Advancement and Rotational Flaps

Jeffrey H. Kozlow

DEFINITION

Advancement and rotational flaps are tissue transfer techniques used in reconstructive surgery for the closure of acquired defects.

A flap is an area of tissue designed for movement to another area while remaining vascularized. This is in contrast to a graft, which is transferred in a nonvascularized fashion and becomes revascularized only with local incorporation and vascular neogenesis.

Advancement and rotation flaps are both considered local flaps because they borrow from the tissue adjacent to the defect. Distant flaps use tissue from areas away from the defect, and free flaps involve the transfer of tissue from a distant site by means of a microsurgical anastomosis.

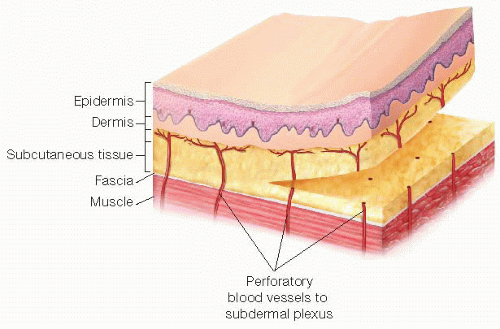

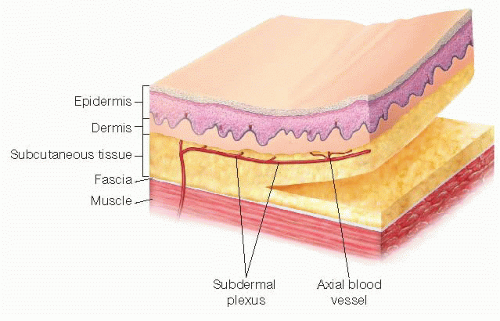

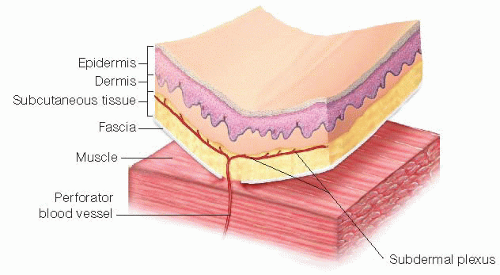

Local flaps can be defined by their vascularity. Random flaps are based on blood flow through the subdermal plexus to provide vascularity to the distal end of the flap (FIG 1). Axial flaps are based on a longitudinal blood vessel incorporated into the flap design that can extend the effective length of a flap (FIG 2). Perforator flaps are based on underlying septocutaneous or musculocutaneous perforators into the central area of the flap (FIG 3).

Local flaps can also be defined by the geometry of the incisions used with example of common designs shown in the following text.

Flap design includes evaluation of tissue laxity, optimization of scar position, and management of standing cutaneous deformities.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

The choice and design of local flaps is dependent on multiple factors including the region on the body for reconstruction, local and regional soft tissue laxity, relationships with underlying critical anatomy, relaxed lines of skin tension for scarring, and underlying flap vascularity.

Poor quality of tissue adjacent to the defect may preclude the use of local flaps.

Local radiation damage will often limit the pliability of tissues for transfer and inhibit the healing potential of tissue.

Each patient is different and flap choice must be tailored to the individual, the size of the defect, and the location of the defect.

There are often multiple different flaps that will adequately reconstruct a defect; there is no “one right answer” for any given case.

Flap design should also consider potential oncologic implications including the need for recurrence monitoring, secondary reconstruction techniques, and margin management when reconstruction is done immediately after resection and margin status cannot be confirmed.

For patients with lower extremity defects, an evaluation of arterial status and venous insufficiency should be considered.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

In general, local flaps do not require preoperative imaging or diagnostic studies.

Doppler can be used to identify either axial or perforating blood vessels if clinically indicated.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Preoperative Planning

A reconstructive plan can only be made after the resection is designed. In cases that may require a plastic and reconstructive surgeon for advanced reconstructive techniques, it is always best to plan accordingly ahead of time and not consult intraoperatively.

Preoperative markings may include important regional anatomic landmarks (such as facial rhytids) that may be obscured with the injection of local anesthetic intraoperatively.

Positioning

Patients should be positioned to optimize not only surgical access for tumor resection but also for access to any local areas potentially usable for the subsequent reconstruction.

All areas should be prepped widely to allow for access to all local and regional flap option. All extremities should be prepped and draped circumferentially. For areas where symmetry is important (such as the face or breasts), it is important to have the contralateral side in the operative field as well.

TECHNIQUES

There are multiple local flaps that are available for use in reconstruction. Not all of them can be highlighted in this text; however, the most common flaps for general reconstruction are described in the following text. In some cases, multiple local flaps are required and techniques can be combined to achieve closure of the defect.

In most flaps, the area is often infiltrated with local anesthesia including 1:100,000 to 1:200,000 parts epinephrine to help with hemostasis and minimize electrocautery injury to dermal edges. However, overinjection of local anesthesia can result in tissue edema that decreases flap mobility.

Skin hooks are used on the margins of a flap for handling; the use of forceps is discouraged due to injury to the flap edges from overzealous pressure.

Drains are typically not used unless flaps are large.

Flaps designed around joints should be inset under the greatest tension of the joint to avoid postoperative dehiscence.

SIMPLE ADVANCEMENT FLAPS

Flap Design

Based on either the subdermal plexus as a vascular supply from the base of the flap to the distal end or can include an axial vessel for additional length and degrees of freedom

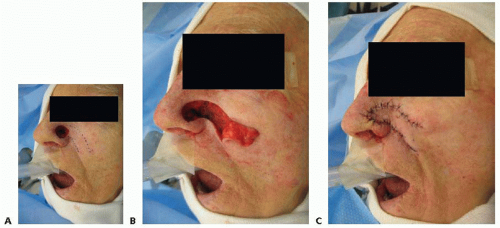

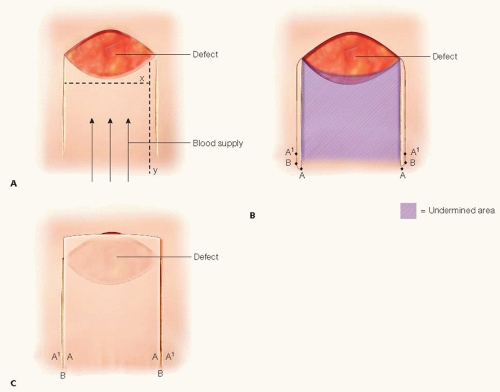

Incisions are designed in a parallel fashion equal to the dimensions of the defect (FIGS 4A and 5A); choice of direction is based on local tissue laxity.

Classic teaching is that a maximum 3:1 ratio of length to width can be used when the flap is based on the subdermal plexus.

Flap Elevation

Incisions are made extending from the defect in a parallel fashion toward base of flap.

Dissection is carried down to the depth of defect or deeper in order to match volumetric dimensions of reconstruction.

Defect Closure

Careful hemostasis is assured after flap elevation; hematomas under the flap can compromise vascularity and overall outcome.

Once flap has adequate advancement to fill defect, closure often occurs from the base of the flap to help “push” the flap into the defect, which can help alleviate tension over the distal closure (FIG 4C).

Standing cutaneous deformities can occur as the base is advanced. These areas can be resected with a scar perpendicular to the direction of the flap.

Dermal closure is performed using an absorbable suture followed by either a subcuticular or simple external suture (FIG 5C).

FIG 4 • The design of an advancement flap is based on subdermal blood supply from the base of the flap. The initial parallel incisions are drawn from the wound edges (A). The advancement flap is undermined toward the base, leaving only the subdermal blood supply to vascularize the distal tip (B). The flap is then advanced forward and pushed into the defect. The previous base corner of the flap (point A) has been pushed forward and is approximated to point A1 (C). |

ROTATIONAL/TRANSPOSITION FLAPS