Acute Porphyrias

Disease summary:

All porphyrias are diseases resulting from abnormalities of heme biosynthesis.

The four acute porphyrias, in descending order of prevalence, and their inborn enzymatic errors are intermittent acute porphyria (IAP; ∼50% reduction in porphobilinogen deaminase), variegate porphyria (VP; ∼50% reduction in protoporphyrinogen oxidase), hereditary coproporphyria (HCP; ∼50% reduction in coproporphyrinogen oxidase), and delta-aminolevulinic acid (ALA) dehydratase deficiency porphyria (ADP; >95% reduction in ALA dehydratase).

IAP, VP, and HCP are inherited as autosomal dominant syndromes; ADP is an autosomal recessive syndrome.

Carriers of the gene for IAP, VP, and HCP may have no manifestations or chronic but low-level manifestations (the majority), or acute attacks that may be life threatening.

Homozygotes for the gene causing ADP may be symptomatic frequently, commencing often in childhood. Heterozygotes may be liable for developing lead toxicity.

Precipitants of the acute attack are intercurrent illness, certain medications, environmental agents (eg, impurities in drinking water, organic solvents), dietary restriction, or hormonal fluctuations in the menstrual cycle. Often the cause is unknown.

Hereditary basis

IAP, HCP, and VP—autosomal dominant, with low penetrance resulting from variable environmental stimuli. ADP—autosomal recessive; apparently exceedingly rare. Penetrance may approach 100%.

Differential diagnosis (Table 89-1)

Manifestations are often nonspecific, and misdiagnosis is common.

Abdominal pain consistent with the pain of an acute porphyria is common in constipation, acute gastroenteritis, functional bowel disease, celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease, pseudomembranous colitis (Clostridium difficile toxin), gall bladder disease, pancreatitis, etc.

The sympathomimetic manifestations resemble those in pheochromocytoma, thyrotoxicosis, delirium tremens, and neuroleptic malignant syndrome.

Ascending polyneuropathy is seen in Guillain-Barré syndrome.

The cutaneous manifestations of HCP and VP resemble those of porphyria cutanea tarda (PCT).

The possibility that an acute porphyria is responsible for the manifestations of an acute event can be resolved definitively by finding highly abnormal quantities of porphyrin precursors porphobilinogen (PBG) and/or ALA in a spot urine obtained during this attack. Marked elevations of PBG and/or ALA are the rule during an acute attack. Normal urinary PBG and/or ALA excretion rules out an acute porphyric attack.

| Syndrome | Gene Symbol | Associated Findingsa |

|---|---|---|

| Intermittent acute porphyria (IAP) | PBGD | Pain, hypertension, tachycardia, ascending polyneuropathy, hyponatremia, delirium. Urine ALA, PBG usually ↑↑ |

| Hereditary coproporphyria (HCP) | CPO | As in IAP, also occasional cutaneous blistering. Urine ALA, PBG ↑↑ during attack, often negative otherwise |

| Variegate porphyria (VP) | PPO | Same as HCP |

| ALA dehydratase deficiency porphyria (ADP) | ALAD | Similar to IAP, but manifestations more severe; tends to occur in young people. Urine ALA ↑↑, PBG normal |

| Lead toxicity | – | Similar to IAP. Urine ALA may be ↑, PBG normal. Elevated blood Pb concentration; decreased ALA dehydratase, reversed with Zn, SH-reducing agents |

| Tyrosinemia | FAH | Infantile severe hepatocellular dysfunction, cirrhosis, renal dysfunction, neurologic crises; urine ALA ↑↑, PBG normal. Blood screening (eg, newborn): elevated tyrosine, succinylacetone |

A relative with proven acute porphyria

Intolerances to certain medications, such as oral contraceptives

Episodic burgundy-colored urine that is not hematuria

Episodes of abdominal or other pain of uncertain etiology, including premenstrual abdominal pain

Episodes of ascending peripheral neuropathy

Seasonal blistering of the skin in sun-exposed areas

Chronic manifestations

Intermittent, recurrent body pain, usually in the abdomen or low back

Blistering and fragility of the skin of sun-exposed areas in some patients with VP, HCP

Acute manifestations (acute attacks)

Significant pain, usually but not exclusively abdominal or low back Nausea, vomiting, obstipation, ileus

Hypertension, tachycardia (sympathetic hyperactivity); orthostatic hypotension

Hyponatremia (usually syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion [SIADH])

Varied psychiatric manifestations, including delirium, psychosis Seizures

Loss of deep tendon reflexes, precursor to ascending polyneuropathy (especially motor) leading to quadriplegia and respiratory paralysis

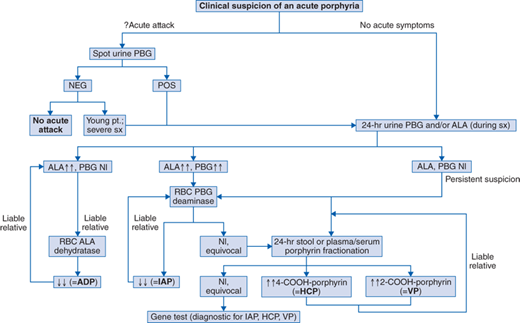

See Fig. 89-1. During a potential acute attack in a patient with an unknown diagnosis—test a spot urine for PBG (PBG Test Kit, Fisher Thermo Scientific, 800-766-7000; available in some hospital laboratories). If positive, or if the patient is a child, follow with a quantitative analysis of a 24-hour urine for both PBG and ALA. For IAP, HCP, and VP, the acute attack is virtually always associated with daily excretion of greater than 20 mg, (increased ∼4×), and usually greater than 50 mg (increased ∼10×), of PBG, ALA. For ADP, ALA is similarly increased; PBG is not increased.

During a potential acute attack in a patient with a known acute porphyria: quantitative analysis of a 24-hour urine for PBG and/or ALA, for comparison with similar data when the patient was previously asymptomatic. Their excretion increases greater than or equal to twofold if elevated at baseline (IAP, ADP) or greater than or equal to fourfold if normal at baseline (VP, HCP).

To evaluate a patient with nonacute symptoms and no diagnosis 24-hour urine (best collected when patient has symptoms) PBG and/or ALA (>20 mg/d usually for IAP; similar elevation in ALA only in ADP; potentially ∼normal for VP, HCP); 24-hour stool or plasma fractionation for specific porphyrins (marked elevations at all time of 4-carboxyl porphyrin [coproporphyrin] in HCP, and of 2-carboxyl porphyrin [protoporphyrin] in VP).

To screen members of a family in which an individual(s) has already been found to have a porphyria: use the studies that were diagnostic in the index case.

IAP—Erythrocyte porphobilinogen deaminase (hydroxymethylbilane synthase) assay. A few patients have normal activity of the erythrocyte enzyme, but a reduction in activity of the visceral (eg, hepatic) enzyme

ADP—Erythrocyte ALA dehydratase assay

HCP, VP—Quantitative stool (preferable) or plasma porphyrin fractionation

Reference Laboratories—Porphyria Laboratory, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX; Tel 409-772-4661

Commercial laboratory—ARUP, Mayo, Quest

IAP, HCP, and VP are autosomal dominant diseases, with a 50% risk for inheriting the gene from an affected parent. Individuals with the gene rarely experience manifestations until after puberty. Penetrance varies with exposure to environmental stimuli, but is in the 10% to 30% range. There is no genotype-phenotype correlation.

ADP is an autosomal recessive, with a 25% risk to each offspring of heterozygous carrier parents. The likelihood of parental consanguinity may be increased. Affected individuals may be ascertained in childhood or early adulthood. Penetrance is not established, but it may approach 100%. A genotype-phenotype correlation may exist. Heterozygotes may be at increased risk for manifestations of lead toxicity.

Emphasis in counseling must include medications or drugs that may precipitate manifestations (databases of safe and unsafe drugs are available on line—eg, www.apfdrugdatabase.com), and possible exacerbating effects of incurrent illness or fasting. All care providers must be aware of the diagnosis, of the potential implications of certain medications, and of the need to deal expeditiously with individuals in whom an acute attack is identified. The risk for hepatocellular carcinoma may be increased.

Patients must

Be educated concerning the causes and effects of the porphyria.

Avoid care providers who fail to become familiar with their porphyrias.

Have a low threshold for consulting their care providers if an acute porphyric attack may be developing, or if they have an intercurrent illness that may precipitate manifestations. Exacerbations may also vary with phase of the menstrual cycle.

Avoid severe dietary restriction, smoking, more than the occasional intake of an alcoholic beverage, or prolonged exposure to organic chemicals such as solvents.

Wear a MedicAlert bracelet or pendant.

Care providers must

Be well informed about causes, effects, and treatments of porphyria.

Patients and their care providers must

Exercise informed judgment regarding the use of drugs or medications; regularly consult an online porphyria drug database—for example, www.apfdrugdatabase.com.

Join the American Porphyria Foundation (www.porphyriafoundation.com) to remain current on new treatments and other developments.

Remove the patient from the source of problems, if possible—for example, hospitalize. Discontinue potentially offending medications.

For individuals with early manifestations of an acute attack (eg, new pain): pharmacologic intake of carbohydrate—daily intake of greater than or equal to 300 g/d of carbohydrate in any form (PO, IV) to abort the attack. Oral Polycose (Polycose Glucose Polymers; Ross, Division of Abbott Laboratories) provides carbohydrate efficiently. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs may be used to prevent premenstrual attacks.

Second line, for individuals with an advanced attack (changes in mental status, seizures, loss of peripheral deep tendon reflexes, ascending paralysis, sympathetic hyper-reactivity, and hyponatremia): hospitalize immediately. Carbohydrate, as above; intravenous heme arginate or hematin (Panhematin, Recordati Rare Diseases, 100 Corporate Drive, Lebanon, NJ 08833), 3 to 4 mg/kg/d, for 4 to 6 days, following clinical manifestations (including deep tendon reflexes, test of respiratory function) and daily urinary excretion of ALA and PBG; free water restriction (for SIADH); beta-blockers in modest dose (for sympathetic hyperactivity).

See Table 89-2.

ADP/ALA dehydratase/9q34

IAP/PBG deaminase/11q23-q24.2

HCP/coproporphyrinogen oxidase/3q11.2-q12

VP/protoporphyrinogen oxidase/1q21-q25

Heme Pathway | |||

| Substrate/Product | Enzyme | Gene | Porphyria Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glycine + Succinate | ALA synthetase | ALAS1, ALAS2 | |

| ALA | ALA dehydratase | ALAD | ADP |

| PBG | PBG deaminase | PBGD | IAP |

| [Hydroxymethylbilane] | Uroporphyrinogen III synthase | UROS | |

| 8-COOH porphyrinogen * (uroporphyrinogen) | Uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase | UROD | |

| 4-COOH porphyrinogen * (coproporphyrinogen) | Coproporphyrinogen oxidase† | CPO | CP |

| 2-COOH porphyrinogen * (protoporphyrinogen) | Protoporphyrinogen oxidase† | PPO | VP |

| 2-COOH porphyrin * (protoporphyrin IX) | Ferrochelatase† | FECH | |

| Heme | |||

Clinical manifestations result from increased demand for heme, for example, for metabolism of a drug. Normally, this demand induces synthesis of ALA synthase, the rate-limiting enzyme, leading to increased heme production. With any of the acute porphyrias, symptoms may result from toxicity of excess product (? ALA) and/or deficiency of heme. In IAP, PBG deaminase (reduced ∼50%) becomes rate limiting, leading to accumulation of ALA and PBG and potential heme deficiency. In HCP and VP, the enzymes that are approximately 50% deficient are not rate limiting; the accumulation of ALA and PBG or the production of heme deficiency may result from porphyrin-mediated inhibition of PBGD. Excess porphyrins act as photosensitizers, causing the cutaneous manifestations in some individuals with CP and VP.