This chapter aims to promote a deeper understanding of speech-language pathology practice in the acute-care hospital setting. Speech-language pathologists (SLPs) play a critical role in ensuring efficient, high-quality, and cost-effective patient care. Excellent clinical care for both communication and swallowing disorders in the acute-care setting requires strong and highly sophisticated clinical skills that are patient-centered and evidence-based and reflect best practice. These skills need to be informed by a balance between sophistication in understanding the clinical conditions and the medical procedures that affect the patient, and a thorough understanding of the health system continuum of care. Additionally, some key drivers for the current acute-care system have to be considered by the SLP. These include interprofessional practice and communication, cost-reduction and cost-containment measures, and a focus on quality and safety that is aligned with the goals of the particular inpatient unit and the hospital as a whole.

15.1.1 The Acute-Care Environment

Acute care involves the diagnosis and treatment of active or acute health conditions, and hospitals play an important role in delivering this type of care. Acute-care hospitals are diverse in their organizational structure and mission and vary in the scope of services delivered. No matter whether they are community or tertiary care centers, acute-care hospitals are typically complex, fast-paced, and characterized by a rapid progression toward discharge. Patients are admitted for medical management, invasive procedures, and surgical interventions as a result of a serious illness or condition, or for the sequelae of an initial trauma or insult. 1 Patients’ dynamic and frequently unstable medical conditions demand frequent monitoring and assessments. The patient’s health care team works collaboratively to ensure effective medical intervention, prevention of medical complications, and timely discharge. Rehabilitation, recovery, and healing continue to occur across the continuum of care or at home after discharge from the hospital.

The term acute-care hospital is broad in definition, and the acute-care hospital is characterized by a distinguishing range of characteristics, such as hospital size (including the number of inpatient beds), geographic area, specialty, population served, affiliation, and profit status (see ▶ Appendix 15.1 [p. 217]). In the United States, hospitals must adhere to performance standards established by regulatory bodies. For example, the Joint Commission (JC) is an independent, not-for-profit organization that evaluates and accredits health care organizations and programs to ensure high-quality and safe patient care. 2 All hospitals must adhere to regulations established by JC in order to receive reimbursement from Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurance. 1, 3 Other characteristics apply to all hospitals: physicians admit patients and are ultimately responsible for directing care, while other health care professionals, such as nurses, respiratory therapists, physical therapists, and SLPs, provide critical services. 1 Some hospitals provide specialty care (e.g., ophthalmology and otolaryngology) or care of burn patients, but most are general hospitals with a full spectrum of medical departments, such as internal medicine, surgery, cardiology, neurology, etc. Other departments in a hospital provide nonclinical services (e.g., police and security) or clinical services (e.g., pharmacy). In acute settings, speech-language pathology services are typically organized as either individual autonomous departments or as part of a larger integrated service, usually rehabilitation services. However, in some highly specialized institutions, SLPs can be found in the departments of neurology, otolaryngology, or pediatrics as well as in the rehabilitation services.

15.2 The Transformation of Health Care in the United States

One cannot address the topic of speech-language practice in the acute-care setting without considering the dramatic and rapidly changing health care environment. The causes are multifactorial but notably relate to insurmountable and unsustainable health care costs, serious concerns about quality of care, the burgeoning aging population, advances in technology, demands imposed by regulatory bodies, patients’ expectations and their easy access to health-related information, and health care disparity, including unequal access to care. 1, 6, 7, 8 National health care reform targets cost reduction and improvement in the overall quality and safety of health care, with the expected outcome of improving the health of all Americans. 8, 9, 10

15.2.1 Health Care Cost and Quality

Changes in the delivery of acute medical services across the United States are being implemented due to a number of governmental reforms created to guide local, state, and national efforts to improve the health care system. The national strategy focuses on improving the overall quality of care by making care more patient-centered, reliable, accessible, and safe; on improving health by supporting proven interventions and preventive is preferred AmE measures; and on reducing cost for individuals, families, employers, and the government. 8 Serious problems with quality and cost have been well documented. Although health care cost is reaching unaffordable levels, higher cost does not translate into higher quality. A variety of studies have demonstrated serious problems with the quality of health care, ranging from high rates of medical errors, preventable adverse events in health care settings, and preventable hospital admissions and re-admissions. Government programs are being implemented to stimulate innovation, to improve quality, and to decrease cost. New methods of payments, including those based on incentives and penalties or bundled payments for population management, encourage groups of providers (i.e., hospitals, physicians, and other clinicians) to coordinate care, to prevent complications, and to improve outcomes. 10 The changes in the health care system have direct implications for the SLP in an acute-care setting, trends described in an Institute of Medicine (IOM) review on health professionals’ workforce and services. 11

From acute treatment to chronic prevention and management: The goal is to manage chronic illnesses and disability through preventive measures and to avoid hospitalizations and complications that increase cost of care.

From inpatient setting to home and community: Patient-centered medical homes focus on keeping the patient at home using team-based care and technology to provide care.

From cost unaware to price competitive: Most people are unaware of the cost of care. Increased transparency and public reporting regarding charges for diagnostic tests and procedures are increasing consumer awareness.

From professional prerogative to consumer responsive: The traditional inpatient orientation of health care gives the professional (e.g., physician, nurse) the prerogative to exercise power. Patient-centered care means the patient and family have a voice in determining goals of care.

From traditional practice to evidence-based practice: Clinical decision making and interventions require strong evidence, based on applied and clinical research.

From information as record to information as tool: The implementation of the electronic medical record (EMR) provides opportunities for timely and effective intervention and communication across health care systems and providers. Additionally it provides a platform for data collection and research initiatives to ensure effective and consistent management of patient populations.

From patient passivity to consumer engagement and accountability: Internet access allows patients to have health-related and health care information easily available.

From individual practice to team approach: Cost reduction, higher quality, prevention, and better outcomes are promoted by team-based care.

15.2.2 The Interprofessional Health Care Team

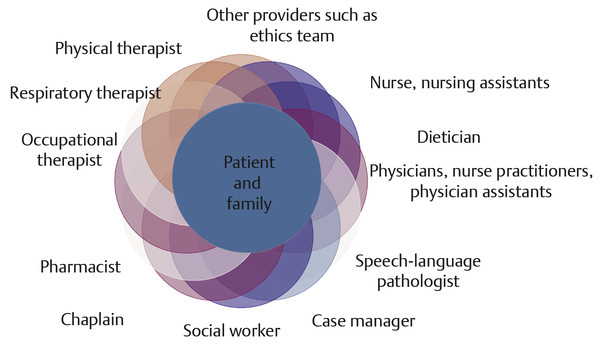

Health care reform efforts to control cost have led health care providers to shift focus to a safer, better, and less costly approach to care that relies on effective collaboration, care coordination, and a team approach to care. 11 Team-based care is a strategy steadily being adopted nationwide to reduce unnecessary spending and to coordinate services so that high-quality care is delivered more economically and safely. 11, 12 Early research evidence is showing a positive effect on care. 11 The interprofessional health care team has been defined as a group of clinicians from different disciplines who collaborate effectively with the patient and each other to address complex patient situations and problems that cannot be managed by one discipline alone. 11 Interprofessional patient care, highlighting the expertise of each team member ( ▶ Fig. 15.1), is especially crucial in managing patients with an acute medical condition associated with chronic illness. The SLP plays a unique and important role in identifying conditions that may be outside of the physician’s expertise (communication or swallowing), that can contribute to the complexity of care needed, and that are likely to shape outcome and discharge. Additionally, the SLP may identify new health concerns that increase a patient’s risk for infection or for complications of dysphagia, or the SLP may identify cognitive impairments that will prevent the patient from safely returning home alone.

Fig. 15.1 Interprofessional team-based care.

15.3 The SLP in Acute Care: A Revised Model of Practice

Historically, SLPs in acute-care hospitals have been viewed as consultants in caring for the patient and assisting patients, caregivers, and other health care providers to prepare patients for the rehabilitation process. 13 SLPs are called upon to provide differential diagnosis of communication and swallowing disturbances, to assess severity, to develop and implement short-term treatment recommendations, to monitor changes throughout the patient’s hospital course, and to communicate regularly with the patient, family, and medical and allied health care team. Throughout the patient’s hospital experience, the SLP concentrates on the patient’s discharge needs and plan for follow-up. 13 Although in today’s acute-care setting speech-language pathology remains a consultation service, the scope of practice has expanded, giving our service a broader role within the patient’s acute-care team. In essence, the traditional consultative model warrants a sweeping shift in focus that goes beyond the SLP’s acting as a consultant who provides professional advice to a physician and medical team.

Current service-delivery models of health care across the continuum of care are evolving, but they consistently focus on

Improving the quality of care delivered

Making the care we provide safer, more effective, efficient, timely, and equitable

Ensuring that care remains patient- and family-centered

Making care more cost effective

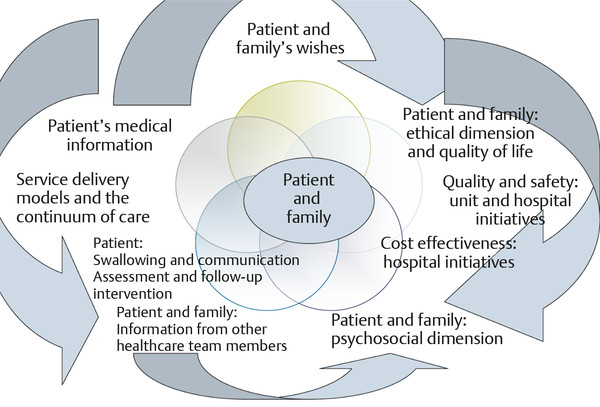

In the acute-care setting, a patient’s episode of care has a well-defined beginning and end, but as our model ( ▶ Fig. 15.2) suggests, the patient-care process cannot be viewed in a linear, step-by-step fashion. The process is dynamic, warranting continuous clinical reasoning and decision making regarding patient care, with multiple factors influencing and impacting the decisions made by the health care providers. The SLP is responsible for recognizing the multiple factors affecting his or her clinical decision making.

Fig. 15.2 The SLP in acute care: a theoretical model for patient management.

The new patient-centered model of acute-care SLP practice includes four essential dimensions: (1) assessment and management of swallowing, speech, language, and cognitive components; (2) identification of features of the patient’s current or predicted status or behavior that contribute to any concerns about safety, quality of care, or cost; (3) the patient and family’s values and goals for care; and (4) practice within an interprofessional team.

At the center of the model are the patient and family. When care is patient- and family-centered, clinicians develop a relationship with patients and families and engage them in the decision-making process. As a result, the patient and family have the opportunity to fully participate and to convey personal values and expectations of care; personal, cultural, and psychosocial aspects are as important to consider as the goals of medical intervention and findings of the communication or swallowing assessment. With the emphasis on patient-centered care, the SLP is accountable to the patient and family, warranting patient-specific advocacy, effective communication, collaboration, and decision making. The interprofessional team approach to care, which is based on timely and effective communication among health care professionals, ensures that relevant information is considered. With a thorough understanding of the economic and quality drivers within a system of care, the long-term goals of effective, efficient, timely, high-quality care in the most appropriate setting are embedded in the SLP’s clinical recommendations and communication with the patient, family, and interprofessional team. Adding issues of safety, quality, and cost reduction to considerations about assessment, treatment, and post-discharge status and recommendations is therefore an essential part of SLP practice. SLPs need to understand hospitals’ safety and quality initiatives, unit-specific protocols, and the myriad aspects of patient-care experiences encountered in the emergency department, intensive care unit, and general care units.

In order to effectively deliver care in this new model, the SLP requires considerable advanced knowledge and skill. The following represents a list of knowledge areas that are critical for the practice of acute-care speech-language pathology, and that extend beyond the basic knowledge of speech-language pathology clinical information:

A thorough understanding of major body systems, interventions, and the interplay of chronic and acute conditions and their impact on cognition, speech, language, and swallowing.

Knowledge and understanding of the ethical and psychosocial domains that drive patient choices and decisions and influence SLP recommendations and advocacy.

Knowledge and understanding of the hospital’s medical services and health professionals comprising patient-care teams.

Knowledge and understanding of care delivery systems across the health care continuum.

Knowledge and understanding of health care issues, national quality and safety measures, and their impact on the institution.

Knowledge of federal and state cost-containment and pay-for-performance programs affecting acute-care settings and the impact on the institution.

An example of the role of the SLP in this new model relates to a hospital initiative for reducing length of stay and avoiding re-admissions as essential to reduce cost. Not only is it critical to provide a prompt response to a consult to evaluate swallowing function, but also the impressions and recommendations have to take the patient’s prognosis and disposition plan into consideration. Sometimes the SLP may feel pressured to recommend nonoral means of nutrition given patient acuity and impending discharge to the next level of care, as is the case when a medical team may be eager to place a gastrostomy tube to expedite the patient’s discharge. A discussion with the patient and family may reveal the importance of food in family gatherings and their lack of understanding regarding dysphagia and the potential for speech-language treatment to facilitate safe swallowing. When the swallow evaluation determines that the patient can swallow safely under certain conditions, a discussion with the medical team and the patient and family may result in deferring placement of the gastrostomy tube and implementing the SLP’s recommendations. In this way, the SLP contributes to (1) the patient’s quality and experience of care and (2) cost reductions by preventing unnecessary procedures. The patient in the example just cited warrants follow-up swallow treatment after discharge, and it is important to avoid a readmission with complications from dysphagia. Therefore, the hospital-based SLP must ensure verbal and written communication with the SLP caring for this patient at the next level of care after discharge from the acute setting. At times, these recommendations, which may cause slight delays in discharge or add the need for outpatient follow-up services, can be viewed by others as impediments to timely patient management. It can be useful and informative in these situations to help the other members of the team appreciate the cost/safety/quality-of-life benefits of the SLP’s recommendations

The application of this new model is not limited to patients with dysphagia, as in the example of an SLP’s advocating for a supervised environment after discharge for a previously independent patient who lives alone and now presents with cognitive deficits. The SLP may need to prevent a premature discharge when the care team has not recognized the patient’s need for 24-hour supervision at home. Consideration of the delicate balance between timely and premature discharge and the factoring in of the myriad variables that can tip the outcome favorably or unfavorably must now become part of the SLP’s habitual approach.

15.4 The Consultation Process

Speech, language, and swallowing consultations can be requested from multiple services, but a few, such as otolaryngology and neurology, are usually major referral sources. Other frequently referring services include pulmonary and critical care medicine, gastroenterology, general surgery, palliative care, hospitalists, and gerontology ( ▶ Table 15.1).

Neurology | Cerebrovascular disease, neurodegenerative disorders, brain tumors |

Otolaryngology | Head and neck cancer, vocal fold paralysis |

Neurosurgery | Brain tumors, cervical spine instability, aneurysms |

Pulmonary | Aspiration, tracheostomy and ventilator requirements |

Gerontology | Dementia, delirium |

Medicine | Infection, delirium, deconditioning, gastroesophageal reflux, pneumonia |

Oncology | Lung cancer, esophageal cancer, leukemia, lymphoma |

Thoracic surgery | Lung and heart transplant, cardiac surgery, esophagectomy, tracheal resections |

Palliative care | Dementia, metastatic cancer, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) |

A written order or consult is required to evaluate and treat an inpatient in the acute-care context, and in most cases a 24-hour response time is expected. Physicians, nurse practitioners (NPs), or physician assistants (PAs) generate consultation requests, but the need for the SLP may also be identified by nurses taking care of the patient, other rehabilitation professionals, or the case manager who is dedicated to the discharge process. The acute-care SLP should have a comprehensive understanding of the practice patterns and typical clinical questions of major referral services. For example, stroke patients are referred for an assessment of aspiration risk within 24 hours of admission or before administration of oral medication, or surgically treated patients with head and neck cancer undergo swallowing evaluations on postoperative day 7. Some specialty services develop a specific order set, which may involve an SLP referral; for example, an order set may be for care of a patient with a tracheostomy and can include collaboration for tracheostomy downsize and decannulation, speaking valve readiness and training, and assessment of alternative communication for a patient unable to use a speaking valve, or the order set may require preoperative counseling and electrolarynx training for a patient scheduled to undergo a total laryngectomy.

15.4.1 Reasons for Consultation

In spite of the wide variety of services requesting SLP consult, there seems to be a set number of reasons for consultation ( ▶ Table 15.2). The SLP is responsible for understanding the nature of the request so that the evaluation is completed in a timely, targeted, and accurate fashion directed at the question being asked. Usually, the physician’s referral contains a brief history of the patient and the reason for the referral. Sometimes consultations are predictable based on the admitting diagnosis. When the referral question is vague or ambiguous, clarification is required prior to the evaluation. Direct conversation may reveal questions that were not originally considered. This can also provide a great opportunity for educating referral sources, providing them with important concepts and guidelines for future referrals. For instance, the patient with a traumatic brain injury and tracheostomy tube may require an evaluation of swallowing, but speech production may also require evaluation because of trauma involving the velopharyngeal mechanism. Single or multiple questions may drive a consult request, including assistance with the process of differential diagnosis among disease entities or pharyngeal vs. esophageal dysphagia.

|

The location of the patient within the hospital may provide clues regarding medical fragility (intensive care unit or respiratory care unit), specialized services (thoracic surgery, burn unit), and the presence of major system illness necessitating admission (neurology, oncology, trauma surgery). However, highly complex patients may also be found on general medical or surgical units.

Regular collaboration with frequent referral services will help the SLP preempt the consultation by obtaining a timely order and expediting evaluation and treatment. In many instances, however, the consultation request is unpredictable and the patient’s communication and swallowing needs may be the result of an unanticipated complication of the illness during that particular hospitalization. For example, a patient who underwent cardiac surgery and subsequently suffered a perioperative vocal fold paralysis may demonstrate unexpected voice and swallowing dysfunction. Because of the rapidly expanding scope of practice of SLPs, new referral and collaborative relationships are constantly being formed; thus, in many facilities, high-volume referrals may stem from a variety of services.

15.4.2 Timing and Urgency of Consult

Timing of the evaluation following the request can influence the accuracy and validity of the results of the evaluation. It is important for the assessment to occur after consideration of factors that may improve validity or impact safety. For example, the somnolent patient undergoing alcohol withdrawal may not be appropriate for a cognitive evaluation until his sedating medications are decreased and his attention or alertness improves. Similarly the patient who recently underwent a bronchoscopy with anesthesia may need to wait a few hours before regaining sufficient airway protection for a swallowing evaluation. In another scenario, a procedure may be planned or under way that alters the patient’s speech, language, or swallowing status such that a preprocedure evaluation may not be helpful to further management; for example, a patient undergoing chemoradiation therapy for head and neck cancer who is experiencing mucositis and odynophagia would need to wait until the acute side effects have subsided before participating in a videofluoroscopic swallowing study (VFSS). Similarly, a patient with a brain tumor who has just undergone surgical resection with postoperative cerebral edema would most benefit from cognitive-linguistic assessment and treatment planning after the initial brain swelling has subsided. Finally, a patient in the active process of weaning from a ventilator may benefit from delaying a swallowing evaluation until respiratory function has stabilized.

Alternatively, understanding the urgency of a consult request allows SLPs to predict and to manage their caseloads and to respond in a timely manner. With an urgent request, the results of a swallowing evaluation may determine the safest route of medication administration, oral or nonoral, and this could affect care and outcome. Equally urgent, a patient with a traumatic brain injury ready for discharge may require a cognitive evaluation to ensure an appropriate disposition, such as acute rehabilitation, long-term rehabilitation, or home care. The SLP has the responsibility to contribute to the discussion of candidacy for rehabilitation and the appropriate level of rehabilitation services and to advocate for the highest level of rehabilitation care by demonstrating the patient’s potential for recovery.

Sometimes a consult is requested to provide information regarding a patient at the end of life or to assist in providing a means of communication for a patient to express his or her wishes in a manner that is as effective as possible. 14, 15, 16 This can be achieved by helping to establish an eye-gaze communication system for a patient with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, establishing a consistent Yes/No response system for a patient with aphasia so that the team can honor the patient’s preferences, or providing voice amplification for a cancer patient too deconditioned to phonate, so that the patient may express consent or wishes.

The SLP scope of practice 17 helps in determining whether the consultation request is appropriately directed to the SLP service. For example, issues related to gastroesophageal reflux or emesis may cause aspiration pneumonia, but management is best directed to gastroenterology. Similarly, management of a patient with an acute delirium induced by a toxic-metabolic disarray, polypharmacy, and/or lengthy hospital stay requires medical stabilization, which is best managed by psychiatry and/or neurology. It is important that the SLP be aware of the confines of their own scope of practice and that the SLP clearly communicate the rationale for nonintervention with the referring service as indicated.

15.5 Principles of Intervention in the Acute Inpatient Setting

In the acute-care setting, one of the most essential clinical skills for effective SLP practice is expert diagnostic ability, similar to the problem-oriented approach used by physicians. 18 A strong clinical foundation and experience to competently address the swallowing and communication needs of the patient are at the core of good practice and are essential for every practitioner. In order to best answer the consultation question, provide the most accurate diagnosis, and obtain valid and reliable information, the clinician needs to understand the patient, the nature and complexity of the acute illness, and its anticipated course. A solid grasp of these factors is as important as the characteristics of the specific communication or swallowing deficit in guiding management. Furthermore, the rapidly evolving status of the patient in the context of the relatively short hospitalization stay will necessitate timely evaluation with clear impressions and plan, ongoing monitoring, and frequent changes to the plan of care. 19

15.5.1 Core Constructs That Guide the Acute-Care Intervention

Understanding of Illness and the Nature of the Acute Problem

The SLP assessment begins with a process of comprehensive information gathering that leads to the development of a patient history, understanding of the patient’s background, and determination of the factors that may affect the patient’s current performance. The goal is to understand the information and to integrate it into a coherent patient story that guides the assessment process and scope, and that provides the framework for further diagnostic testing. 20 In addition, the SLP should seek to understand the current status of the patient’s medical work-up, pending tests, current medications that may affect the patient’s performance, and the likely hospital timeline.

In order to determine which factors in a patient’s medical history may have direct (or indirect) influence on the speech-language pathology exam, the medical SLP must have a strong foundation of knowledge about diseases, pathophysiology of illness, body systems, medication effects, 21 and medical tests and procedures. Some diseases and disorders may directly impact cognitive, communicative, or swallowing behaviors, such as brain neoplasms or laryngeal cancer, while others may have a less direct, but nonetheless critical, impact, such as diabetes or liver disease. Chronic diseases can negatively affect the patient’s overall health, strength, and endurance. Since a substantial component of management of patients in the acute-care situation is risk prediction, it is important to assemble an accurate picture of factors that might contribute to risk.

A skilled clinician has knowledge of a broad base of common clinical presentations, symptoms, and patient complaints that he or she uses to detect patterns and to understand the clinical sequelae of the multitude of diseases he or she may encounter. Many medical resources are available in print and electronically to provide clinicians with understanding of diseases, current best practices, and the anticipated symptoms and treatment ( ▶ Table 15.3). An experienced medical SLP will use the data-gathering period to enhance the effectiveness of the search for diagnostic patterns of symptoms and patient characteristics seen in previous clinical encounters. 22

Information on the effects of medications on swallowing, cognition, and communication |

|

Medical Resources |

|

Electronic Resources |

|

Multiple sources of information can be tapped for the relevant data, including

Medical chart review of current hospitalization

History gathering of past illnesses, surgeries, other hospitalizations

Discussions with other team members: nurse, physician, allied health professionals, case manager

Patient/family interview

The clinician needs to make note of, and to understand, the following patient characteristics (see ▶ Appendix 15.2 [p. 224]):

Current hospitalization course: It is important to review the reason for the admission, the circumstances of the onset of the acute event, timing of the presenting symptoms, and the nature and course of the patient’s current illness. This review includes results of diagnostic tests, such as imaging (CT scans, MRI, chest radiographs), cardiac and pulmonary function testing (e.g., echocardiogram and bronchoscopy), and laboratory data that may provide information regarding infection, dehydration, and malnutrition. The SLP should assemble information regarding the patient’s management to this point, such as surgical procedures, need for invasive ventilation, drug therapy, and the patient’s overall response to the treatments. To make sense of the information, it may be helpful to organize the aspects of the hospital course into body systems, such as pulmonary, cardiac, neurologic, and gastroenterologic, paying more detailed attention to the systems that would have a direct effect on the domains relevant to the SLP.

Nutrition and cognitive function over the course of the hospitalization deserve close attention when gathering information. The route of nutrition delivery (e.g., orogastric tube, nasogastric tube, intravenous) during the hospitalization should be defined, and the SLP should assess whether consistent nutrition has been affected by self-removal of nasogastric feeding tubes or gastroparesis causing regurgitation or emesis.

With respect to cognitive status, it is important to learn how the patient has reacted to hospitalization; for example, confusion, delirium, somnolence, and agitation are behaviors that, if persistent, affect the management plan.

Previous medical and surgical history: Previous hospitalizations for the same illness or other illnesses and previous procedures and testing provide important clues regarding chronicity of the condition, complexity of the disease process, and whether previous interventions have been successful. Furthermore, a history of dysfunction in one system may directly contribute to current functioning of another system; examples include dementia, psychiatric illness, progressive neurologic disease, or radiation therapy to the head and neck─all of which can affect speech and swallowing.

Psychosocial factors: These important factors include family structure and dynamics, level of independence at baseline, educational background, employment situation, cultural values, and languages spoken, all of which affect the care the patient may require upon discharge.

Current status: Understanding the patient’s medical status at the time of the evaluation, as well as deriving an understanding of the likely course of the patient’s condition(s) from this point onward, is crucial to the diagnostic process. The medical chart details the patient’s hemodynamic status, cardiac function, pulmonary function (including oxygen requirements, pulmonary treatments, and the patient’s response), and cognitive and behavioral status, such as orientation, awareness of condition, level of agitation or somnolence, and ability to communicate, as well as the need for nonoral nutrition, invasive ventilation, medications, procedures, etc. The development of a plausible therapeutic plan can be accomplished by determining overall patient behavior. The need for restraints or inability to cooperate with assessment likely signifies a patient’s limited ability to participate in feeding/swallowing activities. The patient’s level of pain (local or global) may hinder accurate assessment as well. Is there any planned procedure that may interfere with the speech-language evaluation or require rescheduling of speech-language intervention? Will a recently performed medical or surgical procedure affect the SLP’s findings, such as bronchoscopy? Does the patient require significant sedating medications to manage his/her behavior and, if so, do they interfere with the patient’s ability to participate in an evaluation?

Safety precautions: Prior to initiating the evaluation, safety precautions should be ensured. These may range from standard precautions, such as completion of hand hygiene before and after entering the patient’s room, to fully understanding medical restrictions, hemodynamic status, and any upcoming or just completed procedures that may render the patient unsafe or unable to take anything by mouth for a specified period of time (e.g., transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE), upper GI series (UGI), bronchoscopy, etc.). Similarly, because patient status can fluctuate, it is imperative that, before all follow-up visits, the SLP confirm with the nurse and check daily orders regarding patient’s recent events, current status, and changes in diet orders.

Safety factors to consider include

Bed restrictions–Is it safe for the patient to be out of bed? Does the patient require a bed rest order?

Head of bed elevation precautions/restrictions–Is it safe for the patient’s head to be fully elevated for the SLP evaluation and for meals? Does the patient need to lie flat? Does the patient require a brace in order to sit up?

Feeding/oral intake status–Does the patient currently have an NPO order (nothing by mouth) for any particular medical procedure that precludes a swallow evaluation and diet initiation at this time? Are there any fluid or free water restrictions that would affect the amount of fluid/water that can be provided? Does the patient have any food allergies that should be noted to guide the foods presented?

Restraint status–Does the patient require restraints and can they be removed during the speech-language session?

Hemodynamic status/stability–Is the patient’s medical and respiratory status stable or is the patient currently too fragile for oral intake? Is the patient stable enough to be taken off the floor for a VFSS and is nurse accompaniment required for monitoring?

Infection control/contact precautions–What infection control precautions must be followed when entering the patient’s room, such as gloves, gowns, masks, and hand washing?

Medications: Medications can directly affect a patient’s state of arousal, speech, or swallowing, can exacerbate cognitive-communication deficits, and/or can impact restoration of health. 21 Youse 21 states, “It is recommended that speech-language pathologists thoroughly investigate any medication a patient may be prescribed to determine if and how it may affect cognitive-communicative ability.” It is useful to have resources and references that describe the effects of prescribed medications ( ▶ Table 15.3).

Code status and patient wishes: These factors include the patient’s preferences regarding life-sustaining measures, health care proxy, and orders regarding the patient’s or family’s desires about intubation, resuscitation, and enteral nutrition. Alignment of SLP goals with the patient’s code status and defined life-sustaining treatment wishes is essential to making recommendations and determining how best to provide care. For example, a patient with clearly defined preferences for no alternative hydration or nutrition may best benefit from intervention that supports patient decisions, promotes quality of life, and educates the patient and family about ways to minimize distress and discomfort, rather than intervention that limits certain food items or alters diet consistencies.

Discharge planning/status: It is important for the SLP to be aware of the overall disposition and prognosis and to have a general sense of the immediacy of the discharge and the level of care being considered. If the patient will be going home, it is important to ascertain the level of family support and how it may interact with the recommendations of the SLP, as well as insurance issues that may curtail outpatient care. These factors are critical in the attainment of discharge goals and for a successful outcome for the patient.

The following case example demonstrates how understanding the nature of the illness and the patient’s current medical status can affect the SLP.

Mr. B, a 90-year-old male, was admitted from his nursing facility with cough and hypoxia as a result of recurrent aspiration pneumonia. He was reportedly “choking on his meals” at the nursing facility. He has a history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and severe esophageal dysmotility with reflux due to chronic opioid usage and a noted hiatal hernia. He had been hospitalized nine times in the previous 2 years for hypoxia, cough, and pneumonia. The speech-language pathology service was consulted during two of his last admissions secondary to chest X-ray findings indicative of pneumonia and reports of choking. A videofluoroscopic swallow study (VFSS) was completed 1 year prior to the current admission. The VFSS documented a mild oropharyngeal dysphagia primarily characterized by delayed airway closure, resulting in trace laryngeal penetration and aspiration with thin liquids prior to airway closure. The patient sensed the aspiration on most occasions and coughed the material out of his airway. The remainder of his oropharyngeal swallow function was adequate. The strategy of small, single sips of water with frequent breaks in between was successful in eliminating the airway penetration. The findings of the swallowing evaluation with minimal airway invasion and a robust airway protection response did not align with the degree of pulmonary compromise necessitating the frequent hospital admissions for pneumonia. Alternative explanations were necessary. Extended conversations among the health care team, the patient, and the patient’s daughter revealed a history of regurgitation and heartburn that possibly explained the symptoms and the etiology of the pneumonia but that would require further investigation. The patient and his daughter declined a gastroenterology consultation to manage the esophageal dysphagia and wished to continue with an oral diet given the patient’s desire to eat. Thus, it was determined that likely further aspiration events could not be prevented despite lifestyle changes to minimize reflux. The decision was made to initiate a “do not hospitalize” order and the patient was discharged back to his nursing facility with routine antireflux precautions.

Patient/Family Interview

By completing a thorough and sensitive patient/family interview, with particular attention to presenting symptoms and their duration and severity, the SLP can begin to determine if the nature of the problem is acute or chronic ( ▶ Table 15.4).

Components of the Interview | Rationale |

1. Greetings and ensuring patient comfort | Clear introductions help to set the stage for an effective interaction. Sit down to speak with the patient. |

2. “Calibrating” the interview | Valuable information about the patient’s communication style and behavior is obtained, as well as a tentative list of problems. |

3. Questioning, listening, and observing | “What kind of problems have you been experiencing?” and other open-ended questions encourage the patient to report problems before the clinician initiates a more detailed inquiry. |

4. Facilitation techniques | Encourage and guide the patient’s spontaneous report while exerting as little clinician control as possible. |

5. Patient’s chief complaint | “Which of your problems concerns or bothers you the most?” will allow the clinician to understand the importance of the problem to the patient. |

6. History of present illness (HPI) or story of illness | Following leads obtained during the discussion, the clinician collects pertinent information about the relevant diagnosis, looking for symptom complexes or diagnostic patterns that assist in clarifying the diagnostic hypotheses. |

7. Transitional statements | Before proceeding with each new section, make a clear transitional statement. |

8. Past medical history, social history, symptom checklist | Completes the patient profile. |

9. Closing the interview | Ask the patient if there is anything else he or she would like to share regarding his/her concerns. |

Based on Lichstein’s elements of a medical interview. 23 | |

Not only is the interview a powerful diagnostic tool that guides the clinician’s next steps in the process, but also it provides the SLP with an opportunity to establish rapport and develop trust, which must occur quickly in the acute environment. 23 Furthermore, Lichstein 23 states, “The interview is a collaborative effort between physician and patient.” An open question format will yield the most information. The SLP should be sensitive to the fact that he or she is one of several health care providers requesting information that day, often with similar questions.

Throughout the interview, the SLP can keenly observe the patient for accuracy of responses, communication effectiveness, overall mental status, and level of concern and awareness regarding the presenting deficit. These observations will also help to target the assessment, which is essential, because patients with acute illnesses likely cannot pay attention for a long period of time.

Hypothesis Testing and Differential Diagnosis

Based on information gathering and history taking, the SLP understands the reason for the hospital admission and the nature of the clinical question, and begins to formulate a hypothesis about the potential or anticipated cognitive-communicative and/or swallowing disorder. The formulation of a logical and thoughtful hypothesis directs further assessment and data collection. Johnson and George 24 state, “The hypothesis should be based on the presenting information about the patient, the patient’s condition and available history, as well as the SLP’s extensive knowledge of the discipline.” They caution that “without a reasonable hypothesis to be tested in diagnostic activity, the clinician is likely to expend time in unnecessary testing” (p. 341).

Forming a hypothesis or differential diagnosis narrows the possibilities and leads to a focused and organized assessment. Once a hypothesis is formulated, the assessment is then designed to rule in or rule out the potential hypothesis, and the appropriate selection of test materials enables the clinician to identify the presenting problem (or problems), helps reach the most likely explanation for why the patient is experiencing a particular deficit, and assists in treatment planning and deciding on a likely prognosis. 25, 26 Further, the speech-language differential diagnosis can contribute to and inform the medical differential diagnosis. 6

Some examples of the potential differential diagnoses considered by SLPs in acute-care settings may include

Oropharyngeal vs. esophageal dysphagia

Acute vs. chronic vs. progressive disorder

Cognitive vs. linguistic deficit

Language vs. motor speech disorder

Behavior/motivation problem vs. cognitive impairment

Upper motor neuron vs. lower motor neuron disorders

Apraxia of speech vs. dysarthria

Functional (psychogenic) vs. neurogenic communication impairment

15.5.2 Case Study 1

The SLP received a consult request for assessment of swallowing in an 82-year-old retired priest with confirmed dementia, who resided in an assisted living facility (ALF) for clergy. The patient was admitted following the fourth fall of an unknown nature in the past several weeks. The medical record was limited, because the majority of his care had been at an outside facility. Head imaging revealed no new brain injury; however, the patient had multiple chronic lacunar infarcts, including in the bilateral basal ganglia and cerebellum. The consult request for speech-language pathology services stated, “Patient with dementia, coughing when drinking and can’t chew solids, please advise appropriate diet.” Following the chart review and an interview with the caregiver from the ALF, the SLP met the patient. During the patient interview, she noted slurred and imprecise speech consistent with an ataxic dysarthria. In the interview, the patient demonstrated good awareness, memory, and orientation, and he was able to provide a detailed account of his most recent fall that was consistent with the medical record. He also expressed concern that his recent falls occurred during the night when he woke up to go to the bathroom, and he stated that his difficulties began several months earlier when he suffered a stroke. The SLP, hypothesizing that the primary etiology was residual stroke impairments rather than dementia, completed a focused assessment to target oral-motor, speech, and swallowing function and that identified strategies and compensatory maneuvers to improve speech intelligibility and minimize aspiration. In conversation with the physical therapist, it was noted that the patient had poor balance and disrupted gait, which are also consistent with cerebellar dysfunction. After the above information was presented to the medical team, it was determined that the most likely cause for the frequent falls and speech and swallowing dysfunction was neurogenic. A neurology consult was generated to assist with stroke management and prevention, a geri-psychiatric consult was requested to assist with a more accurate determination of dementia, and the patient was referred to an inpatient rehab setting for speech, physical, and occupational therapy.

Patient Complexity and Risk Assumption

As a result of medical and technological advances, patients in acute-care settings are increasingly complex in their medical presentation. The care of patients is becoming more time and resource demanding, necessitating an increasing ability to integrate a broader amount of information into the care process. However, in its broadest sense, it is not just the number of medical conditions that increase the complexity of caring for a patient, but the interplay of multiple, coexisting conditions. 27 A patient with numerous, chronic, frequently encountered medical conditions (such as coronary artery disease, diabetes, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), deficient baseline cognitive status, limited financial means, and advanced age will require creative and thoughtful planning by the entire multidisciplinary team to achieve the best health outcomes. Likewise, the speech-language intervention must also consider a multitude of domains (medical, psychosocial, cognitive, ethical) and incorporate this knowledge into determining patient care needs. Specific considerations for the SLP in caring for a complex patient are listed in ▶ Table 15.5. 27, 28

Acute Care | Rehabilitation |

What is the problem? | What are the impairments and functional limitations? |

What is the cause? | What is the cause? |

What are the severity and prognosis? | What are the severity and anticipated course of recovery? |

Is patient’s behavior/communication/swallowing consistent with the medical condition? | Is patient’s behavior/communication/ swallowing consistent with the etiology? |

Is there any immediate medical/surgical intervention available to help the patient? | What treatment will be beneficial for these impairments? |

What speech-language-swallowing intervention is needed? | Is treatment helping? |

What additional follow-up will be needed? | If not, what changes to treatment are indicated? |

How can the results of this assessment contribute to overall patient care and safety? | How can the results of this assessment help plan for best functioning after discharge? |

Adapted from Johnson et al, 29 p. 339. | |

The concept of medical frailty as it relates to assumption of risk in decision making also deserves close consideration in the acute-care environment. Bortz 30 defines frailty as “a state of muscular weakness and other secondary widely distributed losses in function and structure that are usually initiated by decreased levels of physical activity” and notes that “acute events conspire in major ways to provoke frailty” (p. 284). Risk factors for provoking frailty include toxins, infections, injuries, and malignancy, all exacerbated by nutritional problems. Frailty, generally thought of in terms of the elderly, is considered a biologic syndrome characterized by diminished reserve and decreased resistance to stressors resulting from cumulative declines across multiple physiologic systems. 31 Specifically, diminished physical activity due to muscle weakness results in slowed performance, fatigue, poor endurance, and unintentional weight loss. 30 Frailty can occur in younger patients with severe deconditioning after critical illness. Frailty leads to reduced functional reserve and increased vulnerability. 32, 33 The medical SLP must consider the overall state of the patient and what complications might ensue should the patient aspirate, contract an infection, or receive insufficient nutrition. Frail patients do not have the reserve or capacity to fight off infection, are rarely ambulating to maintain endurance, may have a weak, ineffective cough with reduced airway protection should aspiration occur, and may be too easily fatigued to consume sufficient nutrients. Consideration of frailty, along with specific swallowing function impairments, will lead to more focused and appropriate management, with an emphasis on overall patient health status and safety. 32, 34

15.6 Targeted and Appropriate Assessments

The SLP in the acute-care setting tailors the assessment to identify the presence and severity of deficits systematically, to interpret their clinical significance, and to confirm or rule out likely diagnoses. ▶ Appendix 15.3 describes the main components of an SLP evaluation; however, these components will be tailored according to each specific patient’s needs. The assessment must answer the question asked by the consulting service relative to the presenting complaint. Because of time constraints and patient characteristics, the assessment may be limited to the issues that have the greatest impact on the patient’s medical stability and on the discharge decision making process for the patient, family, or team (Table 15–6).

Multiple chronic conditions = | increased risk of pneumonia increased likelihood of multiple medications increased likelihood of reduced ambulation |

Poor mental status = | inability to maintain arousal during a meal inability to recall safe swallowing strategies inability to attend to treatment activity |

Limited financial means= | limited rehabilitation options reduced finances for medications and treatment |

Limited family/social supports= | unsafe living environment lack of assistance at home for daily living activities inability to drive to outpatient treatment, medical appointments, and for personal needs |

Advanced age= | increased fragility increased comorbidities |

The clinician must be a keen and sensitive observer, meticulously recording all behaviors, gross and subtle, as the patient may tolerate only a brief encounter. The process of data collection and symptom monitoring must be efficient to generate an appropriate diagnosis. Repeated short visits may be more appropriate than a single long evaluation session. Formal testing can provide the clinician, particularly one with less experience, with a hierarchical framework to evaluate a particular function. With experience, astute observational skills, and intuition, clinicians can modify formal testing to facilitate extrapolation of information. During the initial assessment, the clinician should be prepared for discovering unanticipated speech, language, and/or swallowing findings, which may necessitate a rapid adjustment in the exam to match the patient’s needs, to best elicit and define abnormal behaviors, and to add to an alternative hypothesis. Furthermore, given the rapidly changing acute-care patient, the patient may be too lethargic, too medicated, or too ill to complete the assessment in one session or to complete all facets of the exam. Alternatively, the SLP may vie for time with competing tests, procedures, and other medical consultants.

15.6.1 Case Study 2

Ms. T, a 62-year-old female, was admitted to the general medicine service with increasing weight loss and dehydration. Her work-up by the medical team revealed progressive speech changes, upper extremity weakness, including mild loss of fine motor dexterity in her hands, and shortness of breath without a known cause. The oral-motor speech evaluation yielded diagnostic clues, including fasciculations of the chin and tongue, hyperreflexia (jaw jerk, suck and snout reflex), and mixed flaccid-spastic dysarthria. The SLP strongly suspected that the constellation of these upper and lower motor neuron findings pointed to a motor neuron disorder and warranted neurology consultation. To accommodate the patient’s fatigue and difficulty chewing, the patient’s diet was modified to a soft diet and a nutrition consultation was advised to assist with strategies to maximize nutrition and hydration. Although the diagnosis of ALS was strongly suspected, the medical team determined that until the diagnosis was confirmed, long-term-care issues, such as placement of a feeding tube, determination of patient wishes regarding life- sustaining measures, and alternative communication methods, should be deferred to care in the outpatient setting.

15.7 Cognitive-Communicative Assessment in Acute Care

Although the evaluation of a patient’s swallowing ability and the need to determine a safe mode of nutrition may typically constitute the primary reason for referral, the SLP should not fail to address all parameters that fall within the SLP domain, including language, cognition, communication, and speech. The importance of addressing the patient’s communication abilities should not be overlooked. The SLP advocates for communication needs, provides patients and families with education and support, and provides valuable information about the patient’s cognitive-communicative status to the health care team. 35 Often, changes in speech, language, or cognition may be the initial presenting symptoms of an underlying neurologic condition and the SLP assessment may be critical to guiding the diagnostic process. 26

Both standardized and nonstandardized assessments may be utilized depending on the purpose of the assessment and the patient’s ability to participate. In general, formal treatment planning does not occur during the acute hospital stay, so the diagnostic process needs to be focused and individualized to the patient’s needs. 36 Key questions may include the following: Does the patient have a problem? If there is a cognitive-communicative disorder, what are its characteristics? What are the implications of the test results beyond the test session? 37

Furthermore, the realities of acute care today demand cognitive-linguistic testing that is not only well designed, but sensitive, standardized, and quantifiable, yet brief. 13, 38 Several excellent evidence-based reviews and recommendations include

ASHA’s Compendium of EBP Guidelines and Systematic Reviews http://www.asha.org/members/ebp/compendium/

ANCDS (Academy of Neurologic Communication Disorders and Sciences) Practice Guidelines and Practice Resources http://www.ancds.org/

COMBI (The Center for Outcome Measurement in Brain Injury) http://www.tbims.org/combi/

Practice Guidelines for Standardized Assessment for Persons with TBI. ANCDS Bulletin Board/Vol. 13, No. 2

Several tools that are both well designed and tested, as well as useful for neurocognitive assessment and/or monitoring in the acute-care setting, can be found in ▶ Table 15.7. This is not an exhaustive listing, however. The SLP also should be mindful that a brief cognitive screening may not be sensitive enough to detect higher-level executive function impairments. It may be useful to pair a brief cognitive screening with a structured interview and informal executive function tasks. And, as always, the SLP must synthesize the patient’s information, including age, community needs, baseline functioning, family support, neuroimaging findings, loss of consciousness, etc., to better determine risk factors and to formulate a focused plan. Referral for a follow-up outpatient neuropsychological and/or SLP cognitive-communicative assessment after discharge may be useful too, for patients with impairments.

Behavioral scales |

|

Cognitive measurement tools |

|

Language measurements |

|

Functional communication measures |

|

15.8 Swallowing Assessment in Acute Care

The purpose of the clinical swallowing examination in acute care is to determine the patient’s safety and efficiency for oral intake. The concepts of safety and efficiency take on a unique significance in the context of acute hospitalization. Whereas in the outpatient setting recurrent or persistent aspiration may be tolerated by the patient to the extent that oral intake may be feasible, in the acute-care context, hospital-acquired pneumonia, such as aspiration pneumonia, may be extremely detrimental to the overall outcome and therefore its prevention is crucial. At the same time, nonoral nutrition carries its own risks of complications, such as sinusitis from the long-term presence of a nasogastric feeding tube, dislodgement of the feeding tube, intolerance to tube-feed formula, and increased oral colonization in a patient who is NPO. Thus, the SLP performs a delicate balancing act between maintaining NPO status and initiation of an oral diet, ensuring team collaboration when making nutritional recommendations for a patient in the acute-care situation. Depending on the diagnosis and because of the effect that aspiration can have on the patient’s hospitalization and overall outcome, it is the clinician’s responsibility to “disprove” aspiration, as well as to prove safe swallowing. Furthermore, the acute-care SLP must always be vigilant in considering the reliability of the data collected in any one diagnostic session to predict overall function. If it is only possible to evaluate the patient with a few bites or sips before needing to stop because of patient response, data collection may be inadequate and further evaluation at a later date may be required. Representative sampling, a construct open to interpretation, is needed to predict behavior under regular circumstances, when fatigue, distraction, pain, and attention deficits may interfere with swallowing safety and efficiency.

15.9 The Role of Instrumental Evaluation in Acute Care

It is well known that the clinical bedside evaluation has significant limitations with respect to validity and reliability, . 39, 40 Since understanding the physiology of the swallow in addition to other patient variables is critical for making recommendations for safe oral nutrition, many patients in the acute-care situation may be candidates for an instrumental evaluation. Choosing the type of instrumental exam and the timing of the exam may depend directly on the question at hand, taking into consideration the type of instrumental test available, patient factors like hemodynamic and medical stability, the patient’s ability to follow directions and to complete strategies, the patient’s overall level of debilitation, and scheduling constraints in the facility.

Some acute-care hospital environments only have access to VFSS. Where laryngoscopic evaluation of swallowing is possible, selection of fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES) over VFSS relates to the question being asked and the patient’s status. A patient in intensive care may not be sufficiently stable to travel to the radiology suite for VFSS, or positioning or body habitus (patient’s physical condition) may preclude a radiologic assessment. However, if an esophageal disorder is suspected, the patient may not be appropriate for FEES. Direct visualization of laryngeal function is appropriate if the question relates to secretion management or vocal fold function or another structural abnormality. In experienced hands, FEES can provide essential information about the physiology of the swallow and can demonstrate the impact of therapeutic strategies. Sometimes more than one procedure is required. A FEES study may be performed as a preliminary investigation in the knowledge that VFSS may be necessary when the patient can safely to travel the radiology suite. The expertise of the clinician in performing the instrumental examination will also contribute to the data that are derived. Descriptions of VFSS and FEES can be found in Chapter 10 and Chapter 11 of this text, respectively.

Precautions should be taken in performing instrumental examinations in the acute-care setting, and, in light of a patient’s fluctuating medical status, it is important to update status immediately prior to conducting the examination. Patients may be restricted with respect to positioning. The SLP should inquire about the patient’s need for hemodynamic monitoring with cardiac telemetry or for oxygen saturation. In such situations, a nurse or respiratory therapist may need to accompany the patient to the radiology suite for the examination.

Specific precautions to be communicated to the radiology staff regarding the patient include positioning constraints and infection precautions (such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus [MRSA]) so as to protect both the staff and the patient. Endotracheal suctioning equipment should be set up in preparation for the patient who has a tracheostomy tube or who has difficulty managing secretions. Following the swallow study, the patient should be carefully positioned and should be monitored closely while awaiting transport back to the hospital unit to ensure safe transfer.

With respect to FEES, similar precautions are necessary. Clinicians should check with the referring service regarding the patient’s coagulation status, because introduction of the endoscope can cause bleeding. Patients with facial fractures, hemodynamic instability likely to promote vasovagal events, or recent administration of tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) or those on noninvasive ventilation may not be candidates for FEES exams.

15.9.1 Synthesis of Test Findings with Patient Factors to Make an Informed Clinical Judgment

The SLP synthesizes the specific findings on the exam and the nature of the disorder with the patient’s medical diagnosis, medical care plan, and anticipated outcome in order to make appropriate clinical decisions and to recommend treatment. 41 Description of etiology, differential diagnosis, a focused treatment plan with a clear rationale, and a prognostic statement are the hallmarks of powerful clinical communications. Murray 42 states, “The clinician should describe in exact terms the potential for poor outcome should treatment not be provided. Recommendations should directly respond to the consulting physician’s interest in requesting the consult.” Both immediate and long-term needs of the patient should be addressed.

Case Study 3

Ms. G, an 81-year-old female, was relatively healthy until 6 months earlier, when she began to decline functionally, to experience changes in her swallowing ability, and to lose weight. She was admitted to the hospital with pneumonia, rapidly developed pulmonary and cardiac complications, and suffered a small left hemispheric stroke. She received tPA in the hospital and the majority of her acute stroke symptoms resolved.

During the SLP interview, the patient confirmed gradually worsening swallow function over the prior 6 months, including a sensation of hard food items and pills sticking in her throat, intermittent immediate regurgitation, coughing when drinking large sips of liquid, and increased time needed to eat. The dysphagia assessment, including a VFSS, showed a moderate-size Zenker’s diverticulum in addition to base of tongue retraction and bilateral pharyngeal weakness. These impairments resulted in reduced bolus drive, causing a significant pharyngeal residue that necessitated multiple swallows per bolus. The residue resulted in mild persistent aspiration on liquids after the swallow and elicited a weak, ineffective cough.

Integrating the findings of the clinical and instrumental examinations gave the impression of acute dysphagia imposed on chronic dysphagia. The patient’s swallowing dysfunction predated and likely precipitated the admitting aspiration pneumonia and was exacerbated by the acute cerebrovascular event. The underlying problem rendered the patient fragile and easily fatigued. Although compensatory therapeutic swallowing strategies, including head rotation, multiple swallows, and liquid rinse, all assisted in clearing the pharyngeal residue, the energy expenditure required to complete these strategies for oral nutrition at a meal was determined to be too significant. Neither the gastroenterologist nor the SLP judge the diverticulum to warrant repair, given the patient’s medical fragility. The SLP recommended nonoral alternate hydration and nutrition as a bridge during the rehabilitation phase, as well as small amounts of oral intake for comfort using the prescribed compensatory strategies. The SLP predicted that once the patient’s medical course stabilized, inpatient rehabilitation would focus on maximizing her ambulation, overall endurance, nutritional status, and swallowing function, allowing her to resume oral nutrition and to return home with her family.

Communication of Findings to Health Care Team, Patient, and Family

Communicating the findings of the evaluation to the health care team in an effective and efficient manner is challenging, yet is critically important in the acute-care setting. Updating status changes and recommendations throughout the hospitalization is further challenged by the abundance of chart notes, reports, and other consultations that fill the patient’s medical record. Murray 40 notes that “the value of even the most effective and artfully applied assessment is reduced without skillful, concise, and accurate communication of our activities.” Many providers in rotating teams interact daily with patients in large, fast-paced tertiary care or academic medical centers. Medical residents work in a team, so that each day a different resident may be the primary contact person. Nurses change their shifts and are not necessarily assigned to the same patients on consecutive days. Hospitalists, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants may also work varied and intermittent shifts, with frequent hand-offs to one another each day. Family members may visit after the workday has ended or on weekends. Furthermore, patient care rounds may or may not take place daily, and the SLP may or may not be available to attend. Given these challenges, the following are several key guidelines:

Communication needs to take place on a continuous basis.

Information should be presented in varied formats, e.g., the EMR, paging, phone calls, oral report to team members, team meetings.

Findings, recommendations, and changes to the patient’s status along the way need to be made in a timely manner, and need to be be concise, but must also convey the SLP’s thought process and opinion.

Communication should involve all members of the health care team as needed (nurse, PT, case manager, dietician, etc.), as well as the patient and the primary caregivers.

Information should be presented in a manner that is sensitive to the patient’s or family’s emotional state and considers the sense of crisis that they may be experiencing.

Experts in counseling and end-of-life issues, such as social workers and palliative care consultants, should be utilized to assist with difficult discussions.

Written Documentation

Because of the essential nature of the written report, and its importance in communicating the clinical work performed, documentation needs to be thorough and effective, yet concise and succinct. The quality of the written report will help to establish the quality of the SLP service and can make a lasting impression on the reader. 40

Documentation primarily serves to record the clinical history, problems, and course of care; to communicate with other practitioners; to document services for quality assurance and reimbursement purposes; and to act as legal evidence in a court of law. 43 The documented information becomes part of the permanent and legal medical record and supports patient billing. Documentation is completed and placed in the medical record immediately after the patient encounter.

Written documentation in the acute setting generally includes:

Diagnostic reports

Progress notes

Discharge summaries

Letters/email to the patient and/or other providers

The format and process of documentation vary greatly from facility to facility, although regulatory bodies, such as the Joint Commission, dictate minimal standards. Each institution will have its own documentation conventions. These can include checklists and narrative, and often some combination of the two. Regardless of the style, the consult report and subsequent progress notes are composed of several key, standard sections ( ▶ Table 15.8).

Evaluation Report | Progress Note | Section Description/Contents |

Introductory Statement History of Present Illness Previous Medical and Surgical History | Subjective | Patient history, complaints, current status/presentation, reason for consultation or visit |

Examination | Objective | Objective clinical data: exam parameters, tests given, measurements, diagnostic observations without interpretation |

Impressions | Assessment | Diagnosis/current state of the swallowing, communication, or cognitive deficit; integration of all the objective data with SLP interpretation; changes from previous sessions; proposed interventions and patient response; severity and prognosis |

Recommendations/Plan | Plan | Recommendations to the consulting MD regarding patient management; direct response to the consult question; plans/rationale for ongoing intervention; additional referrals recommended; discharge plan/status and need for SLP services |

Patient/Family Education | Patient/family education | Describes information provided; reviews findings and recommendations; indicates patient’s/family’s level of understanding, barriers to education, and ways to overcome them |

SLP = speech-language pathologist | ||

The development and implementation of the electronic medical record (EMR) have surged over the last several years with health care reform changes and in an effort to promote a safer and more cost-effective health care system, although many hospitals are still struggling to adapt to the changes. 44, 45 Each documentation format has benefits and limitations, but the principles of documentation will determine the most appropriate format for a particular institution ( ▶ Table 15.9).

Reflects careful observation, examination, and testing of swallowing, communication, and cognition. |

Defines patient’s status with clear and specific measures. |

Forms the basis for planning care, drives and defines the treatment plan, and supports SLP impressions and recommendations. |

Presents the reader with evidence and rationale for why SLP services are needed. |

Serves as the primary form of communication between care providers. |

Assists the clinician to self-reflect, integrate information, and pull the story together; reflects the clinician’s thought process. |

Provides the patient with education and information about what was found and what is recommended. |

Meets regulatory agency and institution requirements. |

Supports billing. |

Protects legal interests of patient, hospital, and clinician. |

SLP = speech-language pathologist |

Re-assessment and Monitoring of Patient’s Status in a Dynamic Clinical Setting

Ongoing SLP monitoring and intervention continue after the assessment is completed and is essential in reducing re-admissions, improving patient health outcomes, and expediting an appropriate discharge plan. The SLP may be the health care provider who identifies a decline in the patient cognitive-communicative status that may indicate a new infection or bleed, or may collaborate with the medical team to identify the effectiveness of a medical intervention by tracking improvements, 46 such as improvements in dysarthria and dysphagia in a patient with myasthenia gravis following a new dosage of Mestinon. Dynamic changes in patient condition demand reassessment and potential changes in recommendations. The frequency of follow-up and the length of treatment sessions following an initial assessment are driven by each patient’s clinical condition and treatment needs. Although diagnostic evaluation activities and observation encompass the bulk of the work in acute care, often this work is done over the course of multiple treatment sessions in order to provide the clinician with further information that supports or disputes the initial impressions and findings. A variety of patient-care situations may require follow-up monitoring and/or intervention, such as

Decline in medical status: A patient with a frail/critical clinical condition who requires close monitoring of diet tolerance, such as a recently extubated patient with higher oxygen needs who is started on an oral diet that may need to be discontinued if there is any negative effect on the patient’s respiratory or medical status

Improvement in medical status: A patient with an acute medical status that is anticipated to improve and stabilize rapidly, such as an acute stroke patient who is seen on the first day after a stroke and is not yet deemed safe for oral intake, yet is expected to stabilize in the next several days, which may allow for initiation of an oral diet

SLP intervention is integral to affecting a change in status: For a patient in the midst of a tracheostomy tube downsize/decannulation process, the SLP involvement is essential for speaking valve use; or a patient may need further education and training to independently complete a swallowing strategy or modification that will allow an upgrade to a less-restrictive diet

Further testing: A patient with a clinical need for instrumental examination following the clinical swallow evaluation to better understand the swallow mechanism, to assess for aspiration, and to determine safest diet consistency and strategies

Neuro-cognitive monitoring: A patient with cognitive-linguistic impairments who needs ongoing monitoring of deficits, monitoring to track recovery, as well as evaluation for predicting rehab prognosis, identifying rehab goals, determining an appropriate rehab setting, and providing family support/patient education

Quality-of-life/end-of-life issues: A patient requiring assistance in communicating his or her wishes, collaborating with the social worker to complete a health care proxy, and providing education to the medical team regarding the impact of aphasia on decision-making capacity

SLPs must be cognizant of the importance of following their patients after completing initial evaluations when warranted, especially as it relates to their integral role in reducing re-admissions, improving patient health, and expediting an appropriate discharge plan.

Advocacy, Patient Management, and Education