An aneurysm is defined as a permanent, focal dilation of an artery to a size that is greater than 50% of the normal or expected transverse diameter of the vessel. Although dimensions differ slightly for men and women, practically speaking the normal diameter for the abdominal aorta is 2 cm; therefore, the abdominal aorta is considered aneurysmal when it reaches 3 cm in transverse dimensions.

Fusiform aneurysms are the most common configuration and are a symmetric enlargement of the entire vessel, whereas a saccular aneurysm is a focal outpouching that results in an asymmetric bulge of the vessel wall.

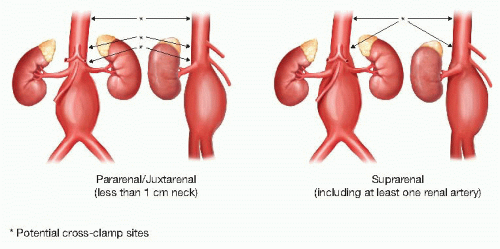

Aneurysms may occur in virtually any vessel in the body but are most commonly seen in the infrarenal abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA). The neck is the length of normal aorta between the osteum of the lowest renal artery and the beginning of the aneurysmal aorta. The term juxtarenal is used to describe AAAs that do not involve the renal arteries but because of proximity (<1 cm neck) require clamping above the renal arteries to complete the proximal aortic anastomosis. In a suprarenal aneurysm, at least one of the renal arteries arises from aneurysmal aorta, implying the need not only for a proximal clamp but also renal artery reconstruction at the time of the repair (FIG 1). This chapter will focus on the indications and techniques for repair of infrarenal and juxtarenal AAA.

AAA size and/or expansion rate is an important predictor of rupture, and as such guides indication for repair in asymptomatic patients.1

A thorough history and physical exam is imperative in the evaluation of a patient being considered for aneurysm repair.

History of present illness: Determine how the aneurysm was discovered. Often, AAAs are an incidental discovery on an imaging test done for another purpose. Be sure to ask about abdominal or back pain, which may indicate this is a symptomatic aneurysm that would require more urgent repair.

Past medical history: Patients with concomitant renal, cardiac, or lung disease tend to have more complications perioperatively and should be medically optimized prior to proceeding with elective repair. Although there is no benefit to preoperative cardiac revascularization in asymptomatic patients, those with known cardiac disease or risk factors should be evaluated by a cardiologist.6

Family history: Close to 15% of patients with AAA will have a first-degree relative with aneurysmal disease. Patients with AAA should be counseled to alert their siblings and children to this condition, so they may be screened appropriately.3

Social history: Smoking has been linked to increased risk of aneurysm formation and rate of expansion. Patients should be counseled on smoking cessation.

Review of systems: In addition to the generalized systems review appropriate for all patients undergoing major surgery, particular attention should be directed to other vascular comorbidities. In particular, query about previous cerebrovascular accident (CVA) or transient ischemic attack (TIA) symptoms, amaurosis fugax, mesenteric ischemia, lower extremity ischemic symptoms (claudication, rest pain, ulcers), and work up positive symptoms as appropriate.

On physical exam, perform a thorough abdominal exam, although be aware that the positive predictive value for localizing a small- to moderate-sized AAA on exam is poor.

A small proportion (1% to 10%) of patients with AAA will have a concomitant aneurysm elsewhere, so be cognizant that those patients with known AAA and a prominent femoral or popliteal pulse may need further imaging to exclude an aneurysm in these locations.7

Of all imaging techniques used for AAA surveillance, B-mode ultrasonography is the least expensive and does not expose the patient to radiation. Currently, the U.S. Preventative Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends an ultrasound as a screening test for males between the ages of 65 and 75 years who have ever smoked 100 or more cigarettes over a lifetime. There are no official recommendations for women. It is generally accepted that a negative screening ultrasound exonerates the patient from further screening or surveillance imaging, as the likelihood of new aneurysm development of clinical significance after the age of screening is extremely low. If a screening ultrasound detects a small aneurysm, yearly ultrasounds are indicated until the sac approaches a size where repair may be indicated, at which time further imaging with computed tomography (CT) is recommended.7,9

Computed tomography angiography (CTA) provides a more accurate assessment of aneurysm size, extent, branch vessel proximity and involvement (which may determine if the aneurysm is amenable to endovascular or open repair, and if open repair is to be done, where the proximal clamp should be applied) and is the test that should be used for planning open AAA repair. A thorough exam should include thin (1.5 cm or smaller) cuts of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis with contrast administered in the arterial phase (FIG 2).

It is important to note the location of the aneurysm and its relationship to the renal arteries. Renal anatomy should be noted as well, including any accessory renal arteries and the presence of a pelvic or horseshoe kidney. The renal vein usually travels anterior to the aorta but can be posterior and this should be noted as it may influence operative approach. Other venous anatomy such as a duplicated or left-sided inferior vena cava (IVC) should be noted as well.

The decision to operate on an asymptomatic patient is based on three primary factors: the risk of the aneurysm’s rupturing, the risk associated with aneurysm repair, and the patient’s life expectancy. The operative risk and overall life expectancy should be assessed. Assuming that a patient is fit enough to proceed with repair, size is currently our best predictor of rupture. The UK Small Aneurysm Trial and ADAM VA Trial recommend treatment for all patients with an infrarenal AAA larger than 5.5 cm in size, with consideration for repair in women with AAA of 5.0 cm given their higher risk of rupture and likely smaller baseline aortic size. These studies also support repair for those patients who have an increase in diameter of greater than 0.5 cm over a 6-month period (Table 1).10,11

Although there are no large trials looking specifically at iliac aneurysms, repair is generally recommended when they reach 4 cm or greater in size. Iliac aneurysms are more often seen in patients with a concomitant aortic aneurysm and only a quarter of patients with iliac aneurysms will have isolated disease.

All open repairs should be performed under general anesthesia. It is preferable for the anesthesia team to evaluate the patient prior to the day of surgery so that appropriate time for developing an anesthetic plan, lines, and other means of hemodynamic monitoring is allowed. The use of an epidural for pain control in the postoperative period is useful. In addition, arrangements should be made for autotransfusion given the unavoidable amount of intraoperative blood loss.

Preoperative understanding of anatomy is of the utmost importance. The surgeon must understand the proximity of the aneurysmal aorta to the renal and visceral vessels and if these branch vessels are affected, as this will impact where the proximal cross-clamp will be applied. If at all possible, clamping should only be done on nonaneurysmal aorta with minimal thrombus or calcification to minimize risk of distal embolization of debris or clamp injury, and all aneurysmal aorta should be resected even if this means involvement of the visceral or iliac segment. If the aorta contains a significant amount of debris or there is little space between branch vessels, a more proximal clamp site in the supraceliac aorta should be considered. It is important to discuss the proposed clamp site with anesthesia preoperatively, as this will affect their management of the patient. The choice of clamp site should be made during the preoperative stage, as the intraoperative need to move the clamp higher is associated with adverse outcomes.

Table 1: Indications for Repair of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm

• Leak or frank rupture

• Size (5.5 cm in males, 5 cm in females for aortic aneurysm, 4 cm for iliac aneurysms)

• Increase in size of >0.5 cm over a 6-month period

• Symptomatic (pain, compression on adjacent structures)

• Dissection within aneurysm

Planning for the distal anastomosis requires review not only of the aortic bifurcation but the iliacs as well. If there is aneurysmal or occlusive disease within the iliac arteries, concurrent repair with a bifurcated graft may be appropriate; otherwise, the majority of AAAs are repaired with a tube graft to the iliac bifurcation. Anastomosis may predicate method of distal control, which can be obtained with a single clamp across the bifurcation or both iliac origins, or occlusion balloons (Foley catheters or Pruitt occlusion balloons) for heavily diseased vessels.

Key pre-operative planning concerns are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2: Operative Planning | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|