Adrenalectomy: Open Anterior

Barbra S. Miller

DEFINITION

Adrenal masses may be functional or nonfunctional and benign or malignant. Most are incidentally discovered when imaging is obtained for other reasons. Laparoscopic adrenalectomy is the gold standard for appropriately sized benign (most often functional) adrenal masses and for some metastatic tumors to the adrenal gland (see Part 5, Chapters 49 and 50). If adrenocortical carcinoma is a concern, adrenalectomy by an open approach should be performed.1 Several genetic syndromes are associated with adrenal abnormalities and appropriate testing should be obtained if indicated.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Adenoma

Metastatic cancer

Pheochromocytoma

Ganglioneuroma

Primary adrenocortical carcinoma

Cyst

Adjacent paraganglioma

Soft tissue tumor

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

All adrenal abnormalities should be evaluated in a systematic fashion, including a thorough history and physical examination investigating the possibility of a hormone-secreting mass. This includes the possibility of a pheochromocytoma, Cushing’s syndrome, primary hyperaldosteronism, and hypertestosteronemia. Specifically, the patient should be questioned regarding poorly controlled hypertension, diabetes, edema, diaphoresis, tachycardia, palpitations, sudden severe headaches, flushing, and easy bruising. The physical exam should look for evidence of central obesity, edema, peripheral wasting, core muscle weakness, a buffalo hump, striae, thin skin, and facial plethora. Because the adrenal gland is situated in the retroperitoneum, unless it is extremely large, palpation of the mass is usually unable to be achieved.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

All adrenal masses should undergo appropriate biochemical testing. Even in the absence of signs or symptoms, patients should have at a minimum the following: potassium, aldosterone, renin, plasma fractionated metanephrines (followed by 24-hour urine metanephrines and normetanephrines, catecholamines, and vanillylmandelic acid [VMA] if plasma values are abnormal), 24-hour urine-free cortisol, and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). Some physicians may also perform a low-dose dexamethasone suppression test and obtain dehydroepiandrosterone-sulfate (DHEA-S) and free testosterone, among other laboratory tests.

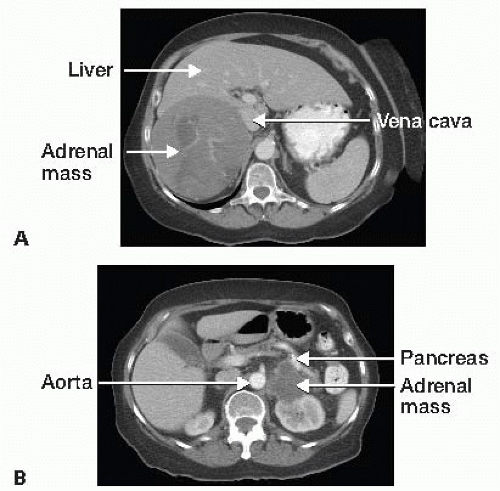

Imaging studies should include an adrenal protocol computed tomography (CT) scan (to assess imaging characteristics and calculate washout percentage of contrast from the tumor) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (to assess for loss of signal intensity between in and out of phase images) and a positron emission tomography (PET) scan if malignancy is questioned (FIG 1).

Additional imaging studies may be required depending on the functionality of the tumor (metaiodobenzylguanidine [MIBG] for pheochromocytoma in select cases, adrenal vein sampling for hyperaldosteronism, etc.).

Fine needle aspiration or core biopsy is not recommended if adrenocortical carcinoma is suspected but may be useful if metastasis to the adrenal gland is in the differential and the adrenal tumor is the most accessible site of metastasis for biopsy in the setting of multiple sites of metastatic disease. If biopsy is performed, it is imperative to first biochemically rule out a pheochromocytoma.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Adrenal tumors, if benign appearing by imaging criteria, nonfunctional, and therefore not requiring resection, should be reevaluated with at least one additional CT scan or MRI 6 to 12 months after the initial imaging study to ensure stability in size and internal imaging characteristics. Some advocate for a longer period of follow-up imaging for 2 years with reevaluation of biochemistry for 4 more years.2 Functional tumors leading to hormone excess, indeterminate masses, and those suspected of being adrenocortical carcinoma or isolated metastatic disease from another primary tumor without evidence of widespread metastatic disease should be removed.

FIG 1 • A. CT scan showing large heterogeneous right adrenal mass concerning for adrenocortical carcinoma. B. CT scan showing a large left adrenal mass. |

Preoperative Planning

The surgeon must evaluate available imaging studies for tumor involvement of adjacent organs, vessels, and lymphadenopathy. Invasion of major vessels (vena cava) or adjacent organs may require additional teams or different approaches to the tumor. As CT tends to overestimate invasion of adjacent vessels, MRI with magnetic resonance venogram can be especially helpful to assess for vena cava invasion or intracaval tumor thrombus.

The risks, benefits, and alternatives to surgery are discussed with the patient, including potential need for steroid supplementation in the postoperative setting. Patients with pheochromocytomas should be adequately alpha blocked and volume replete. Beta blockade may also be necessary. In patients with hyperaldosteronism, a potassium level should be checked the morning of surgery and treated if necessary.

Routine prophylactic antibiotics and deep vein thrombosis (DVT) prophylaxis is administered prior to surgery, and sequential compression devices are applied.

A general endotracheal anesthetic is administered and an epidural is often placed for postoperative pain management.

Common to all approaches, skin preparation with clipping rather than shaving is preferred, and the surgical area is prepped and draped in a sterile fashion.

Positioning

The patient is placed supine on the table with arms out to the side, and all pressure points are padded appropriately (FIG 2).

TECHNIQUES

RIGHT ADRENALECTOMY

Exposure

A wide right subcostal incision is made and carried across the midline to the midleft abdomen. The subcutaneous fat, fascia, abdominal wall musculature, and posterior fascia are incised with cautery. The peritoneum is entered sharply with scissors and the incision opened to its full length. The ligamentum teres is divided between sutures and the peritoneal cavity is inspected in a systematic manner, assessing for evidence of metastatic disease or other abnormalities. The falciform ligament, triangular, and coronary ligaments of the left and right lobes of the liver are divided to allow for full mobility of the liver during retraction (FIGS 3 and 4).

Ultrasound of the liver is also performed to assess for metastatic disease not identified on preoperative imaging, and the vena cava may also be evaluated sonographically for evidence of intracaval tumor thrombus or direct tumor invasion.

The hepatic flexure of the colon may need to be mobilized, and if a Kocher maneuver is needed, it should be done at this time. The right lobe of the liver is retracted medially to expose the retroperitoneum and allow access to the area of the tumor and vena cava. A retractor system is placed. The Omni retractor provides excellent retraction as well as the critically important ability to retract the costal margin and ribs as superiorly and anteriorly as possible. A large saline-soaked towel is placed against the bowel with retractors to not only provide exposure but also to exclude the rest of the peritoneal cavity and minimize potential seeding of the peritoneal cavity by a malignant tumor (FIG 5).

Dissection

The posterior peritoneal lining over the retroperitoneum is incised over the superior half of the right kidney and carried from medial to lateral out to the side of the abdominal wall. Medial dissection should proceed carefully to the vena cava, making sure not to divide branches of the renal artery supplying the upper portion of the kidney or venous branches draining to the renal vein. Small branches supplying and draining the adrenal gland should be carefully ligated and divided. Any lymph nodes posterior to the renal hilum should be included in the dissection (FIGS 6 and 7).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree