Key Points

Disease summary:

Stroke is an umbrella term for the rapid loss of neurologic function in a particular vascular territory, with symptoms lasting greater than 24 hours.

The causes of stroke are broadly defined as either ischemic or hemorrhagic.

Clinical manifestations depend on the vascular territory affected, with the middle cerebral artery (MCA) being most commonly affected.

Management of stroke involves identifying the onset and duration of symptoms, assessing and maintaining normal vital signs, evaluating whether the patient with acute stroke is a candidate for thrombolysis, and longer-term risk factor management.

Differential diagnosis for stroke:

Several phenomena may present similar to stroke, including transient ischemic attacks ([TIAs], which manifest as neurologic deficits lasting <24 hours), migraines, Todd paresis, head trauma, brain tumors, and metabolic and/or toxic insults (such as hypoglycemia, hypothyroidism, renal or liver failure, certain drug intoxications).

Monogenic forms:

Monogenic forms of stroke include (1) syndromes that feature ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke as the primary or key component, or (2) multisystem syndromes or conditions that contain stroke as a secondary component.

Family history:

A family history of early cardiovascular disease increases the likelihood for the development of ischemic stroke. A family history of cerebral aneurysms may be relevant for hemorrhagic stroke risk.

Environmental factors:

For ischemic stroke, the classical determinants of atherosclerosis, such as smoking, poor diet, obesity, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension can increase the risk for stroke, as can the use of certain medications, such as hormone replacement therapy.

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS):

GWAS findings of stroke as a clinical end point are relatively inconsistent, while GWAS of risk factors and intermediate traits, such as plasma lipids and hypertension, show much more consistency across studies.

Pharmacogenomics:

Preventive therapies for embolic stroke, specifically Coumadin (warfarin), show replicable associations with interindividual genomic variation. Also, interindividual differences in the susceptibility to serious side effects from statins, used widely in stroke prevention, appear to have a genetic basis.

Diagnostic Criteria and Clinical Characteristics

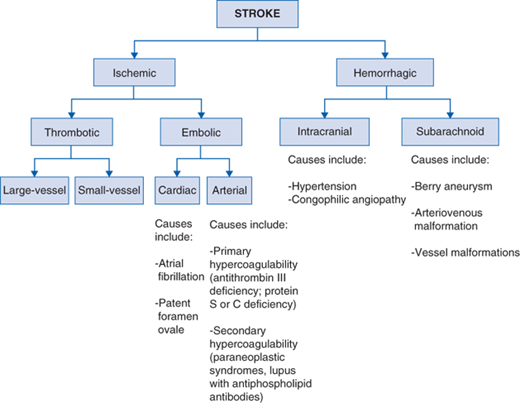

Stroke is defined as the rapid loss of neurologic function in a particular vascular territory caused by either ischemia or hemorrhage, with symptoms lasting greater than 24 hours. Ischemic strokes can be subdivided according to cause: thrombotic or embolic. Meanwhile, hemorrhagic strokes are subdivided according to location of bleeding: parenchymal (intracerebral hemorrhage [ICH]) or subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) (Fig. 17-1). The diagnosis of stroke depends on accurate history and physical examination, and confirmed by appropriate neuroimaging.

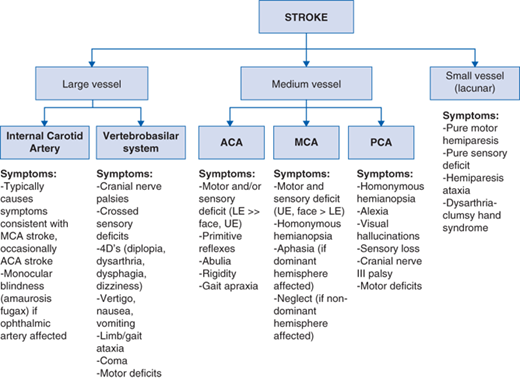

The exact clinical characteristics of a stroke depend on the vascular territory affected, with the MCA most often affected. See Fig. 17-2 for types of vessels affected and their respective clinical characteristics.

Several phenomena may present similar to stroke, including TIAs, migraines, Todd paresis, head trauma, brain tumors, and metabolic and/or toxic insults (such as hypoglycemia, hypothyroidism, renal or liver failure, certain drug intoxications). Of these, TIAs are most often difficult to distinguish from strokes, since the only difference between the two phenomena is duration of symptoms. Neurologic deficits secondary to TIAs resolve within 24 hours. Unfortunately, due to the need for early intervention with thrombolytic therapy in patients with ischemic strokes, time is often not enough to determine whether a patient’s symptoms are due to stroke or TIA.

Screening and Counseling

Monogenic forms: Once a firm molecular diagnosis has been made for a rare monogenic form of stroke or for the broader multisystem disorder that includes stroke as a component, family members can be tested in a cascade manner for the specific mutation.

Hemorrhagic stroke: Most forms of inherited cerebral aneurysmal disease have no molecular basis determined. When a strong familial tendency is suspected, relatives of a proband with cerebral aneurysms can be screened not with molecular techniques, but instead with noninvasive imaging technologies for clinically silent aneurysms, which if detected, can be pre-emptively treated surgically.

Common complex ischemic stroke: Family members of a patient who has suffered a common, later-onset ischemic stroke, should themselves be screened for the presence of modifiable risk factors, such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, or diabetes. Appropriate lifestyle interventions—diet, weight loss, and exercise—together with appropriate drug treatments can be instituted following clinical guidelines for the prevention of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease.

Management and Treatment

Timing is essential to the management of patients with stroke. Immediate management of patients presenting with symptoms suggestive of a stroke includes assessment of airway, breathing, and circulation (ABC), ensuring euglycemia and euvolemia, and evaluating underlying reversible or life-threatening causes. Determining the exact onset of symptoms is critical to determining whether the patient is a candidate to thrombolytic therapy.

Assess ABCs, check blood sugar to ensure not hypoglycemic.

Obtain accurate history, including exact onset of symptoms and potential causes for presentation.

Perform thorough physical examination to rule out immediate life-threatening causes of presenting symptoms (hypoglycemia, hemorrhage).

Neurologic examination with the aid of the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree