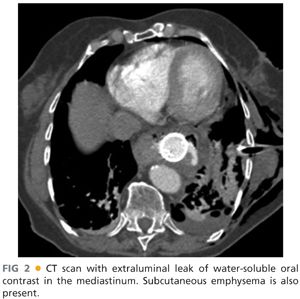

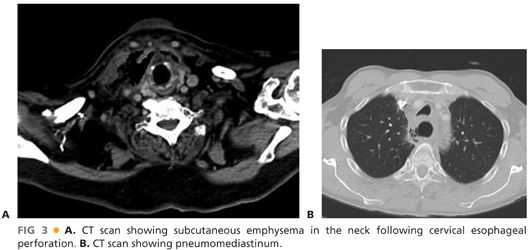

■ Cervical and thoracic computed tomography (CT) scans with oral contrast can be performed to diagnose esophageal perforations. An extraluminal leak of contrast medium can be seen in the prevertebral or pleural spaces (FIG 2). CT scan also allows for the evaluation of other potential causes of clinical presentation. CT scan is the investigation of choice when diagnosis is uncertain. Pneumomediastinum, pneumoperitoneum, and air in the subcutaneous tissues of the neck will often be seen in cases of esophageal perforation (FIG 3A,B). CT also allows for the evaluation of the neck, mediastinum, abdominal cavity, and pleural spaces, which can aid in operative incision planning and/or drainage planning in nonoperative cases.1

■ Gastrografin studies can also be performed and should be immediately followed by a barium swallow in the event of negative findings, as barium studies are more sensitive than Gastrografin. Water-soluble contrast should be avoided when tracheoesophageal fistula is considered in the differential. With CT scan and endoscopy, oral esophagograms are not usually necessary in the modern day diagnosis of esophageal perforation.

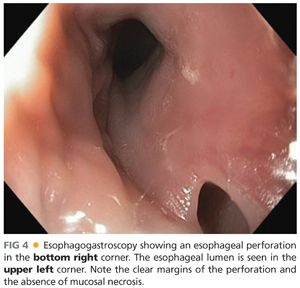

■ Diagnosis can also be made using endoscopy (FIG 4). Endoscopy should always be performed under general anesthesia in the operating room at the time of esophageal repair, exclusion, stenting, clipping, or decision regarding conservative management. It should always be performed by an experienced upper GI endoscopist and is very important in not only assessing the site of the perforation but also in evaluating for distal obstruction, quality of the esophagus, size of the hole, associated upper GI pathology, and mucosal quality/necrosis. It is primordial that insufflation be kept to a minimum in order to avoid increasing the extent of the perforation.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Preoperative Planning

■ Appropriate resuscitation is mandatory prior to surgical treatment. Diagnosis should be confirmed either by CT scan, water-soluble contrast/barium swallow, or endoscopy. This is critical as approaches to cervical, thoracic, and abdominal esophageal perforations are drastically different. Broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics should have been started as soon as the diagnosis is made.

■ We recommend on-table endoscopy under general anesthesia in all cases in order to precisely delineate the location, size, and extent of the hole and assess the quality of the esophagus (including evaluation of possible downstream obstruction). Additionally, endoscopy can be used as a treatment option (stenting, clipping) or as an adjunctive procedure during repair (perforation cannulation, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy, percutaneous endoscopic jejunostomy). In cases requiring thoracotomy, laparotomy, or cervical exploration, a flexible soft-tipped guidewire is typically placed through the perforation using endoscopy in order to make it simple and expedient to find the site of perforation during surgical exploration and minimize dissection (FIGS 5 and 6).

Positioning

■ Cervical perforation

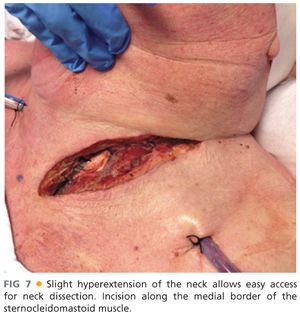

■ The patient is placed in dorsal position with a bolster under the scapulae to obtain a slight hyperextension of the neck. The endotracheal tube is secured to the right corner of the mouth and the head is slightly turned to the right side (FIG 7).

■ Upper two-thirds thoracic perforation

■ The patient is placed in left lateral decubitus with a double lumen endotracheal tube in place. The flexion point of the operating table should be located at the level of the 5th thoracic vertebra. An axillary roll is placed under the thoracic cage, two fingerbreadths below the left axilla to protect the brachial plexus. The table is flexed in order to open the intercostal spaces on the right side. The right arm is positioned anterosuperiorly to the head. Once positioning is adequate, the position of the double lumen endotracheal tube is confirmed with bronchoscopy and the right lung is isolated from ventilation.

■ Lower one-third thoracic perforation

■ The patient is placed in right lateral decubitus with a double lumen endotracheal tube in place. All specifics of positioning are the same as for the left lateral decubitus position previously described.

■ Abdominal perforation

■ The patient is placed in dorsal position with both arms abducted.

TECHNIQUES

CERVICAL PERFORATION REPAIR AND DRAINAGE

Skin Incision

■ The medial border of the left sternocleidomastoid muscle is identified. An incision is performed along the border of the muscle (FIG 7). The platysma is incised in the orientation of the skin incision.

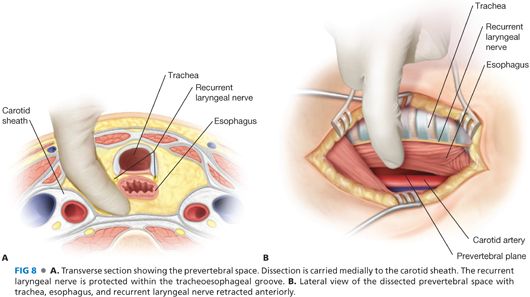

Dissection

■ The sternocleidomastoid muscle is dissected and retracted laterally, exposing the vessels of the neck. The carotid sheath is left intact and retracted laterally. If necessary, the middle thyroid vein is ligated and the larynx and trachea are retracted to the right. Care is taken to not damage the left recurrent laryngeal nerve, which lies in the tracheoesophageal groove. The prevertebral plane is entered, moving the esophagus anteriorly (FIG 8A,B). The entire space is dissected as far caudally as the carina.

Repair

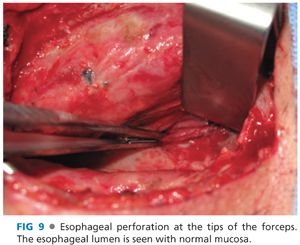

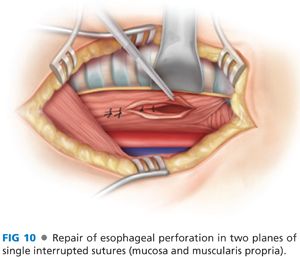

■ In most instances, the site of the perforation is not identified nor should any extensive amount of time be spent searching for it. If the perforation is visualized and easily accessible, it can be repaired. The first step of the repair is the lengthening of the opening in the muscularis propria as this is often smaller than the orifice in the mucosa (FIG 9). Once the entire length of the perforation is exposed, the repair is performed with single interrupted absorbable sutures on the mucosal plane and nonabsorbable sutures on the muscular plane (FIG 10). In most cases, the inflammation at the site of perforation will prevent easy identification of both mucosal and muscular planes. In such instances, it is appropriate to proceed with a single layer repair using single interrupted absorbable sutures. A rubber bougie should be placed in the esophagus orally to assure that the repair does not result in esophageal obliteration or significant stenosis.

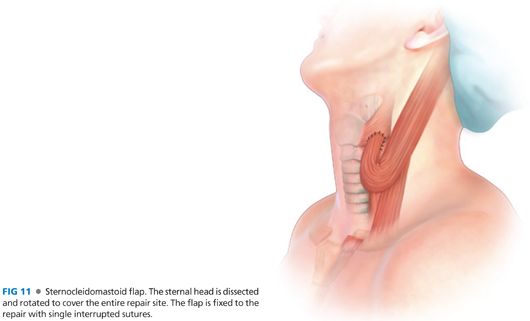

Sternocleidomastoid Flap

■ Leaks from primary repairs of esophageal perforations are common and it is preferable to protect the repair with a vascularized flap. For perforations of the cervical esophagus, the sternal head of the sternocleidomastoid muscle is detached using electrocautery and rotated to cover the site of the perforation. The muscle is fixed with multiple interrupted sutures around the repair. The muscle should be tightly opposed to the repair site and cover it entirely (FIG 11). In the case of concomitant tracheal injury, the flap should be placed in between the repaired esophagus and the trachea to avoid the formation of a tracheoesophageal fistula.

Drainage

■ Regardless of whether the site of perforation was identified and/or repaired, the prevertebral space is irrigated abundantly and drains are left in place. Drains are brought out through separate skin stab wounds.

Closure

■ The platysma is reapproximated in the superior portion of the incision with absorbable sutures. The skin incision is closed with staples.

THORACIC PERFORATION REPAIR AND DRAINAGE

Skin Incision

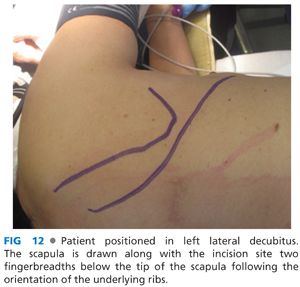

■ With the patient in lateral decubitus, left for perforations of the upper two-thirds and right for the lower third of the esophagus, the tip of the scapula is identified and an incision following the orientation of the underlying ribs is placed two fingerbreadths caudally (FIG 12).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree