Key Points

Disease summary:

HIV is a blood-borne, sexually transmissible virus that causes immunodeficiency by infecting CD4+ helper T cells. The infection causes an inversion of the normal CD4/CD8 T-cell ratio, dysregulation of B-cell antibody production, and enhances susceptibility to opportunistic infections at advanced disease stages.

HIV is a lentivirus, part of the Retroviridae family, which is an enveloped, positive-sense RNA virus that replicates with a DNA intermediate called a provirus. The provirus integrates into the host-cell DNA and persists for the lifetime of the cell.

The disease is marked by three phases—acute HIV seroconversion, asymptomatic chronic HIV infection, and acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). Depending on the host genetics, the duration of each phase can vary. Acute seroconversion is marked by nonspecific symptoms including fever, flu-like illness, lymphadenopathy, and rash which may occur in half of all people infected with HIV. The asymptomatic infection may last for 5 to 10 years on average until the development of AIDS, which occurs when the CD4+ count falls below 200 cells/mm3. At this stage, individuals are at risk for opportunistic infections such as Pneumocystis pneumonia, esophageal candidiasis, mycobacterial disease, cryptococcal meningitis, cytomegalovirus (CMV) retinitis, and toxoplasmosis as well as malignancies such as lymphoma and Kaposi sarcoma.

For purposes of studying the susceptibility to HIV or AIDS, researchers have classified patients with atypical outcomes into four major categories: 1. exposed uninfected (EU) individuals who remain uninfected after repeated exposure to HIV; 2. rapid progressors (RP) with uncontrolled viremia who progress to a CD4 count below 350 within 3 years; 3. long-term nonprogressors (LTNP) who are infected, yet maintain stable CD4 count and low level viremia for more than a decade; and 4. elite controllers or suppressors (EC/ES) who can suppress viremia for a decade or longer. These classifications have provided some insights into how viral and host genetics contribute to variations in outcome.

Differential diagnosis of symptomatic HIV:

Influenza, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), and other viral syndromes, immunodeficiency such as severe combined immune deficiency (SCID), B-cell and T-cell deficiency

Monogenic forms:

CCR5Δ32 was a mutation identified in 1996 that protected against HIV infection in homozygotes. The mechanism of action is that HIV gp120 binds to CD4 to gain entry into the cell using CCR5 as the chemokine receptor to which HIV binds. Strong evidence for this mutation in homozygotes and partially in heterozygotes has demonstrated delayed HIV disease progression.

Family history:

Not available

Twin studies:

In HIV-discordant monozygotic twins, a reduction of naïve T cells with skewing of T-cell repertoire has been noted in the HIV-infected cohort.

Environmental factors:

A few small studies have demonstrated environmental factors potentiating HIV progression and its sequelae. While tobacco abuse has not been shown to accelerate HIV progression, it has been shown to worsen opportunistic infections, particularly pulmonary infections. Stress and depression have additionally been shown to be associated with faster rates of progression. Additionally certain viral infections such as herpes simplex virus (HSV) increase risk for HIV transmission.

Genome-wide associations:

Genetic associations with disease outcome are numerous. Disease-associated genetic variants (single-nucleotide polymorphisms [SNPs]) provide insight into disease pathogenesis. The first genome-wide association study (GWAS) in HIV-1 disease identified several variants and the most clinically relevant variant is the HCP5 locus that tracks to the HLAB*5701 allele that is clinically validated in the management of HIV (Table 84-1). Subsequent studies have confirmed the KLA mapping as well as the chemokine co-receptor/ligand CCR5 loci.

Pharmacogenomics:

Screening for HLA B*5701 is utilized for screening for abacavir hypersensitivity when abacavir is being considered as a component of the antiretroviral regimen.

Diagnostic Criteria and Clinical Characteristics

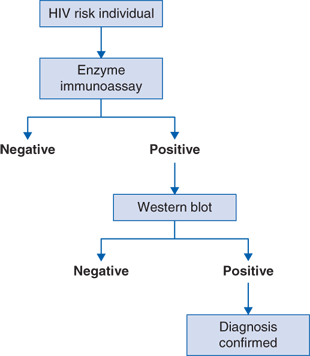

Diagnostic evaluation includes the following tests (Fig. 84-1 algorithm):

Positive (rapid) enzyme immunoassay

Positive confirmatory western blot

or

HIV RNA (viral load)

Once the diagnosis is made, further testing is recommended

CD4 cell count and percentage

HIV resistance testing (genotype)

Coreceptor tropism assays (when considering maraviroc)

HLA B*5701 testing (when considering abacavir)

CMV and Toxoplasma IgG testing

Sexually transmitted disease (STD) screening (eg, syphilis)

Cervical and anal cancer screening

Screening for latent tuberculosis

Viral hepatitis screening

An individual is tested either for general screening or for those who are at high risk. The enzyme immunoassay (EIA) is performed that is a rapid or point-of-care test with various forms (oral, blood). If the result is positive, a confirmatory western blot (WB) is performed. If the western blot is positive, the diagnosis is confirmed and the standard workup is recommended. The exception to this algorithm is that in the event of acute HIV, there is a seroconversion or “window” period in which antibodies to HIV are not yet detectable in the blood and therefore EIA and WB would be negative. In this situation, an HIV polymerase chain reaction (PCR) would be performed.

HIV disease is marked by three distinct stages, described below:

Acute seroconversion is observed symptomatically in half of new patients infected with HIV. It is associated with fever, flu-like illness, lymphadenopathy, and rash and may be confused with numerous other viral and nonviral syndromes such as secondary syphilis or acute toxoplasmosis. During this time, the viral load rapidly rises but a rapid immunoassay enzyme test may not detect the HIV surface protein before several weeks have passed, causing a falsely negative result. For this reason, the HIV PCR assay is more sensitive during this period from 2 weeks to 6 months and if suspicion exists for acute HIV, an HIV PCR should be performed concomitantly with serologic testing (Fig. 84-1).

Asymptomatic infection may last for 5 to 10 years on average until the development of AIDS. This may vary by individual and treatment guidelines discussed later. For treated patients, adverse effects include side effects, drug interactions, and increased risk for cardiac and other metabolic complications. These individuals require assessment of cardiac risk factors and age-appropriate cancer screening, as this group is at higher risk than the general population. As the CD4+ count drops below 500 cells/mm3, individuals are at increased risk for infections including esophageal candidiasis and HSV; hematologic effects such as anemia and thrombocytopenia; and malignancies including Kaposi sarcoma and lymphoma.

AIDS occurs when the CD4+ count falls below 200 cells/mm3 or when an AIDS-defining condition develops irrespective of CD4 count. At this stage, individuals are at risk for opportunistic infections and malignancies as previously described. Individuals whose CD4 count is below 200 should receive prophylaxis against Pneumocystis and those whose CD4 count is below 75 should receive prophylaxis against Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC).

The graph (Fig. 84-2) depicts the time course of CD4+ cells and HIV viral load through the natural history of HIV infection. The initial infection is marked by an acute rise in viral load that reaches a peak with weeks of initial infection. During acute infection before the viral load peaks, rapid enzyme immunoassay may not detect virus, giving a false-negative result. After the acute infection, the viral load gradually decreases down to the individual’s set point where the counts may remain stable for years. The CD4 count drops initially and then follows a more gradual progression and the individual may remain in this clinical latency or asymptomatic period for years until becoming symptomatic. Once the CD4 count falls below 200, the disease is classified as AIDS, which is an absolute indication for antiretroviral therapy and puts the patient at risk for development of multiple infectious complications.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree