Abdominoperineal Resection: Laparoscopic Technique

Joël Leroy Didier

Mutter Jacques Marescaux

DEFINITION

An abdominoperineal resection, or APR, involves removal of the anus, the rectum, and part or all of the sigmoid colon along with the associated regional lymph nodes, through incisions made in the abdomen and perineum. The end of the remaining colon is brought out as a colostomy.

The laparoscopic abdominoperineal amputation of the rectum is a totally laparoscopic intervention, as specimen removal is performed through a perineal excision without compromising the oncologic aspect of the surgical procedure.

INDICATIONS

Indications for laparoscopic APR:

Rectal cancer: when unable to obtain a negative distal margin and/or in patients with poor sphincter function or severe comorbidities

Anal cancer: after failure of chemotherapy/radiation therapy or in the palliative setting

Inflammatory bowel disease (i.e., Crohn’s with severe perianal disease)

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Most patients with rectal tumors generally present after an incidental finding during screening colonoscopy or with occult bleeding and anemia.

A thorough history and physical examination should include the following:

Presence of rectal pain and/or tenesmus

Presence of obstructive symptoms

Description of anorectal function, with any fecal incontinence or leakage documented preoperatively

Documentation of urinary and erectile function/dysfunction

A detailed personal and family history of colorectal cancer, polyps, and/or other malignancies

Physical examination should include the following:

Routine abdominal examination, noting any previous incisions

Digital rectal examination with assessment of sphincter function

Bilateral inguinal nodal examination

Rigid proctoscopy is arguably the most critical portion of the physical examination and is the key to proper patient selection of patients for an APR.

Proctoscopy should be standardized and documented at minimum.

The distal and proximal extent of the lesion measured from the anal verge

Exact position of the lesion and extent of the rectal circumference involved

Presence or absence of fixation to perirectal structures

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

A colonoscopy with documentation of all polyps should be performed. Suspicious lesions should be tattooed to facilitate localization during surgery.

Staging with endorectal ultrasound or rectal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) should be performed to determine the need for neoadjuvant therapy and to plan operative strategy. A computed tomography (CT) of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis evaluates for potential metastases.

A preoperative carcinoembryonic antigen level should be obtained.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Preoperative Planning

Informed consent is obtained preoperatively. The patient has been informed of the necessity to perform a definitive colostomy.

The colostomy site is marked by a skin tattoo the evening before the intervention.

We follow the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons’ (SAGES) bowel preparation guidelines.

Appropriate intravenous antibiotics are administered within 1 hour of skin incision.

Equipment and Instrumentation

10-mm, 0-degree camera (30-degree camera is optional) with high-resolution monitors

Laparoscopic endoscopic scissors and a blunt tip, 5-mm energy device (10-mm in obese patients)

Laparoscopic linear staplers

Positioning and Port Placement

Patient setup

Patient setup is a major operative step.

The patient should be adequately secured to the table.

Adequate padding is essential to prevent nerve and venous compressions.

The patient is placed in a supine position with a cushion placed underneath the left flank in order to obtain a moderate lateral decubitus, which will retract bowel loops toward the right part of the abdomen.

A rotation to the right and a caudal head tilt (Trendelenburg position) will help to retract bowel loops by means of gravity.

The patient’s legs will then be spread apart in a semiflexion using adjustable leg supports to allow for a double abdominal and perineal access.

One should control the perfect positioning of the buttocks at the distal edge of the table to allow for an easy access to the anal and perineal area.

FIG 1 • Team setup. Surgeon (1). First assistant (2). Second assistant (3). Scrub nurse (4). Anesthesiologist (5).

The arms are padded and tucked alongside the body.

An orogastric tube is inserted; it will be removed at the completion of the surgery.

A Foley catheter is inserted; it will be left in place for 24 hours.

Team positioning

This procedure is performed with two assistants and a scrub technician.

A table is prepared for the abdominal part of the intervention.

A second table is used for the peritoneal part of the operation.

During the abdominal part of the procedure (FIG 1), the surgeon stands on the right flank of the patient, his or her first assistant lateral to the patient’s right shoulder, and the second assistant in between the patient’s legs. The scrub technician is then located to the right of the surgeon lateral to lower limbs.

During the perineal part of the procedure, the entire team shifts toward the extremity of the table once the perineum has been exposed.

The monitors are placed in front of the operating team and at eye level to improve ergonomics.

Port placement

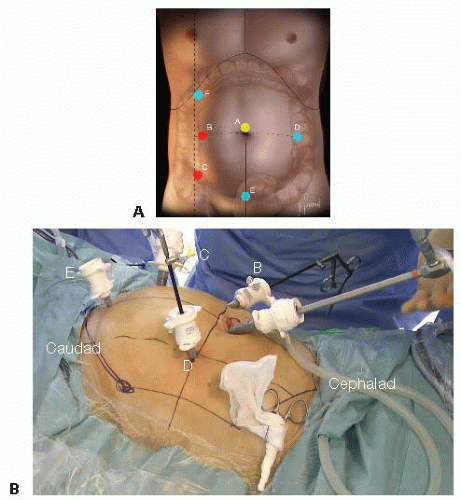

One 12-mm supraumbilical port (port A) is introduced first using a mini-open technique. It will be used to accommodate the camera (FIG 2).

Two other ports, a 5-mm port in the right flank (port B) and a 12-mm port in the right iliac fossa (port C), are used as operating ports (FIG 2).

The fourth port in the left flank at the level of the umbilicus is inserted through the rectus muscle (port D, 5 mm in diameter), where the colostomy will be performed (FIG 2).

The last port introduced in the suprapubic area (port E, 12-mm in diameter) is used for pelvic retraction and for exposure of the sigmoid colon’s root (FIG 2).

Port fixation in the wall should be perfect in order to prevent any risk of parietal injury and to prevent increased operative times due to a loss in abdominal pressure. One should not hesitate to fix ports to the skin.

Additional ports may be used in case of difficulty in exposure. In this case, a port will be positioned in the right hypochondrium (port F) to retract the ileocecal area. This is particularly useful in obese patients.

FIG 2 • Port placement. A. Optical port (A). Working ports (B,C). Retracting ports (D,E). Additional retracting port (F). B. External view from the left side of the patient. |

TECHNIQUES

LAPAROSCOPIC ABDOMINOPERINEAL RESECTION

Exploration and Exposure

The intervention is begun by an exploration of the abdominal cavity to locate the tumor and evaluate for possible metastases. It also allows to expose the pelvis and to evaluate the length and quality of the sigmoid loop, which will allow determining the type of mobilization of the left colon and of the splenic flexure.

The tumor’s identification may be necessary and especially so for tumors located proximally. Combined endoscopy may be required in cases where an effective preoperative marking could not be performed on the day before the intervention.

Exposure is improved by placing the patient in a Trendelenburg position with the table tilted to the right.

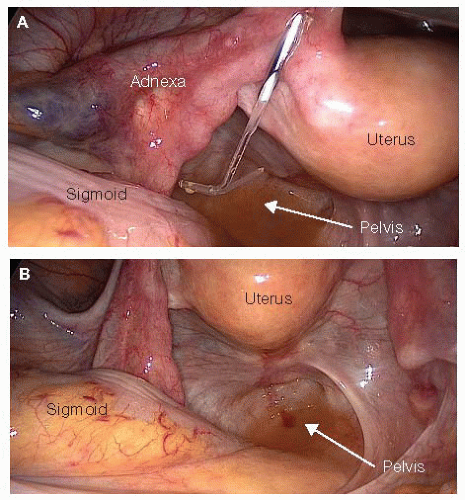

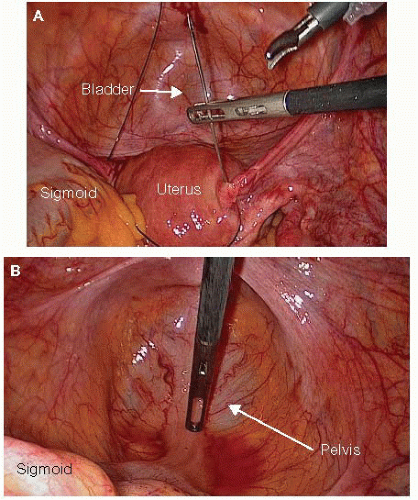

In women, exposure of the posterior pelvis and of the rectovaginal (Douglas’) pouch can be obtained by direct or indirect suspension of the uterus by means of the T’Lift™ (VECTEC, France) tissue retraction device (FIG 3A,B) or suprapubic transparietal sutures (FIG 4A,B).

Visceral obesity (in male patients) is more incapacitating than subcutaneous obesity (in female patients). The use of retractors is very helpful.

Primary Vascular Oncologic Approach to the Sigmoid Colon

As for any oncologic surgical procedure, a primary vascular approach is the rule.

FIG 4 • A. Transparietal suprapubic sutures for uterine suspension. B. Exposure of the pelvis in women after transparietal suprapubic suture uterine suspension.

In rectosigmoid cancer, one should approach the inferior mesenteric vessels at their origin in order to perform an “en bloc” removal of all lymph nodes associated with the rectosigmoid junction (D3 resection). It does not prevent the potential preservation of the proximal inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) and of the left colic artery (LCA).

We always start with a primary approach to the IMA. The inferior mesenteric vein (IMV) is then approached in order to prevent any venous overload related to the late ligation of the IMA.

Once the root of the sigmoid mesocolon has been exposed, the left retroperitoneal space is opened by incising the posterior peritoneum from the anterior aspect of the promontory up to the left border of the duodenojejunal junction (ligament of Treitz) (FIG 5A).

Once the retroperitoneum has been opened, dissection is initiated opposite the promontory on the posterior aspect of the inferior mesenteric vascular sheath (i.e., the superior rectal artery at this level). This step is facilitated by the anterior traction on the mesocolon, which induces the pneumodissection of the retrovascular space, thanks to intraabdominal carbon dioxide pressure.

Dissection is carried on in contact with the vascular sheath cranially until the origin of the IMA on the aorta.

The dissection is continued from caudad to cephalad in contact with the artery, which is skeletonized over approximately 2 cm in order to achieve ligation and division 1 or 2 cm away from the aorta (FIG 5B).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree