Key Points

Disease summary:

Iron is an essential dietary mineral that can become toxic when present in excess quantities or in a reactive state.

Hereditary hemochromatosis (HHC) is defined as a biochemical state of iron overload complicated by end-organ dysfunction such as diabetes, cirrhosis, or cardiomyopathy.

It is critical to recognize the general presenting symptoms or family history of HHC as this disease can be fatal if undiagnosed, but is the rare genetic disease that can be cured if detected and treated early.

The HHCs are a group of monogenic diseases with a common pathophysiology that features disruption of mechanisms regulating iron homeostasis resulting in excess iron accumulation.

The most common, classical form of the disease is type 1 or HFE-linked HHC which accounts for 80% of cases in Caucasian populations. The other types are rare and panethnic.

There are four other well-defined types of hereditary hemochromatosis caused by loss-of-function mutations in five genes.

The common pathophysiology underlying HHC is failure to prevent a rise in blood iron levels as evidenced by the fact that all five proteins either sense or control the level of iron.

Hereditary basis:

Iron overload should only be attributed to hereditary causes after ruling out comorbid conditions such as other etiologies of liver disease or anemia that lead to secondary iron overload.

Types 1 to 3 HHC are autosomal recessive and result from loss-of-function mutations.

Type 4 is autosomal dominant due to heterozygous mutations of ferroportin with two distinct genotype-phenotype manifestations.

Differential diagnosis:

The key is to distinguish uncomplicated iron overload from complicated iron overload that includes HHC.

It is imperative to differentiate other causes of liver disease where iron accumulation is secondary (eg, alcoholic or hepatitis virus cirrhosis) from HHC.

Other genetic disorders such as anemias and porphyria cutanea tarda are associated with secondary iron overload but have additional features that distinguish them from HHC.

Diagnostic Criteria and Clinical Characteristics

All of the following

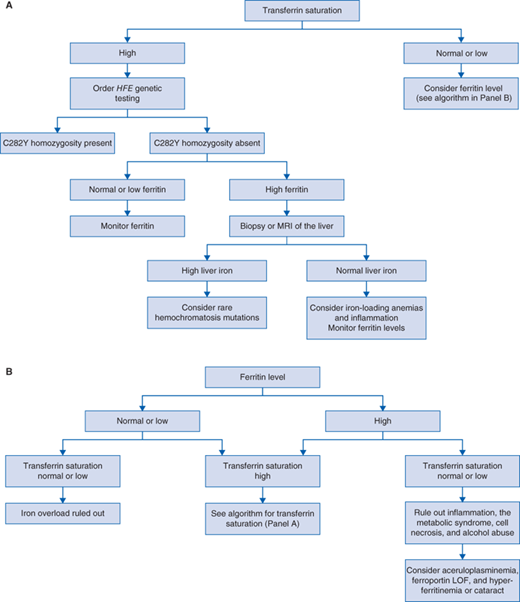

Primary iron overload usually evidenced as elevated plasma iron and transferrin saturation with hyperferritinemia without other identifiable cause of iron accumulation (Fig. 72-1).

Evidence of organ dysfunction is highlighted earlier in Table 72-1. Most commonly this manifests as transaminitis, diabetes, impotence, arthritis, and arrhythmias.

To prove hereditary etiology there must be evidence of two mutations in the same gene in types 1 to 3 or a single ferroportin mutation in type 4 disease (Table 72-2). In classical (type 1 disease), it is imperative that patients with two HFE mutations have not been misdiagnosed with HHC because the majority will not go on to develop disease due to reduced penetrance (see Counseling).

And the absence of

Other comorbid conditions that could explain the iron overload.

| System | Manifestation |

|---|---|

| Liver | Hepatocytic iron accumulation, hepatomegaly, transaminitis, fibrosis that can progress to cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, transplant, or death |

| Endocrine | Endocrine pancreatic islet cell iron accumulation resulting in insulin insufficiency and diabetes; anterior pituitary iron accumulation resulting in gonadotropin deficiency, impotence, and premature menopause |

| Heart | Iron accumulation triggering arrhythmia and restrictive cardiomyopathy and in juvenile hemochromatosis heart failure, transplant, or death |

| Joints | Synovial cell iron accumulation, arthropathy that progresses to chronic arthritis |

| Skin | Iron accumulation resulting in excess melanin production resulting in “bronze” appearance |

| Gene | Class | Type and Inheritance | Mutation Type | Detection Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HFE | HFE linked |