear abnormal and asymmetric. Warmth and effusion is seen in joints with advanced OA. At this stage, pain may be exacerbated by any movement, weight bearing, or otherwise.

There are few laboratory studies of relevance to the diagnosis of OA. Rarely, the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) will be raised, but only if an inflammatory effusion is present (and even then an elevated ESR or C-reactive protein is more likely to be misleading than helpful). If an effusion is present, arthrocentesis can be helpful in ruling out other conditions (see laboratory findings in gout, later).

OA can be secondary to other conditions, and these diseases have their own laboratory evaluation. Examples include OA secondary to hemochromatosis (elevated iron and ferritin, liver enzyme abnormalities), Wilson disease (elevated copper), acromegaly (elevated growth hormone), and Paget disease (elevated alkaline phosphatase).

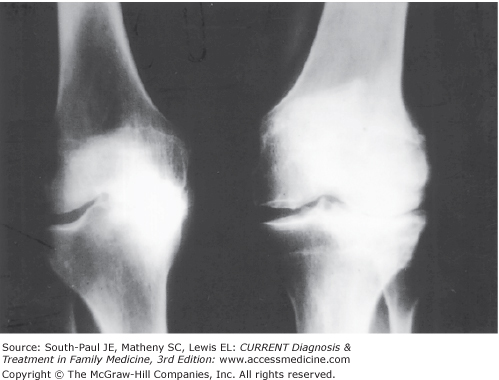

Radiographs are usually not needed for the early diagnosis of OA. Indeed, radiographs may be misleading. Plain films of joints afflicted with OA show changes of sclerosis, thickening, spur formation, loss of cartilage with narrowing of the joint space, and mal-alignment (Figure 23-2). Such radiographic changes typically occur late in the disease process yet do not always correlate with symptoms. Patients may complain of significant pain despite a relatively normal appearance of the joint and, conversely, considerable radiographic damage to a joint may exist with only modest symptoms. In addition, plain film radiography does not provide good information about cartilage, tendons, ligaments, or any soft tissue. Such findings may be crucial to explaining a patient complaint, especially if there is loss of function.

To see cartilage, ligaments, and tendon, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is important and, in many instances, essential. MRI can detect abnormalities of the meniscus or ligaments of the knee, cartilage or femoral head deterioration at the hip, misalignment at the elbow, rupture of muscle and fascia at the shoulder, and a host of other abnormalities. Any of these findings may be incorrectly diagnosed as “OA” before MRI scanning.

Computed tomography (CT) and ultrasonography have lesser, more specialized uses. CT, especially with contrast, can detect structural abnormalities of large joints such as the knee or shoulder. Ultrasonography is an inexpensive means of detecting joint or periarticular fluid, or unusual collections of fluid such as a popliteal (Baker) cyst at the knee.

In practice, it should not be difficult to differentiate among the three prototypical arthritides discussed in this chapter. Nonetheless, Table 23-1 suggests some key differential findings.

| Osteoarthritis | Gout | Rheumatoid Arthritis | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Key presenting symptoms | Pauciarticular. Pain with movement, improving with rest. Site of old injury (sport, trauma). Obesity. Occupation. | Monoarticular. Abrupt onset. Pain at rest and movement. Precipitating event (meal, physical stress). Family history. | Polyarticular. Gradual, symmetric involvement. Morning stiffness. Hands and feet initially involved more than large joints. Fatigue, poorly restorative sleep. |

| Key physical findings | Infrequent warmth, effusion. Crepitus. Enlargement/spur formation. Malalignment. | Podagra. Swelling, warmth. Exquisite pain with movement. Single joint (exceptions: plantar fascia, lumbar spine). Tophi. | Symmetric swelling, tenderness. MCP, MTP, wrist, ankle usually before larger, proximal joints. Rheumatoid nodules. |

| Key laboratory, x-ray findings | Few characteristic (early). Loss of joint space, spur formation, malalignment (late). | Synovial fluid with uric acid crystals. Elevated serum uric acid. 24 h urine uric acid. | Elevated ESR/CRP. Rheumatoid factor. Anemia of chronic disease. Early erosions on x-ray, osteopenia at involved joints. |

A common source of confusion and misdiagnosis occurs when a bursitis-tendinitis syndrome mimics the pain of OA. A common example is anserine bursitis. This bursitis, located medially at the tibial plateau, presents in a fashion similar to OA of the knee, but can be differentiated by a few simple questions and directed physical findings.

Typically, the early development of OA is silent. When pain occurs, and pain is almost always the presenting complaint, the osteoarthritic process has already likely progressed to joint destruction. Cartilage is damaged, bone reaction occurs, and debris mixes with synovial fluid. Consequently, when a diagnosis of OA is established, goals of therapy become control of pain, restoration of function, and reduction of disease progression. Although control of the patient’s complaints is possible, and long periods of few or no symptoms may ensue, the patient permanently carries a diagnosis of OA.

Treatment of OA involves multiple modalities and is inadequate if only a prescription for anti-inflammatory drugs is written. Patient education, assessment for physical therapy and devices, and consideration of intra-articular injections are additional measures in the total management of the patient.

Patient education is a crucial step. The patient must be made aware of the role he or she plays in successful therapy. Many resources are available to assist the provider in patient education. Patient education pamphlets are widely available from government organizations, physician organizations (eg, American College of Rheumatology, American Academy of Family Physicians), insurance companies, pharmaceutical companies, or patient advocacy groups (eg, the Arthritis Foundation). Many communities have self-help or support groups that are rich sources of information, advice, and encouragement.

One of the most effective long-term measures to both improve symptoms and slow progression of disease is weight loss. Less weight carried by the hip, knee, ankle, or foot reduces stress on the involved arthritic joint, decreases the destructive processes, and probably slows progression of disease. Unfortunately, OA makes weight loss more difficult as pain in the joints limits exercise.

On the other hand, exercise is a crucial modality that should not be overlooked. Evaluation for appropriate exercise focuses on two issues: overall fitness and correction of any joint-specific disuse atrophy. One must be flexible in the choice of exercise. Swimming is an excellent exercise that limits stress on the lower extremities. Many older persons are reluctant to learn to swim anew, yet they may be amenable to water aerobic exercises. These exercises encourage calorie expenditure, flexibility, and both upper and lower muscle strengthening in a supportive atmosphere. Stationary bicycle exercise is also accessible to most people, is easy to learn, and may be acceptable to those with arthritis of the hip, ankle, or foot. Advice from an occupational or recreational therapist can be most helpful.

The pain of OA can result in muscular disuse. The best example is quadriceps weakness resulting from OA of the knee. The patient who “favors” the involved joint loses quadriceps strength. This has two repercussions: both cushioning (shock-absorption) and stabilization are lost. The latter is usually the cause of the knee “giving way.” Sudden buckling at the knee, often when descending stairs, is not due to destruction of cartilage or bone but rather to inadequate strength in the quadriceps to handle the load required at the joint. Physical therapy with quadriceps strengthening is highly efficacious, resulting in improved mobility, increased patient confidence, and reduction in pain.

The physical therapist or physiatrist should also be consulted for advice regarding assistive devices. Advanced OA of lower extremity joints may cause instability and fear of falls that can be addressed by canes of various types. Altered posture or joint malalignment can be corrected by orthotics, which has the advantage, when used early, of slowing progression of OA. Braces can protect the truly unstable joint and permit continued ambulation.

The patient wants relief of pain. Despite the widespread promotion of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for OA, there is no evidence that NSAIDs alter the course of the disease. That being the case, NSAIDs are used for their analgesic, rather than anti-inflammatory, effects. Although effective as analgesics, NSAIDs have significant side effects and are not necessarily first-line drugs.

Begin with adequate doses of acetaminophen. Acetaminophen should be prescribed in large doses, 3-4 g/d, and continued at this level until pain control is attained. Once pain is controlled, dosage can be reduced if possible. Maintenance of adequate blood levels is essential and because acetaminophen has a relatively short half-life, frequent dosing is necessary (three or four times a day). High doses of acetaminophen are generally well tolerated, although caution is important in patients with liver disease or in whom alcohol ingestion is heavy.

NSAIDs mixed as a cream or gel and rubbed onto joints have long been advocated for small and even large joint arthritis. There, undoubtedly is less GI upset when delivered in this manner but well-designed studies demonstrating prolonged effectiveness are lacking. There are two FDA-approved products on the US market (diclofenac, ketoprofen), although some compounding pharmacies apparently have more NSAIDs available.

NSAIDs come in two main classes largely based on half-life. NSAIDs with shorter half-lives (eg, diclofenac, etodolac, ibuprofen, and indomethacin) need more frequent dosing than longer acting agents. Several NSAIDs are available in generic or over-the-counter form, which reduces cost. Despite differing pharmacology, there is little difference in efficacy, so choice of medication should be based on individual patient issues such as dosing intervals, tolerance, toxicity, and cost. As with acetaminophen, adequate doses must be used for maximal effectiveness. For example, ibuprofen at doses up to 800 mg three or four times a day should be maintained (if tolerated) before concluding that a different agent is necessary. Examples of NSAID dosing are given in Table 23-2.

| Drug | Frequency of Administration | Usual Daily Dose (mg/d) | Maximal Dose (mg/d) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxaprozin (eg, Daypro) | Every day | 1200 | 1800 |

| Piroxicam (eg, Feldene) | Every day | 10-20 | 20 |

| Nabumetone (eg, Relafen) | One to two times a day | 1000-2000 | 2000 |

| Sulindac (eg, Clinoril) | Twice a day | 300-400 | 400 |

| Naproxen (eg, Naprosyn) | Twice a day | 500-1000 | 1500 |

| Diclofenac (eg, Voltaren) | Two to four times a day | 100-150 | 200 |

| Ibuprofen (eg, Motrin) | Three to four times a day | 600-1800 | 2400 |

| Etodolac (eg, Lodine) | Three to four times a day | 600-1200 | 1200 |

| Ketoprofen (eg, Orudis) | Three to four times a day | 150-300 | 300 |

Since such a major thrust of OA management is pain control, one must recognize the role played by narcotics. Narcotics should be confined to the patient with severe disease incompletely controlled by non-pharmacologic and non-narcotic analgesics, and in whom joint replacement is not indicated. The narcotic medication should be additive to all other measures; for instance, full-dose acetaminophen or NSAIDs should be continued. The patient must be reminded of the fluctuating nature of OA symptoms and not expect complete elimination of pain. Once narcotics are started (in any patient for any cause), most generalist practices institute monitoring measures such as a “drug contract” or referral to a specialist pain management clinic.

Hyaluronic acid (hyaluronan) is a constituent of both cartilage and synovial fluid. Injection of hyaluronic acid, usually in a series of several weekly intra-articular insertions, is purported to provide improvement in symptomatic OA for up to 6 months. It is unknown why hyaluronic acid helps; there is no evidence hyaluronic acid is incorporated into cartilage, and it apparently does not slow the progression of OA. It is expensive and the injection process is painful. Use of these agents (Synvisc, Artzal) is limited to patients who have failed other forms of OA therapy.

Intra-articular injection of corticosteroids has been both under- and overutilized in the past. There is little question that steroid injection rapidly reduces inflammation and eases symptoms. The best use is one in which the patient has an exacerbation of pain accompanied by signs of inflammation (warmth, effusion). The knee is most commonly implicated and is most easily approached. Most authorities recommend no more than two injections during one episode and limiting injections to no more than two or three episodes per year. Benefits of injection are often shorter in duration than similar injection for tendinitis or bursitis, but the symptomatic improvement buys time to reestablish therapy with oral agents.

Until recently, orthopedic surgeons have performed arthroscopic surgery on osteoarthritic knees in an effort to remove accumulated debris and to polish or debride frayed cartilage. However, a clinical trial using a sham-procedure methodology demonstrated that benefit from this practice could be explained by the placebo effect. It remains to be seen if the numbers of these procedures will decline.

Joint replacement is a rapidly expanding option for treatment of OA, especially of the knee and hip. Pain is reduced or eliminated altogether. Mobility is improved, although infrequently to premorbid levels. Expenditures for total joint replacement are likely to increase dramatically as the baby-boomer generation reaches the age at which OA of large joints is more common. Indications for joint replacement (which also applies to other joints, including shoulder, elbow, and fingers) include pain poorly controlled with maximal therapy, malalignment, and decreased mobility. Improvement in pain relief and quality of life should be realized in about 90% of patients undergoing the procedure. Because complications of both the surgery and rehabilitation are increased by obesity, many orthopedic surgeons will not consider hip or knee replacement without at least an attempt by the patient to lose weight. Patients need to be in adequate medical condition to undergo the operation and even more so to endure the often lengthy rehabilitation process. Some surgeons refer patients for “prehabilitation” or physical training prior to the operation. Counseling of patients should include the fact that there often is a 4- to 6-month recovery period involving intensive rehabilitation.

Glucosamine, capsaicin, bee venom, and acupuncture have been promoted as alternative therapies for OA. Glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate are components of glycosaminoglycans, which make up cartilage, although there is no evidence that orally ingested glucosamine or chondroitin sulfate are actually incorporated into cartilage. Studies suggest these agents are superior to placebo in symptomatic relief of mild OA. The onset of action is delayed, sometimes by weeks, but the effect may be prolonged after treatment is stopped. Glucosamine-chondroitin sulfate combinations are available over the counter and are generally well tolerated by patients.

Capsaicin, a topically applied extract of the chili pepper relieves pain by depletion of substance P, a neuropeptide involved in pain sensation. Capsaicin is suggested for tendinitis or bursitis, but may be tried for OA of superficial joints such as the fingers. The cream should be applied three or four times a day for 2 weeks or more before making any conclusion regarding benefit.

Bee venom is promoted in complementary medicine circles. A mechanism for action in OA is unclear. Although anecdotal reports are available, comparison studies to other established treatments are difficult to find. Various vitamins (D, K) and minerals have been recommended, supported, if at all, by poorly controlled studies.

Acupuncture can be useful in managing pain and improving function. There are more comparisons between acupuncture and conventional treatment for OA of the back and knee than for other joints. Generally, acupuncture is equivalent to oral treatments for mild symptoms at these two sites.

Restoring and rebuilding damaged cartilage is theoretically intriguing but not possible at this time. Investigations into regeneration of cartilage, perhaps through pharmaceuticals in conjunction with aggressive orthotic assistive devices, are proceeding. Even so, reversal of the pathophysiologic process in OA is unlikely to be readily available anytime soon. With application of all modalities of treatment—adequate pain control, weight loss, appropriate exercise, orthotics and devices, and surgery—the successful management of osteoarthritis should be realized in most patients.

Gout

- Podagra (intense inflammation of the first metatarsophalangeal joint).

- Inflammation of the overlying skin.

- Pain at rest and intense pain with movement.

- Swelling, warmth, redness, and effusion.

- Tophi.

- Elevated serum uric acid level.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree