INTRODUCTION

Access to health care is the ability to obtain health services when needed. Lack of adequate access for millions of people is a crisis in the United States.

Access to health care has two major components. First and most frequently discussed is the ability to pay. Second is the availability of health care personnel and facilities that are close to where people live, accessible by transportation, culturally acceptable, and capable of providing appropriate care in a timely manner and in a compatible language. The first and longest portion of this chapter dwells on financial barriers to care. The second portion touches on nonfinancial barriers. The final segment explores the influences other than health care (in particular, socioeconomic status and race/ethnicity) that are important determinants of the health status of a population.

FINANCIAL BARRIERS TO HEALTH CARE

In 1990, Ernestine Newsome was born into a low-income working family living in South Central Los Angeles. As a young child, she rarely saw a physician or nurse and was behind on her childhood immunizations. When Ernestine was 7 years old, her mother began working for the telephone company, and this provided the family with health insurance. Ernestine went to a neighborhood physician for regular checkups. When she reached 19 in 2009, she left home and began work as a part-time secretary. She was no longer eligible for her family’s health insurance coverage, and her new job did not provide insurance. She has not seen a physician since starting her job.

Health insurance coverage, whether public or private, is a key factor in making health care accessible.

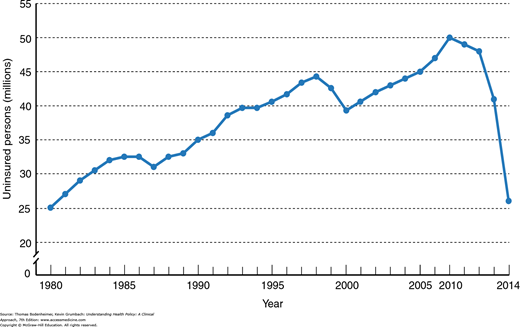

Historically, trends in health insurance coverage in the United States in the modern era can be divided into three phases. The first phase, occurring between the 1930s and mid-1970s, saw a large increase in the proportion of Americans with health insurance due to the growth of employment-based private health insurance and the 1965 passage of Medicare and Medicaid (Table 3–1). The second phase, starting in the late 1970s, marks a reversal of this trend; between 1980 and 2010, the number of uninsured people in the United States grew from 25 to 50 million. The single most important factor explaining the growing number of uninsured in this period was a decrease in private insurance coverage. The number of uninsured peaked in 2010—the year the ACA was signed into law–signifying the onset of the third phase in this historical trend as the number of uninsured decreased from 50 to 41 million between 2010 and 2013 (Fig. 3-1). Because the major coverage expansion policies legislated by the ACA did not take effect until 2014, the decrease in the number of uninsured between 2010 and 2013 was largely explained by states more actively enrolling individuals and families eligible for Medicaid under the traditional eligibility criteria. In 2014, upon implementation of the ACA’s private insurance mandates and voluntary state Medicaid expansion, the number of uninsured individuals decreased further from 41 to 26 million (Carman et al., 2015). Even if the ACA is fully implemented, about 20 million people will remain uninsured due to states not participating in Medicaid expansion, individuals opting out of the individual mandate, individuals not enrolling in Medicaid even when eligible, and undocumented immigrants remaining ineligible for Medicaid and insurance subsidies.

| Number of People (millions) | Population (%) | |

| Medicare a | 52 | 17 |

| Medicaid | 51 | 16 |

| Employment-based private insurance | 150 | 47 |

| Individual private insurance | 22 | 7 |

| Uninsured | 41 | 13 |

| Total United States population | 316 |

Joe Fortuno dropped out of high school and went to work for Car Doctor auto body shop in 2003. His employer paid the full cost of health insurance for Joe and his family. Joe’s younger cousin Pete Luckless got a job working at an auto mechanic shop in 2005. The company did not offer health insurance benefits. In 2008, Car Doctor, after experiencing a doubling of health insurance premium rates over the prior few years, began requiring that its employees pay $150 per month for the employer-sponsored health plan. Joe could not afford the monthly payments and lost his health insurance.

The major factor precipitating the crisis of uninsurance in the United States was the erosion of private insurance that commenced in the late 1970s. Three principal factors undermined private health insurance coverage:

The skyrocketing cost of health insurance made coverage unaffordable for many businesses and individuals. From 2000 to 2014, employer-sponsored family health insurance premiums rose by 160%. In 2014, the average annual cost of health insurance, including employer and employee contributions, was $6,025 for individuals and $16,834 for families. Some employers responded to rising health insurance costs by dropping insurance policies for their workers. Many employers shifted more of the cost of health insurance premiums and health services onto their employees, resulting in employees dropping health coverage because of unaffordability. In 2014, the average employee paid 29% of the employer-sponsored family premium, though some employees paid as much as 44%. Low-income workers have been hit especially hard by the combination of rising insurance costs and declining employer subsidies (Claxton et al., 2014).

Jean Irons worked for Bethlehem Steel as a clerk and her fringe benefits included health insurance. Bethlehem Steel was bought by a global corporation and her plant moved to another country. She found a job as a food service worker in a small restaurant. Her pay decreased by 35%, and the restaurant did not provide health insurance.

The economy in the United States has undergone a major transition. The number of highly paid, largely unionized, manufacturing workers with employer-sponsored health insurance has declined, and the workforce has shifted toward more low-wage, nonunionized service and clerical workers whose employers are less likely to provide insurance. Between 1960 and 2007, the number of workers in the manufacturing sector decreased from 30% to 10% of all nonfarm workers while the number of workers working in the service sector rose from 65% to 83%. From 1957 to 2010, the percentage of workers with part-time jobs—generally without health benefits—increased from 12% to 20%.

These two factors—increasing health care costs and a changing labor force—eroded private insurance coverage. A countervailing trend has been a major expansion of public insurance coverage through Medicaid, the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP), and the ACA. Without these changes, many more millions of Americans would currently be uninsured.

Sally Lewis worked as a receptionist in a physician’s office. She received health insurance through her husband, who was a construction worker. They got divorced, she lost her health insurance, and her physician employer told her that he could not provide her with health insurance because of the cost.

The link of private insurance with employment inevitably produces interruptions in coverage because of the unstable nature of employment. People who are laid off from their jobs or who leave jobs because of illness may also lose their insurance. Family members insured through the workplace of a spouse may lose their insurance in cases of divorce, job loss, or death of the working family member. People who leave their employment may be eligible to pay for continued coverage under their group plan for 18 to 36 months, as stipulated in the Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1985 (COBRA), with the requirement that they pay the full cost of the premium; however, many people cannot afford the premiums, which may exceed $1,000 per month for a family. The ACA provides a lower-cost alternative to COBRA.

The often transient nature of employment-linked insurance is compounded by difficulties in maintaining eligibility for Medicaid. Small increases in family income can mean that families no longer qualify for Medicaid. The net result is that many people cycle in and out of the ranks of the uninsured every month. Health insurance may be a fleeting benefit.

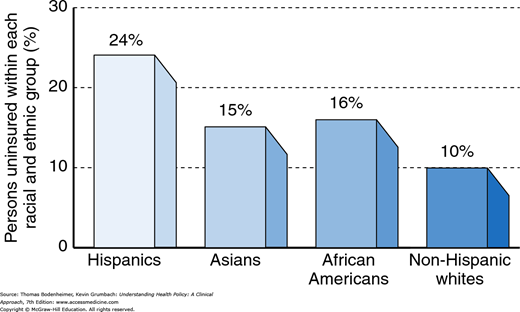

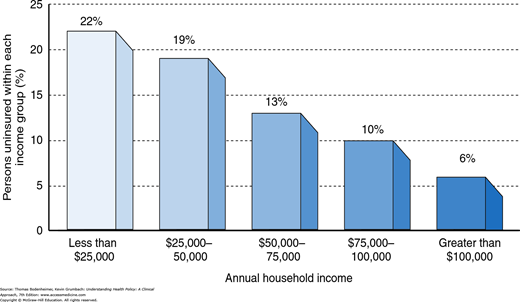

In 2013, prior to the first year of full implementation of the ACA, 10% of non-Latino whites were uninsured, compared with 16% of African Americans, 15% of Asians, and 24% of Latinos (Fig. 3-2). Twenty-two percent of individuals with annual household incomes less than $25,000 were uninsured, compared with 6% of individuals with household incomes of $150,000 or more (Fig. 3-3) (U.S. Census Bureau, 2014).

Morris works for a corner grocery store that employs five people. Morris once asked the owner whether the employees could receive health insurance through their work, but the owner said it was too expensive. Morris, his wife, and their three kids were uninsured until 2014 when they obtained tax-subsidized private insurance under the ACA.

Norris, a shipyard worker in Miami, was laid off in 2009 at age 55 and was unable to get another job. When he became unemployed and lost his employer-sponsored private insurance, he was ineligible for Medicaid because he was not a parent, not older than 65, and not disabled. He was disappointed when Florida decided not to expand Medicaid under the ACA. Because his income is 41% of the Federal Poverty Level, he is not eligible for ACA private insurance subsidies, and yet he remains ineligible for Florida’s Medicaid program. He continues to be uninsured.

Prior to the ACA, the uninsured were divided into two major categories: the employed uninsured (Morris) and the unemployed uninsured (Norris). Seventy-five percent of the uninsured were employed or the spouses and children of those who work. Most of the jobs held by the employed uninsured were low paying, in small firms, and may be part time. Twenty-five percent of the uninsured were unemployed, often with incomes below the poverty line, but like Norris were ineligible for Medicaid.

Two US senators are debating the issue of access to health care. One, who voted for the ACA, decries the stigma of uninsurance and claims that people without insurance receive less care and suffer worse health than those with insurance. The other, who is trying to repeal the ACA, disagrees, claiming that hospitals and physicians deliver large amounts of charity care, which allows uninsured people to receive the services they need.

To resolve this debate, many research studies conclusively show that people lacking health insurance receive less care and have worse health outcomes (Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, 2014).

Percy, a child whose parents were both employed but not insured, was refused admission by a private hospital for treatment of an abscess. Outpatient treatment failed, and his mother attempted to admit Percy to other area hospitals, which also refused care. Finally an attorney arranged for the original hospital to admit the child; the parents then owed the hospital $6,000.

Access to health care is most simply measured by the number of times a person uses health care services. Commonly used data are numbers of physician visits, hospital days, and preventive services received. In addition, access can be quantified by surveys in which respondents report whether or not they failed to seek care or delayed care when they felt they needed it. In 2013, 53% of uninsured adults, compared with 11% of those with private insurance, had no usual source of care, 34%, compared with 7% of those with private insurance, postponed seeking care due to cost, and 30%, compared with 4% for those with private insurance, went without needed care due to cost (Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, 2014).

Dan Coverless noticed that he was urinating a lot and feeling weak. His friend told him that he had diabetes and needed medical care, but lacking health insurance, Mr. Coverless was afraid of the cost. Eight days later, his friend found him in a coma. He was hospitalized for diabetic ketoacidosis.

Penny Evans worked in a Nevada casino. She was uninsured and ignored a growing mole on her chest. After many months of delay, she saw a dermatologist and was diagnosed with malignant melanoma, which had metastasized. She died 2 years later at the age of 44.

Leo Morelli, a hypertensive patient, was doing well until his company relocated to Mexico and he lost his job. Lacking both paycheck and health insurance, he became unable to afford his blood pressure medications. Six months later, he collapsed with a stroke.

The uninsured suffer worse health outcomes than those with insurance. Compared with insured persons, the uninsured like Mr. Coverless have more avoidable hospitalizations; like both Mr. Coverless and Ms. Evans, they tend to be diagnosed at later stages of life-threatening illnesses, and they are on average more seriously ill when hospitalized. Higher rates of hypertension and cervical cancer and lower survival rates for breast cancer among the uninsured, compared with those with insurance, are associated with less frequent blood pressure screenings, Pap smears, and clinical breast examinations (Ayanian et al., 2000). People without insurance have greater rates of uncontrolled hypertension, diabetes, and elevated cholesterol than those with insurance (Wilper et al., 2009). Most significantly, people who lack health insurance suffer a higher overall mortality rate than those with insurance. After adjusting for age, sex, education, poorer initial health status, and smoking, it was found that lack of insurance alone increased the risk of dying by 40%, accounting for 45,000 deaths per year (Wilper et al., 2009).

Medicaid, the federal and state public insurance plan, has made great strides in improving access to care for many low income people. As a rule, people with Medicaid have a level of access to medical care that is intermediate between those without insurance and those with private insurance, with the disparity in access between Medicaid and private insurance coverage greater among adults than children.

When Maria Buenasuerte became pregnant, her sister told her that she was eligible for Medicaid, which she obtained. She lived near a community health center and made an appointment the same week with a certified nurse midwife at the clinic for her prenatal intake. She had an uncomplicated pregnancy and delivered a healthy baby at term attended by her midwife and obstetrician at the local community hospital.

Concepcion Ortiz lived in a town of 25,000 persons. When she became pregnant, she enrolled in Medicaid. She called each private obstetrician in town but none would take Medicaid patients. The nearest community health center accepting Medicaid was 75 miles away and no one in Concepcion’s family had a car. When she reached her sixth month, she became desperate.

Compared with uninsured people, those with Medicaid are more likely to have a regular source of medical care and are less likely to report delays in receiving care. For children enrolled in Medicaid, these access measures are comparable to the access reported for children with private insurance. Adults with Medicaid, although much less likely than uninsured adults to report delays in seeking care, are still about twice as likely as privately insured adults to report delays (Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, 2015

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree