All-Hazards Approach To Decontamination

Richard N. Bradley

INTRODUCTION

A terrorist attack with chemical, biological, or radiological hazards may produce a number of contaminated victims. Many of these may arrive at the hospital within minutes of the event. In a multiple casualty situation, vehicles of opportunity, such as police cars, taxicabs, and private autos will transport the majority of casualties. Most of these will not be decontaminated prior to arrival (1). Despite this, most hospitals have not yet implemented adequate plans to decontaminate victims of a large-scale incident (2,3,4,5,6,7).

Since the dose of toxic substances influences the magnitude of the health effects, and since dose is a function of both concentration and time, hospital staff should act to decontaminate victims quickly. The decontamination process must not allow any contaminated individual into the hospital. That could lead to contamination of the building and exposure and possible harm to the hospital staff. Symptomatic staff would not be able to perform their duties and would add to the total number of victims needing treatment. Furthermore, a contaminated hospital may require extensive and costly decontamination.

Many different scenarios may result in contaminated patients arriving at the hospital. Rather than developing one plan for industrial chemicals, another for terrorist use of chemical weapons, another for a radiological incident, and yet another for biological warfare agents, hospitals should adopt an all-hazards approach to medical decontamination. This is important because the predictability, length of forewarning, onset, magnitude, scope, and duration will vary from one incident to the next. An all-hazards approach makes effective use of time, effort, money, and other resources. Furthermore, it helps avoid duplication of effort and gaps in disaster response (8).

As hospitals create an all-hazards plan for decontamination, they should keep three objectives in mind. First, they must not allow any contaminated patients to enter the interior of the hospital. Second, they should decontaminate patients as rapidly as possible. Third, they must plan to protect the hospital decontamination team from secondary exposure and injury.

PREPAREDNESS ESSENTIALS

All hospitals, regardless of size, should plan for providing medical decontamination. Given the widespread presence of hazardous substances and the unexpected nature of terrorist attacks, every hospital is at risk to receive contaminated patients. The ability to provide decontamination is required under national standards and federal law.

One such standard comes from the National Fire Protection Administration (NFPA). Because hospitals have such a vital role in the local response to incidents involving hazardous substances, the NFPA standards require medical facilities to have the ability to perform decontamination. These standards clarify the minimum level of competency required. Hospitals must have a decontamination area with proper ventilation, and plans for restricting access and containing runoff. These standards also require hospitals to provide trained, in-house personnel to decontaminate and care for affected patients. Personal protective clothing must be readily available (9).

Recent revisions to the Joint Commission for Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) standards also address the need for an all-hazards approach to decontamination. JCAHO element of performance 21 from Standard EC.4.10 requires that each hospital’s emergency management plan “identifies means for radioactive, biological, and chemical isolation and decontamination” (10).

Most importantly, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) Hazardous Waste and Emergency Response (HAZWOPER) standard requires hospitals to train workers to perform their anticipated job duties without endangering themselves or others. Federal law does not allow hospitals to deny emergency treatment to anyone who comes to the hospital (11). Thus, all hospitals must be able to care for any contaminated patient who arrives with an emergency medical condition. This requires them to have plans and a trained decontamination team available. It does not require them to train to the same level as hazardous materials teams. Rather, they are required to train decontamination staff to the “first responder operations level,” with emphasis on the use of personal protective equipment (PPE)

and decontamination procedures (12a). In addition to the personnel trained to the operations level, those employees who are likely to witness or discover a hazardous substance release or incident should be trained to the “awareness level”. Additionally, “skilled support personnel” are defined as personnel who are not part of the decontamination or response team but have special skills that are emergently required in the contaminated area. Examples of these persons could be security personnel, specialty physician consultants, and respiratory therapists. Skilled support personnel do not require training in advance of an incident. They must be provided with a preentry briefing and be assisted with donning and doffing their PPE. An on-scene incident commander or decontamination team leader should be on site to coordinate the activities of casualty decontamination. This individual requires additional training beyond the operations level and does not need to be present for decontamination to begin (12b,12c).

and decontamination procedures (12a). In addition to the personnel trained to the operations level, those employees who are likely to witness or discover a hazardous substance release or incident should be trained to the “awareness level”. Additionally, “skilled support personnel” are defined as personnel who are not part of the decontamination or response team but have special skills that are emergently required in the contaminated area. Examples of these persons could be security personnel, specialty physician consultants, and respiratory therapists. Skilled support personnel do not require training in advance of an incident. They must be provided with a preentry briefing and be assisted with donning and doffing their PPE. An on-scene incident commander or decontamination team leader should be on site to coordinate the activities of casualty decontamination. This individual requires additional training beyond the operations level and does not need to be present for decontamination to begin (12b,12c).

ORGANIZE

Local Coordination

One of the key elements in organizing for medical decontamination is to ensure that the hospital is active in planning for the local response to terrorism and other disasters. Hospitals should be equal partners with local government, fire, police, and EMS providers. Communication plans must explicitly describe the process for two-way communication with the local government during the response to a terrorist attack. Rapid alerting after an incident and frequent status updates are vital to a successful operation.

An important forum for coordination of response plans is the Local Emergency Planning Committee (LEPC). Federal statutes require the designation of LEPCs. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Chemical Emergency Preparedness and Prevention Office (CEPPO) coordinates them. Hospitals should play an active role in their LEPC. Plans and exercises should be coordinated through them to allow all parties to gain a mutual understanding of each other’s capabilities and limitations (13).

Incident Command

The medical decontamination area will be organized and controlled as an extension of the Hospital Emergency Incident Command System (HEICS) (14). A medical Decontamination Group supervisor provides overall direction to the Decontamination Group; this individual is also termed the on-scene incident commander or decontamination team leader by OSHA (15). This individual appoints unit leaders to the various functions within the medical decontamination area. Following the principles of HEICS, each individual should have a job action sheet that gives simple instructions on how to carry out assigned responsibilities.

Set-up

Since patients may arrive with only a very brief warning, the Decontamination Group must be able to set up its work area quickly. This requires regular training. The team should establish the decontamination area near an entrance to the hospital. There should be some consideration for protecting patient privacy, such as screens or tents.

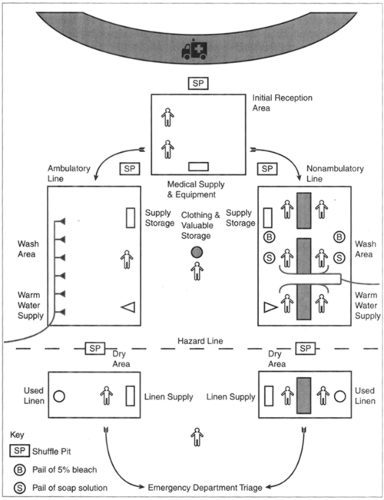

Initial Reception Area

Patients coming to the medical decontamination area will first encounter the initial reception area. The unit leader in this area is responsible to determine which individuals require decontamination, to set decontamination priorities, and to determine the mode of decontamination. This unit leader directs those who can walk independently to a supervised self-decontamination process. Others will require assisted decontamination. It is essential that medical personnel with training in the recognition of clinical toxidromes be located at the initial reception area. These trained providers along with the on-scene incident commander and hazmat personnel will determine what decontamination process will occur.

An immediate treatment area should be located in the initial reception area and may provide lifesaving treatment prior to decontamination. This may be limited to insertion of an oral airway, bag-valve-mask ventilation, control of severe bleeding, and immobilization of the cervical spine. In some cases, providers who have previously practiced the procedures in PPE may insert advanced airways. They may also administer chemical agent antidotes and anticonvulsant medication as needed. Reference charts for chemical agent symptom recognition and treatment may be helpful (16).

The initial reception area should have a plan for dealing with individuals who are armed. This may include victims who are law enforcement officers, civilians in lawful possession of a firearm, and criminals. There is also some risk that a perpetrator could come to the hospital with an improvised explosive device. The initial reception area should have a plan to deal with these contingencies. The plan must allow for a rapid request for assistance from local law enforcement authorities and evacuation of the decontamination area when necessary.

Clothing Removal

The first priority in decontamination is clothing removal. Removing the clothing will usually remove most of the contamination. When clothing is removed it should be placed inside of a plastic bag. The decontamination team will hold the bags until local authorities issue instructions on how to deal with them. Besides being a contamination hazard, the clothing may contain forensic evidence of interest to law enforcement officers. The staff will place patient valuables in another plastic bag. They must mark each bag with a name or number matching it with its owner. One solution is to use a multipart set of wristbands, such as those that nurseries use to match parents and newborn children. Each set of the three or four wristbands has the same number. The person assisting with disrobing places one band on the patient and attaches one to each bag of clothing or valuables. At some point, the decontamination staff may be able to decontaminate some objects, such as metal jewelry, keys and credit cards, and return them to their owners.

Dry Decontamination

In a chemical MCI the greatest number of victims affected may be those exposed to a vapor hazard only. The traditional

approach of washing patients down in showers may not be effective in the face of hundreds or thousands of casualties. The need for wet decontamination of all patients should be assessed in the initial reception area. Victims who have only been exposed to a vapor do not require decontamination beyond the removal of their clothing and replacement with suitable clean clothing. This “dry decontamination” effectively removes any vapor retained in the clothing. A number of commercial products available for dry decontamination allow for the clothing removal while maintaining the victim’s privacy, and the victims can also be shielded and protocols followed to assure safety of their valuables while they are changing clothes. Another type of dry decontamination that may be seen in the literature is the adsorption and physical removal of chemical agents by the use of dry compounds such as diatomaceous earth or the military M291 kit. This process is not commonly used in the civilian setting.

approach of washing patients down in showers may not be effective in the face of hundreds or thousands of casualties. The need for wet decontamination of all patients should be assessed in the initial reception area. Victims who have only been exposed to a vapor do not require decontamination beyond the removal of their clothing and replacement with suitable clean clothing. This “dry decontamination” effectively removes any vapor retained in the clothing. A number of commercial products available for dry decontamination allow for the clothing removal while maintaining the victim’s privacy, and the victims can also be shielded and protocols followed to assure safety of their valuables while they are changing clothes. Another type of dry decontamination that may be seen in the literature is the adsorption and physical removal of chemical agents by the use of dry compounds such as diatomaceous earth or the military M291 kit. This process is not commonly used in the civilian setting.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree