Abdominoperineal Resection: Open Technique

Curtis J. Wray

Stefanos G. Millas

DEFINITION

The abdominoperineal resection (APR) refers to the operation for surgical treatment of distal rectal cancer. The APR, as originally described by Ernest Miles, involves the en bloc removal of the distal sigmoid colon, rectum, mesorectum, and anal canal. The operation uses both an abdominal and perineal approach.

The APR requires a permanent end colostomy.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

This operation should be performed for those with a biopsyproven diagnosis of malignancy (e.g., rectal or anal cancer, anal melanoma).

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Patients can present with tenesmus, rectal bleeding, rectal pain, and/or obstructive symptoms. Iron deficiency anemia is common at presentation and should always prompt a full colonoscopy in adult patients. Asymptomatic patients are typically diagnosed during screening colonoscopy.

A thorough history should be obtained to assess the patient’s functional status and to ensure sufficient physiologic reserve to undergo a major abdominal operation.

A detailed family history is necessary to identify risk of an inherited colon and rectal cancer syndrome as well as risk for metachronous colorectal cancer.

Digital rectal examination and rigid proctosigmoidoscopy can be performed in the ambulatory office and provide an accurate measurement of tumor distance from anorectal ring when compared to a flexible sigmoidoscopy. It also allows for evaluation of potential tumor fixation to the anal sphincter, pelvic side walls, sacrum, and/or urologic/gynecologic organs.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

A complete colonoscopy is obtained to evaluate for potential synchronous lesions that may have to be addressed at the time of surgery.

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis with intravenous and oral contrast should be obtained to assess for the presence of metastatic disease and the extent of tumor involvement within the pelvis.

A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pelvis with intravenous (IV) contrast, or endorectal ultrasound performed by a qualified endoscopist, should be obtained for local tumor staging that will guide neoadjuvant chemotherapy and radiation as per National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines. Endorectal ultrasound has a higher sensitivity and specificity for tumor depth rather than lymph node involvement as compared to MRI. MRI allows for a better assessment of the circumferential margin at the mesorectal envelope.

Laboratory blood work should include a complete blood count, serum electrolytes, liver function tests, and a carcinoembryonic antigen level as a baseline measurement that will be the reference for future cancer surveillance.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Although controversial, a margin less than 2 cm between the tumor and the anorectal ring will typically require an APR to ensure adequate tumor clearance and a satisfactory functional outcome.

The patient may be placed in the lithotomy position and two surgical teams can work simultaneously. Alternatively, one team can perform both portions of the operation sequentially.

Preoperative Planning

The patient should take a mechanical bowel preparation (GoLYTELY) the day before surgery.

Recent evidence suggests an oral antibiotic preparation reduces postoperative surgical site infections.

The colostomy site should be marked preoperatively with the patient in a sitting and supine position to ensure skin folds and crevices do not interfere with the appliance. Ideally, this marking should be performed by a qualified enterostomal therapist (wound, ostomy, and continence nurse [WOCN]).

The stoma is marked over the (left) rectus abdominus, typically below the level of the umbilicus, though it can be placed above the umbilicus to facilitate a large pannus or high belt line.

Tumor fixation by rectal exam is unreliable in determining whether or not a low rectal tumor is resectable.

Tumor fixation within the pelvis does not necessarily imply infiltration of tumor into surrounding structures.

Inflammatory adhesions within the pelvis does not portend a worse prognosis with respect to local recurrence or overall mortality.

Ultimate decision on whether to proceed with an APR is made at the time of laparotomy.

Positioning

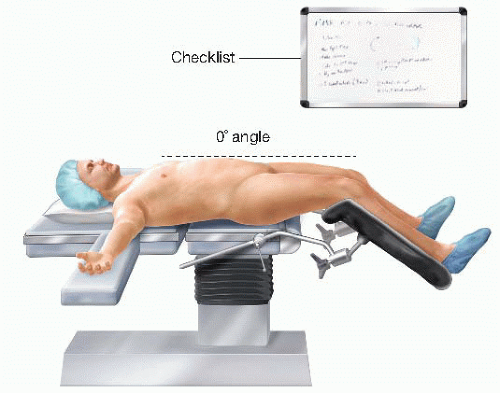

The patient is placed in a modified lithotomy position with Allen stirrups.

The thighs are level with the abdomen as this allows efficient placement of a self-retaining retractor without creating excessive pressure between the retractor and the patient’s thighs (FIG 1).

The perineum is positioned flush with the edge of the operating room table.

FIG 1 • Patient positioning on the operating table. Note the horizontal position of the thighs to ensure free movement of surgeon’s arms and hands. The perineum is flushed to the end of the table.

The pelvis is supported with a folded sheet to lift the entire perineum and facilitate exposure during the perineal dissection.

The arms are placed in a neutral position and supported with suitable armrests.

The anus is closed with a purse-string monofilament suture (0-Prolene with circle taper 1 [CT-1] Ethicon needle, or equivalent).

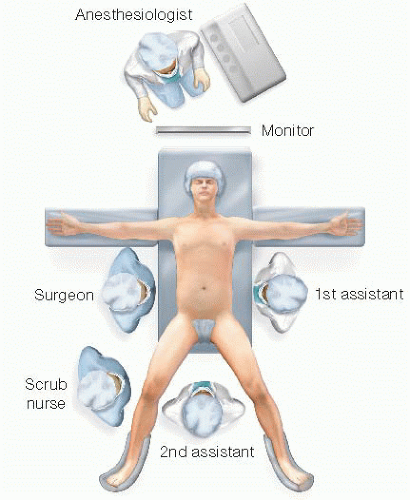

For the abdominal phase of the operation, the surgeon stands by the patient’s right side, with his or her assistant standing at the patient’s left side. A second assistant, if available, stands in between the patient’s legs. The scrub nurse stands at the surgeon’s right side, by the patient’s right leg (FIG 2). The surgeon and the first assistant will switch sides as necessary during the pelvic dissection.

During the perineal phase, the surgeon and the first assistant will be situated in between the patient’s legs, with the second assistant by the patient’s right or left side.

TECHNIQUES

EXPOSURE

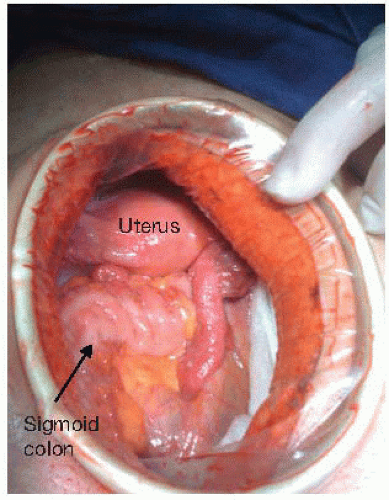

Exposure of the abdomen is obtained with a lower midline incision from the umbilicus to the pubic symphysis. A wound protector may be inserted to protect the wound from infectious and oncologic soilage (FIG 3).

The abdomen should be fully explored for the presence of gross metastatic disease.

Care should be taken to evaluate all peritoneal surfaces, the entire gastrointestinal tract, the omentum, and the liver.

Any concerning lesions away from the primary tumor should be biopsied and evaluated by intraoperative cryosection.

A self-retaining retractor is positioned to optimize exposure of the pelvis.

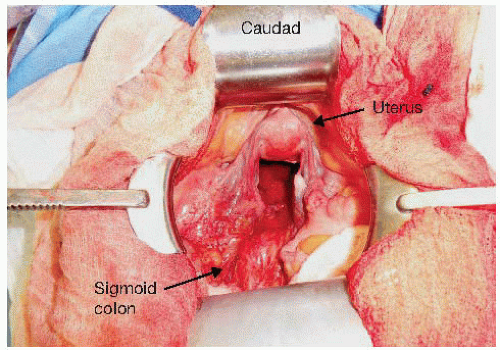

Two short Richardson attachments are used to retract the abdominal wall laterally, in a perpendicular orientation to the incision to avoid undue traction on the femoral nerves at the pelvic inlet (FIG 4).

A bladder blade is positioned at the inferior aspect of the incision to retract the bladder and uterus. A 2-0 silk, figure-of-eight suture through the fundus of the uterus can facilitate positioning the uterus behind the bladder blade.

The small bowel is packed into the upper abdomen; this maneuver is facilitated by not extending the incision beyond what is required to access the origin of the inferior mesenteric artery.

A malleable retractor attachment for the Bookwalter and moistened laparotomy pads aid in keeping the small bowel out of the pelvis.

Mobilization of Sigmoid Colon and Transection of the Inferior Mesenteric Artery

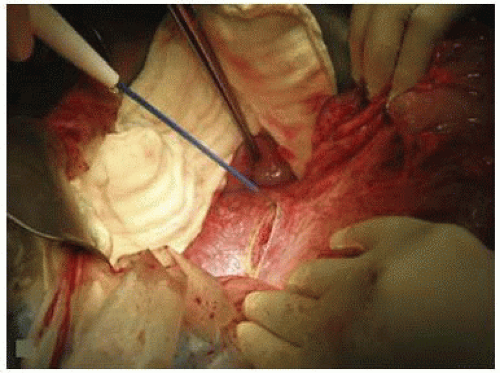

The lateral peritoneal attachments to the sigmoid colon are divided, exposing the plane between the sigmoid mesocolon and the retroperitoneum (FIG 5).

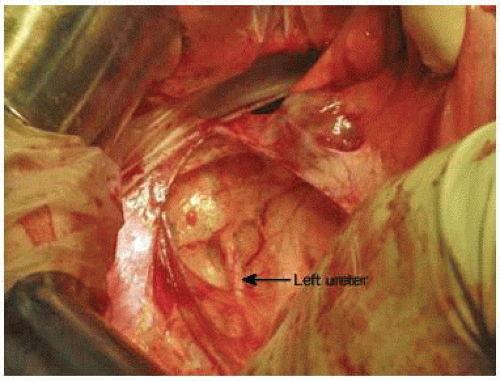

Mobilization of the sigmoid mesocolon allows for exposure and preservation of the left ureter and gonadal vessels, which should always be identified prior to dividing the inferior mesenteric artery at its origin (FIG 6).

FIG 5 • Sigmoid colon mobilization. With the descending colon retracted medially, the lateral peritoneal attachments are transected with electrocautery along the left paracolic gutter.

FIG 6 • Identification of the left ureter. After full mobilization of the descending colon, the left ureter is exposed in the retroperitoneum. The surgeon is retracting the descending colon medially.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access