Appendectomy and Resection of Meckel’s Diverticulum

The anatomy of the lateral abdominal wall, including the rectus sheath and the right lower quadrant, is described in this chapter. The laparoscopic approach to the appendix and Meckel’s diverticulum is given in Chapter 77.

Steps in Procedure

Make small, obliquely oriented incision over McBurney’s point or over mass (if palpable)

Divide each layer by splitting or incising parallel to fibers

Deliver appendix into wound and confirm diagnosis

Serially clamp and tie appendiceal mesentery

Crush base of appendix with clamp and ligate with 0 chromic

Amputate appendix

Invert stump with purse-string or Z-stitch

Suction and irrigate field

Close incision in layers

If Appendix Appears Normal:

Remove appendix

Run small bowel for at least four feet

Check pelvic organs (female), colon

Further exploration is determined by character of fluid

Hallmark Anatomic Complications

Missed pathology due to small incision when appendix normal

List of Structures

Anterosuperior iliac spine

Umbilicus

McBurney’s point

Camper’s fascia

Scarpa’s fascia

External oblique muscle and aponeurosis

Rectus abdominis muscle

Rectus sheath

Semilunar line

Arcuate line (of Douglas)

Transversus abdominis muscle

Transversalis fascia

Iliohypogastric nerve

Subcostal nerves

Cecum

Appendix

Mesoappendix

Appendicular artery

Ileocolic artery

Ileocecal fold

Meckel’s diverticulum

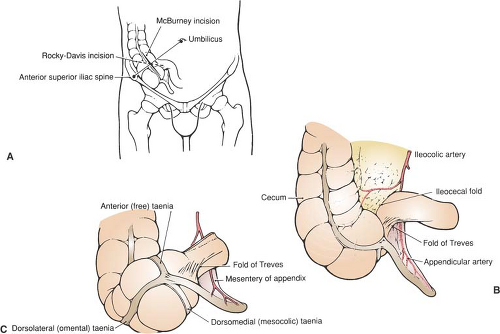

Skin Incision (Fig. 76.1)

Technical Points

Always gently palpate the abdomen after the patient is intubated under anesthesia. You may be able to feel a mass that was inapparent while the patient was conscious and guarding. If a mass is palpable in the right lower quadrant after induction of anesthesia, make the incision over the mass.

More commonly, no mass is felt, and the skin incision is then centered by two fixed anatomic landmarks: the anterosuperior iliac spine and the umbilicus. Draw a line from the umbilicus to the anterosuperior iliac spine. McBurney’s point lies one third of the distance from the anterosuperior iliac spine. The classic McBurney incision is made perpendicular to this line. The incision may be modified to follow the local lines of skin tension, as indicated, but it should pass through McBurney’s point. A Rockey-Davis incision is made over McBurney’s point, but is directed in a nearly transverse direction. This incision yields a good cosmetic result because it parallels Langer’s lines. It also more nearly approximates the direction of the major cutaneous nerves of the region, and it is easy to extend this incision should unexpected pathology be encountered at laparotomy.

Anatomic Points

The anterosuperior iliac spine presents as a prominence in slender individuals, but may take the form of a depression in obese

patients. It is a constant, palpable landmark. The lateral border of the rectus abdominis muscle may be visible as the semilunar line. This begins inferiorly at the pubic tubercle and curves laterally as it ascends. At the level of the umbilicus, the semilunar line is about 7 cm from the midline and lies about halfway between the midline and the side of the body.

patients. It is a constant, palpable landmark. The lateral border of the rectus abdominis muscle may be visible as the semilunar line. This begins inferiorly at the pubic tubercle and curves laterally as it ascends. At the level of the umbilicus, the semilunar line is about 7 cm from the midline and lies about halfway between the midline and the side of the body.

Generally, in this region, one will be able to identify a distinct division of the superficial fascia into two layers: the more superficial layer of fatty areolar tissue, which is Camper’s fascia, and the deeper, membranous layer, which is Scarpa’s fascia.

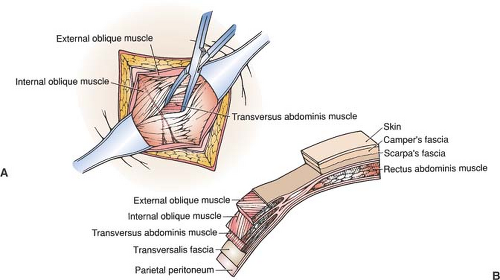

Muscle-Splitting Incision (Fig. 76.2)

Technical Points

The external oblique muscle and its aponeurosis form the first layer of the abdominal wall (which is encountered as the incision is deepened). Open each layer of the abdominal wall by splitting, rather than cutting, the muscular and aponeurotic fibers. The resulting muscle-splitting incision is called a gridiron incision. Because each layer is opened parallel to the muscle fibers and hence in the direction of maximum tension when the fibers contract, the resulting incision is very strong, and hernias are rare.

Medially, the external oblique aponeurosis contributes to the anterior rectus sheath. Usually, the rectus sheath forms the medial boundary of the fascial incision. If necessary, the rectus sheath may be incised. The rectus muscle can then be retracted medially to achieve additional exposure.

Anatomic Points

The fibers of the external oblique muscle run obliquely from above downward, and from lateral to medial (i.e., in the same

direction as you would put your hands into your pockets). Fibers of the external oblique muscle terminate in its aponeurosis following a curved line from the semilunar line to approximately the anterosuperior iliac spine.

direction as you would put your hands into your pockets). Fibers of the external oblique muscle terminate in its aponeurosis following a curved line from the semilunar line to approximately the anterosuperior iliac spine.

The major cutaneous nerves of the region are branches of the iliohypogastric and subcostal nerves.

Deepening the Incision (Fig. 76.3)

Technical Points

Split the fibers of the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles in turn by a combination of sharp and blunt dissection. Incise the fascia with a scalpel, cutting carefully, parallel to the fibers. Extend the cut by inserting partially closed Metzenbaum scissors and pushing, or by splitting bluntly with two fingers or a pair of hemostats. Medially, the sheath of the rectus abdominis muscle limits the extent of the split.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree