Aging, Death, and Bereavement

It is predicted that, by the year 2020, more than 15% of the population will be more than 65 years of age. In fact, the fastest-growing segment of the population is what has been referred to as the “old-old,” people more than 85 years of age. In Britain, the medical care of the elderly is commonly referred to as “old age medicine.” In the United States, such a descriptor for this group of citizens is avoided. Rather, the care of aging patients is called geriatrics; the study of aging is termed gerontology; and the patients themselves are most commonly referred to as senior or mature citizens. Whatever the terminology, the care of the steadily growing elderly population has become an important branch of medicine.

Although death is an unfortunate reality at any age, most deaths occur in the elderly population. Because of this, a discussion of death and grief, or bereavement, is included in this chapter.

• OLD AGE: 65 YEARS AND OLDER

How can one identify the point at which a middleaged person becomes a senior citizen? The Federal Government defines this milestone as age 65. At about this age, individuals become eligible to collect Federal pension (Social Security) and health insurance (Medicare) (see Chapter 27) benefits, which are funded by monies accrued throughout one’s working life by a combination of employee, employer, and government contributions. The benefits continue until death of the contributor and may, for his spouse and dependents, even continue beyond his death. Because it is the recognized age of retirement from work, 65 years is considered by many to be the transition point where middle age ends and old age begins.

The losses of aging

Americans tend to place a high value on work and independence and on youth and physical beauty (see Chapter 20). Therefore, retired, aging people may be perceived as less valuable. Unfortunately, the loss of social status associated with this perception is only one of the losses the elderly face. They must also deal with loss by death of spouses, family members, and friends; they must confront the inevitable declines in their own health and strength.

Although the losses and changes associated with aging can contribute to the development of depression (see below and Chapter 13) in some people, most elderly people adjust well to these changes and continue to learn, and to contribute to and enjoy life. On the positive side, freedom from the responsibilities of work and childrearing allow older people to pursue interests and education that they did not have time for when they were younger.

Erikson described old age as the stage of ego integrity versus despair; a time when a person either has satisfaction and pride in her past accomplishments or feels that she has wasted her life. It is reassuring for younger people to learn that most elderly people achieve ego integrity in the last years of life.

Independence versus care by others

Many people believe that, invariably, the elderly will ultimately have to be cared for by others. In fact, this is not true. Although aging people in certain cultural groups are typically cared for by relatives (see Chapter 20), less than one-fourth of the American elderly are cared for by younger family members, and fewer than that spend their last years in long-term care facilities like nursing homes (see Chapter 27). In fact, most elderly Americans live independently and care for themselves. Newer options, such as assisted living, in which people live in complexes consisting of private rooms or apartments and receive help with meals, shopping, and housework, allow elderly Americans to remain relatively independent for longer periods of time.

Nursing homes provide inpatient, long-term care for about 5% of the elderly population. This care, often costing more than $1,000 per week, is not covered by Medicare. Therefore, a serious illness or injury that requires long-term inpatient care can effectively pauperize an elderly patient. Federal and State agencies are currently addressing ways of helping the elderly pay for long-term care in nursing homes and assisted living services.

Cognitive function in the elderly

The idea that elderly people invariably have significant cognitive impairment is another pervasive but unsupported stereotype. Although some memory and learning problems may occur in normal aging, they generally do not interfere with the person’s ability to function independently. Dementia, which has been referred to by the now outmoded term “senility,” is a relatively uncommon disorder, occurring in <10% of the total elderly population (see Chapter 18).

The prevalence of dementia does, however, increase with age, and some degree of cognitive impairment is present in up to half of the population over the age of 85. Innovative pharmacological treatments such as the acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and drugs that block the neurotoxic action of glutamate (see Chapter 19) for the most common type of dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, promise that, in the future, these cognitive changes can be prevented or treated effectively.

Longevity

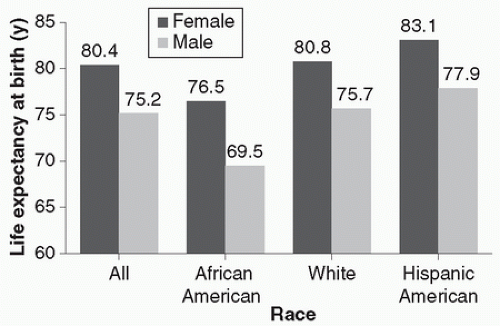

In the United States, the average life expectancy at birth is currently about 77 years. The average life expectancy for men is about 75 years, and for women, it is about 80 years although these figures vary by gender and ethnicity (Fig. 4-1). Although demographic differences in life expectancy have been decreasing over the past few years (African-American men in particular are living longer), they still extend to more than 10 years between white women and African-American men. Longer life expectancy in Hispanic Americans has been attributed to the fact that individuals who immigrate to the United States are among the healthiest from their native countries (Stobbe, 2010). While women tend to live longer than men, this advantage comes with a burden. Elderly women are more likely than elderly men to have disabling health problems.

FIGURE 4-1. Life expectancy (in years) at birth in the United States by sex and ethnic group in 2005-2006. (Data from National Center for Health Statistics, 2008-2009.) |

Research in gerontology suggests that longevity is associated primarily with a family history of longevity. It is also associated with continued physical and occupational activity, work satisfaction, advanced education, and, as discussed in Chapter 3, the presence of social support systems such as marriage.

Physical and neurological changes in aging

It has been said that aging is not for cowards. Physical strength and health gradually decline, and cardiovascular, renal, pulmonary, gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal, and immune functions are ultimately compromised. It is ironic that about the only thing that increases with aging is the ratio of body fat to muscle mass.

Neurological changes that occur in normal aging include decreased cerebral blood flow and decreased brain weight. Amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles may also appear, although to a lesser extent in normally aging brains than in brains of patients with Alzheimer’s disease (see Chapter 18). Despite these brain changes, which can be accompanied by mild reductions in memory and learning speed, intelligence (in the absence of dementia or other brain disease; see Chapter 10) remains approximately the same throughout life.

Neurotransmitter availability in the brain decreases with age. This decrease occurs via several mechanisms. First, secretion of the major behavioral neurotransmitters diminishes. Also, concentration of monoamine oxidase increases, leading to the accelerated breakdown of some of these neurotransmitters. Finally, neurotransmitter receptors may be less responsive in the aging brain. The clinical consequences of these changes in neurotransmitter availability in the elderly can include increased likelihood of psychiatric symptoms (Table 4-1) and of negative side effects associated with psychopharmacological treatment.

table 4.1 NEUROCHEMICAL CHANGES IN THE AGING BRAIN | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Psychosocial changes in aging

The common physical health problems associated with aging not only are uncomfortable, but they can have serious emotional and social consequences. For example, the embarrassing problem of reduced bladder control seen in some aging patients can impair one’s ability to leave home. Age-associated losses in muscle strength and in sensory functions like vision and hearing can further decrease social opportunities and increase social isolation, wellknown contributors to the occurrence of depressive symptoms in people of any age.

Another, often undetected, serious social problem associated with aging is the abuse of cognitively or physically impaired elderly people by their caretakers (see Chapter 22).

Psychopathology in the elderly

Depression in the elderly is commonly characterized by memory loss and cognitive problems. These symptoms can mimic and thus be misdiagnosed as dementia. This misdiagnosed disorder, known as pseudodementia (see Chapter 18

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree