Introduction

As a healthcare or physician leader, no resource is more vital to your department—or, indeed, your organization as a whole—than your human capital. In today’s competitive career marketplace, utilizing strong recruitment techniques goes hand in hand with understanding the latest legal policies and labor practices. The process of selecting quality employees requires managers to go through six distinct phases before hiring. Orientation, training, and performance appraising are all activities managers engage in to develop strong employees. Turnover and termination compel managers to continually engage in the hiring and training process. Managers who respond appropriately to office conflict and politics shape a more productive workplace for themselves and their staff members.

Meeting Today’s Human Resource Demands

People, in all of their diversity, are essential in healthcare organizations. No one’s talents can be wasted in the quest for high performance or greater efficiency. In principle, at least, the following slogans say much about the importance of the human beings that make up today’s organizations:

People are our most important asset.

It’s people who make the difference.

It’s the people who work for us who determine whether our healthcare organization thrives or languishes.

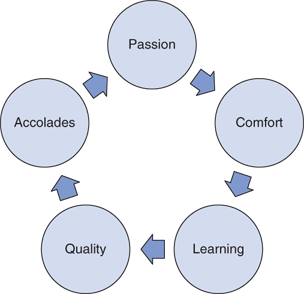

The basic building blocks of any high-performance healthcare organization are talented workers with relevant skills and great enthusiasm for their work. One manager summed up the situation as such: “If you hire the right people … if you’ve got the right fit … then everything will take care of itself.” As depicted in Figure 3–1, ensuring that you are doing all that you can to make all of your staff members meet their top potential by playing to their strengths is the starting point for maximizing staff performance.

Human Resource Management

Human resource management (HRM) involves attracting, developing, and maintaining a talented and energetic workforce to support organizational mission, objectives, and strategies. In order for strategies to be well implemented, workers with relevant skills and enthusiasm are needed. The task of human resource management is to make workers available.

Attracting a quality workforce involves human resource planning, recruitment, and selection.

Developing a quality workforce involves employee orientation, training and development, and career planning and development.

Maintaining a quality workforce involves management of employee retention and turnover, performance appraisal, and compensation and benefits.

Additionally, human resource management must be accomplished within the framework of government regulations and laws. All managers are expected to act within the law and follow equal opportunity principles. Failure to do so is not only unjustified in a free society, but it can also be a very expensive mistake resulting in fines and penalties.

The American legal and regulatory environment covers human resource management activities related to discrimination, pay, employment rights, occupational health and safety, retirement, privacy, vocational rehabilitation, and related areas. It is also constantly changing as old laws are modified and new ones are added.

A Primer on the Law and Leadership

Legal issues in human resource management are continually before the courts. The more prominent among them are frequently in the news. Committed healthcare managers and human resource professionals need to stay informed on the following issues of legal and ethical consequence. There are a myriad of important issues that impact the healthcare work environment every day. In this section, a basic overview is provided to help parse fact from fiction with the proviso that anytime is a good time to get an assist from your human resource department when confronted (if not confounded) by a potentially legal situation with a staff member.

Employment discrimination is when someone is denied a job or a job assignment for reasons that are not job relevant. It is against federal law in the United States to discriminate in employment.

An important cornerstone of legal protection for employee rights to fair treatment is found in Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended by the Equal Employment Opportunity Act (EEOA) of 1972 and the Civil Rights Act of 1991. A working synopsis of important legislative stricture includes

Equal employment opportunity (EEO): The right to employment without regard to race, color, national origin, religion, gender, age, or physical and mental ability. The intent is to ensure all citizens have a right to gain and keep employment based only on their ability to do the job and their performance once on the job.

EEO is federally enforced by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), which has the power to file civil lawsuits against organizations that do not provide timely resolution of any discrimination charges lodged against them. These laws generally apply to all public and private organizations employing 15 or more people.

Under Title VII, organizations are also expected to show affirmative action.

Affirmative action gives preference in hiring and promotion to women and minorities, including veterans, the aged, and the disabled. Affirmative action ensures that women and minorities are represented in the workforce in proportion to their actual availability in their respective labor market area.

Affirmative action plans may also be adopted by or required of organizations to show that they are correcting previous patterns of discriminatory activity and/or are actively preventing its future occurrence.

The pros and cons of affirmative action are debated at both the federal and state levels, and controversies often make the news. Criticisms tend to focus on the use of group membership (eg, female or minority) instead of individual performance in employment decisions. The issues raised include the potential for members of majority populations to claim discrimination. White males, for example, may claim that preferential treatment given to minorities in a particular situation interferes with their individual rights as a claim of reverse discrimination.

As a general rule, EEO legal protections do not restrict an employer’s right to establish bona fide occupational qualification (BFOQ).

Bona fide occupational qualification: Criteria for employment that can be clearly justified as being related to a person’s capacity to perform a job.

The use of bona fide occupational qualifications based on race and color is not allowed under any circumstances; those based on sex, religion, and age are very difficult to support. Years ago, for example, airlines tried to use customer preferences to justify the hiring of only female flight attendants. It didn’t work; today men and women serve in this capacity.

In addition to race and gender, which get a lot of attention in the news, other areas of legal protection against discrimination also deserve a manager’s concern. Listed below are four examples and brief summaries of their supporting laws. The complexities of these laws would require further research into the context of any possible case to which the laws may be applied.

Disabilities: The Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 prevents discrimination against people with disabilities. The law forces employers to focus on abilities and what a person can do. Increasingly, persons with disabilities are gaining employment opportunities.

Age: The Age Discrimination in Employment Act of 1967 (amended in 1978 and 1986) protects workers against mandatory retirement ages. Age discrimination occurs when a qualified individual is adversely affected by a job action that replaces him or her with a younger worker.

Pregnancy: The Pregnancy Discrimination Act of 1978 protects female workers from discrimination because of pregnancy. A pregnant employee is protected against termination or adverse job action because of the pregnancy and is entitled to reasonable time off work.

Family matters: The Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993 protects workers who take unpaid leaves for family matters from losing their jobs or employment status. Workers are allowed up to 12 weeks’ leave for childbirth, adoption, personal illness, or illness of a family member.

Sexual harassment: Sexual harassment occurs when a person experiences conduct or language of a sexual nature that affects his or her employment situation. According to the EEOC, sexual harassment is behavior that creates a hostile work environment, interferes with their ability to do a job, or interferes with their promotion potential.

Equal pay: The Equal Pay Act of 1963 provides that men and women in the same organization should be paid equally for doing equal work in terms of required skills, responsibilities, and working conditions. However, a lingering issue involving gender disparities in pay involves comparable worth, the notion that persons performing jobs of similar importance should be paid at comparable levels. Why should a long-distance truck driver, for example, be paid more than an elementary teacher in a public school? Does it make any difference that the former is a traditionally male occupation and the latter a traditionally female occupation? Advocates of comparable worth argue that such historical disparities are due to gender bias. They would like to have the issue legally resolved.

Part-time and temporary workers: The legal status and employee entitlements of part-time workers and independent contractors are also being debated. In today’s era of downsizing, outsourcing, and projects, more and more people in all industries—including health care—are being hired as temporary workers who work under contract to an organization and do not become part of its official workforce. They work only as needed. Problems occur when these individuals are engaged regularly by the same organization and become what many now call perma-temps. Even though regularly employed by one organization, they work without benefits such as health insurance and pension eligibilities. If they were legally considered employees, these independent contractors would be eligible for benefits, and the implications for their employers would be costly. A number of legal cases are now before the courts seeking resolution of this issue.

Labor-management relations: Union representation for healthcare workers is becoming increasingly common, particularly in larger cities where sizable groups of professionals with similar skills and employment opportunities exist. Nurses of various levels, laboratory technicians, and even office managers can belong to unions. Healthcare labor unions are frequently involved in contract negotiations and unfair employment practices investigations. Labor-management issues and their legal foundations are discussed later in the chapter.

Labor-Management Relations

Another aspect of human resource management relates to the influence of organized labor. Labor unions are organizations to which workers belong that deal with employers on the workers’ behalf. Labor unions act as bargaining agents, negotiating legal contracts that affect many aspects of human resource management. Labor contracts typically include the rights and obligations of employees and management with respect to wages, work hours, work rules, seniority, hiring, grievances, and other aspects of employment. The foundation of any labor and management relationship is collective bargaining, which is the process of negotiating, administering, and interpreting labor contracts. Labor contracts and the collective bargaining process are governed closely in the United States by a strict legal framework.

The Wagner Act of 1935 protects employees by recognizing their rights to join unions and engage in union activities.

The Taft-Hartley Act of 1947 protects employers from unfair labor practices by unions and allows workers to decertify unions.

The Civil Service Reform Act Title VII of 1978 clarifies the rights of government employees to join and be represented by labor unions.

Often, labor and management are viewed as win-lose adversaries, destined to be in opposition and possessed of certain weapons with which to fight one another. If labor-management relations take this form, a lot of energy on both sides can be expended in a prolonged conflict.

Some believe that this model is, to some extent, giving way to a new and more progressive era of greater cooperation. Fortunately, because most healthcare organizations are nonunion, and the majority of states are right to work which means that unions do not control the selection and hiring process, this factor will likely not be prominent in your leadership equation.

Human Resource Professionals—Know Your Support System

Any healthcare organization should at all times have the right people available to do the requisite management support work. Most healthcare human resource departments will provide support in five critical areas.

Establish organization standards for new employee selection at both the staff and managerial levels that can be used in both external (new employee) and internal (existing employee) selection.

Implement recruitment systems that maximize all potential and possible sources for new talent acquisition for all clinical, nonskilled and professional positions.

Lead targeted searches for high-level positions, as designated by the CEO and COO, to include executive positions and high-demand/low-supply skilled specialist positions.

Consult as needed and as requested by line managers and directors on the identification of sources for potential candidates for critical positions, and provide specific counsel on the successful recruitment and selection of high-potential new organizational members.

Lead the processes and programs of new employee orientation to include aiding line managers in specific individual development plan.

Designate appropriate compensation and benefit packages for incorporation into offer letters and contracts for specified new organizational talent at the exempt compensation level.

Ensure that all wage levels throughout the organization are competitive in comparison to similar regional organizations and reflective of the job content and professional requisites of the job position.

Lead effective job analysis and job composition systems to enable efficient performance evaluation, daily management and direction, and clarity of purpose for all employees.

Maintain job equity standards in all positions across the span of the organization by utilizing appropriate and accurate compensation data, conducting wage and position comparative surveys and other strategies.

Monitor benefit and compensation programs and packages beyond salary and pay in order to maintain fairness, optimize available payroll and labor budgeted costs, and heighten employee morale and good employee retention.

Fuse advantageously not only base pay but also cost of living increases, bonuses, incentive pay, and other yearly incentives into tactically insightful performance improvement and quality enhancement programs at the individual, departmental, and organizational levels.

Work in concert with the director of organizational development to implement needed education, training and development on key technical, industry and organizational subjects through traditional in-service, and other delivery modalities.

Lead comprehensive and targeted efforts in conjunction with line managers to maintain progressive and positive quality of work life across the panoply of the organization.

Conduct town hall meetings and other forums that encourage maximum participation by employees to provide input, suggestions, and solution formulation to any and all issues significant to daily work life.

Act as a moderator for performance improvement discussions when appropriate, and lead initiatives that can help improved communication and action response to significant employee issues at all levels, to include affiliates such as major physician practices and other constituencies in the organization.

Manage proactively any programs and systems that help maintain the organization’s nonunion status and position as an employer of choice in its competitive regional area.

Assist in the placement, orientation, education, and development of volunteers who while not paid employees must demonstrate the guest relations skills and reflect the professional standards of the organization.

React immediately and reliably to all requests from managers at all levels of the organization for consultation on performance problems specific to unsatisfactory individual employees and lackluster work groups.

Lead and manage a staff of human resource and personnel administrative professionals at both the hourly/staff and exempt/professional levels, as provided and designated by executive leadership in the daily administration of continuous human resource and personnel administration and in response to change/crisis dynamics impacting the organization’s human capital.

Maintain a state-of-the-art IT system that supports all human resource management and personnel administration processes and procedures to include job description, performance evaluation, and compensation data.

Compose a dynamic human resource and personnel administration strategic plan for the entire organization by identifying pertinent external dynamics, organizational needs, and growth imperatives relative to the organization’s current and emergently needed human capital.

Implement needed equal employment opportunity, affirmative action and other legally mandated protections, programs and processes comprehensively throughout the organization through education, enforcement, and expedient execution of action as needed.

Resolve manager-employee conflicts as requested by executive administration or the parties intrinsic to the situation(s) through immediate response, fact finding and direct counseling, and when necessary, with the engagement of legal or other expertise.

Ensure compliance and constructive response to all relevant national and local existing labor statutes, as well as new mandates that directly impact the organization’s workforce and leadership.

Coordinate and lead all community outreach and local liaison efforts, such as job fairs, educational institution events, and other opportunities to enhance the organization’s presence relative to the local and regional communities.

Contract with needed consultants and other experts economically and pragmatically as needed to continually maximize human resource strength.

Planning Considerations for Your Staff

Strategic human resource planning: A process of analyzing staffing needs and planning how to satisfy these needs in a way that best serves the organizational mission, objectives, and strategies. The foundations for human resource planning are set by job analysis conducted by human resource professionals with significant input from managers at various levels.

Job analysis: The orderly study of just what is done, when, where, how, why, and by whom in existing or potential new jobs. Job analysis—which often includes human resource personnel observing and interviewing employees who do a specific job and then collaborating with managers to write a comprehensive description of all that a job entails—provides useful information that can then be used to write and/or update job descriptions and job specifications, which can then be shared with employees and potential job applicants.

Job descriptions: Written statements of job duties and responsibilities.

Job specifications: Lists of the qualifications—such as formal education, prior work experience, and skill requirements—that should be met by any person hired for or placed in a given job.

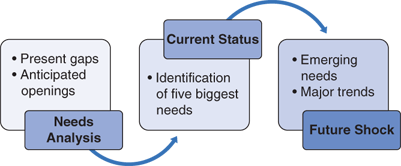

The elements in strategic human resource planning are shown in Figure 3–2. The five-step process outlined in the figure begins with a review of organizational mission, objectives, and strategies, which establishes a frame of reference for forecasting human resource needs.

Ultimately, the planning process helps managers identify staffing requirements, assess the existing workforce, and determine what additions or replacements are required to meet future needs. The entire process, of course, must be implemented in a manner consistent with the legal environment.

Attracting a Quality Workforce

Attracting and selecting new members of your team can easily spell the difference between success and failure as a healthcare manager. When you select a top performer, you have an individual from whom the entire team can draw inspiration and rely on for steady or stellar performance. Conversely, when you select an individual who is not a top performer, the negative results can be staggering.

Although far from being an exact science, the process of hiring and selecting new employees can take on some structure, complete with strategies and proven approaches for success. After a human resource plan is prepared, the process of attracting a quality workforce can systematically begin.

Recruitment is a set of activities designed to attract a qualified pool of job applicants to an organization. Emphasis on the word qualified is important.

Effective recruiting should bring employment opportunities to the attention of people whose abilities and skills meet job specifications. The three basic steps in a typical recruitment process are

Advertise a job vacancy.

Establish preliminary contact with potential job candidates.

Perform an initial screening to identify all qualified applicants.

In recruiting potential nursing candidates soon to graduate from a healthcare training school, for example, advertising is done by a hiring hospital by posting short job descriptions in print or on Web sites through the campus placement center. Preliminary contact is made after candidates register for interviews with hospital recruiters on campus. Preliminary interviews typically run 20 to 30 minutes, during which the candidate presents a written resume and briefly explains his or her job qualifications. To further screen the candidates, the hospital recruiter shares interview results and resumes with key decision makers at the hospital. They choose a final pool of candidates to be invited for further interviews during a formal visit to the organization.

Recruitment is certainly one of the most difficult endeavors for the modern-day healthcare manager. The reason for this is the ongoing shortage of qualified personnel in virtually all healthcare positions. This means you must work assiduously toward generating a good roster of candidates and use as many recruitment sources as possible.

Recruitment can be either internal or external:

External recruitment, in which job candidates are sought from outside the hiring organization. Newspapers, employment agencies, colleges, technical training centers, personal contacts, walk-ins, employee referrals, and even competing healthcare organizations are all sources of external recruits.

Internal recruitment seeks applicants from inside the organization. This involves notifying existing employees of job vacancies. Most healthcare organizations have a procedure for announcing vacancies through newsletters, electronic bulletin boards, and the like. They also rely on managers to recommend high-performing workers as candidates for advancement.

Both recruitment strategies offer potential advantages. External recruiting brings in outsiders with fresh perspectives and provides access to specialized expertise or work experience not otherwise available from insiders. Internal recruitment is usually less expensive and involves people whose performance records are well established. A history of serious internal recruitment can also be encouraging to employees; it shows that one can advance in the organization by working hard and achieving high performance at each point of responsibility.

Healthcare managers rely on several tried-and-true methods to recruit quality job candidates. Although organizations have specific techniques and resources (consult with your human resource department), the following tactics are all useful:

Job fairs: Whenever possible, try to attend job fairs in your specific technical area. Although many job fair attendees are simply shopping around and aren’t interested in immediate employment, collecting resumes and obtaining information on potential candidates is a continuous process for proactive healthcare managers.

School liaisons: Many healthcare professionals maintain contact with the schools they graduated from. Contact the school’s placement office or a favorite teacher, and ask whether any up-and-coming talent may be suitable for your open position. School liaisons may also know alumni in the field who may be suitable candidates as well. If you are trying to fill an entry-level position, contact a guidance counselor at a local high school or vocational school and inquire about likely candidates.

Employment referral systems: Most organizations have an employee referral system in which employees refer qualified individuals to human resource for openings in the organization. If your organization does not have an employee referral system or if you work in a small healthcare organization, discuss with your supervisor the possibility of providing a monetary reward to an employee who recommends a candidate for an open position who is subsequently hired.

Professional contacts: Contact former colleagues or institutions and discuss the availability of potential candidates. If you belong to a professional organization, contact a representative within that organization to generate a list of potential candidates.

Agencies: Many healthcare recruiters frown on placement and search agencies because recruitment services are costly and often yield less than satisfactory results. Contact an agency only with the assistance of your human resource department or your immediate supervisor. When you work with an agency, spend as much time as possible with the primary recruiter in developing a list of expectations and revised job descriptions.

Advertising: Employment advertisements in print and online media can be somewhat expensive, and unfortunately they can provide inconsistent results. If you run an advertisement, work with your human resource director and supervisor to craft the advertisement. Make certain the advertisement receives good placement within the newspaper or magazine, has a catchy logo, and contains a three-to five-sentence depiction of the job, the salary range, and the name of a specific contact person. These elements will eliminate people who are simply job shopping or who are not in the salary range established for the position.

Team/staff referrals: Members on your own team may know someone qualified for an open position. However, unless they are asked, your team members may assume you’re not interested in their recommendations.

Smaller healthcare providers, particularly in rural areas or in distinct neighborhoods (eg, those of large East Coast cities), use community-based recruitment. These institutions write a three-to five-sentence depiction of the open position, the point of contact, and salary range, and make copies on their organization’s stationery. They post these copies on bulletin boards in key areas within the community: supermarkets, convenience stores, libraries, community centers, post offices, and places of worship.

When using community-based recruitment, be sure to get permission from the appropriate authority at each posting area. Getting their permission is also an opportunity for you to gain their support and participation in the search effort by reviewing the contents of your notice and discussing any potential applicants they might know among their customers or congregation. The business and religious anchors in the community are typically positive allies in the healthcare recruitment process.

To avoid the negative aspects of hiring a poor performer, you need to understand the selection process. Selection is the process of choosing from a pool of applicants the person or persons who offer the greatest performance potential. Healthcare managers who successfully master the selection process not only diminish the chance that they have to terminate poor performers or address performance problems, but they also enhance all their management responsibilities by having the luxury of working with well-motivated, talented people.

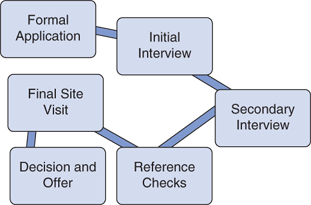

Figure 3–3 shows the typical steps in the selection process, and the following section explores each step of the selection process in greater detail.

Applicants typically use two important documents to apply for jobs:

The application form declares an individual to be a formal candidate for a job. It documents the applicant’s personal history and qualifications. The application should only request information that is directly relevant to the job and the applicant’s potential job success.

The personal resume is often included with the job application and should accurately summarize an applicant’s special qualifications. As a recruiter and hiring manager, you need to learn how to screen applications and resumes for insights that can help you make good selection decisions.

Your main objective in reviewing resumes is to determine whether the person can do the job. (The interview is where you determine what type of person the candidate is and how they would do the job.) Try to sort the resumes by your criteria, and organize the candidates into three basic categories: unqualified, possible, and probable candidates.

Unqualified applicants simply do not have the quantitative skills established on the job description. For example, they do not have either the required degree or years of experience required.

Possible candidates have the quantitative skills sought and may have additional factors that merit consideration. For example, for the position of staff pharmacist, an individual in the possible category may have all the necessary degrees, including the specific professional accreditation to prepare for state compliance reviews, and a good range of years of professional experience.

Probable candidates are individuals who seem almost perfect for the position. This is typically the smallest group of applicants.

Establish a short list of candidates, beginning with the probable group and including applicants from the possible group until you have approximately seven or fewer candidates. However, do not fall into the seductive trap of reading too much into a resume. Try to take the information at face value; remember that the resume is simply a summary of qualifications, not an in-depth insight into the applicant’s personality.

Interviews are extremely important in the selection process because of the information exchange they allow. Thus, a comprehensive interview guide is the resource for this chapter, and this section is provided. The interview is a time when both the job applicant and potential employer can learn a lot about one another. However, interviews are also recognized as potential stumbling blocks in the selection process. To avoid them, keep these general pointers in mind when you conduct a job interview:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree