Pneumoconioses

Pneumoconioses are changes in the lung parenchyma in response to inhalation of inorganic dusts. The type and severity of parenchymal reaction to an inhaled dust depends on the type of dust, the amount and circumstances of the exposure, and individual susceptibility. Most inorganic dust exposures producing pneumoconioses are occupational exposures.

Part 1 Asbestosis

Alvaro C. Laga

Timothy C. Allen

Philip T. Cagle

Asbestosis is defined as a specific type of diffuse bilateral interstitial pulmonary fibrosis caused by inhalation of large numbers of asbestos fibers. Asbestosis is a disease that has a dose-response relationship and is dependent on host susceptibility; therefore, a certain amount of asbestos exposure is required before there is a risk of developing asbestosis, and not everyone exposed to the same level of asbestos will develop the disease. In a cohort of sufficiently exposed individuals, the risk of asbestosis increases as the amount of exposure increases above the threshold. Asbestosis has a latency of decades, averaging 20 to 40 years but sometimes longer, after first exposure before it is manifest. Because it is a long chronic disease, the fibrosis seen in asbestosis is primarily mature collagen rather than granulation tissue such as that seen in acute lung injuries.

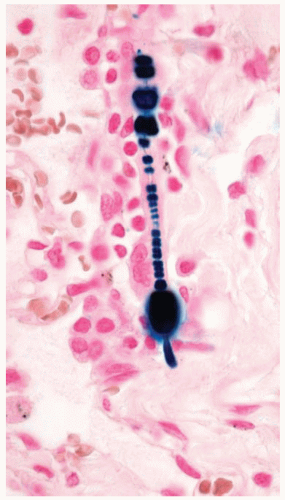

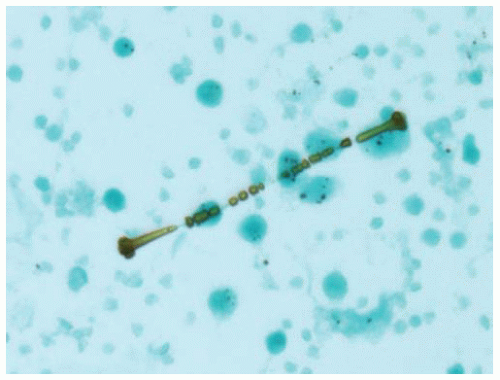

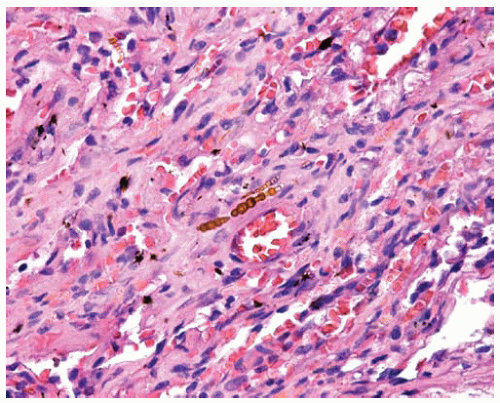

Asbestos is a fibrous silicate that has had multiple uses, especially as a fire retardant and insulator. Asbestos fibers are divided into two broad categories: serpentine type (chrysotile) and amphibole (amosite, crocidolite, and others). Asbestos fibers are clear, but a percentage of inhaled fibers are coated with iron and protein creating an asbestos body. Asbestos bodies can be seen as beaded barbell-shaped structures with a clear fiber core on routine cytology and histology sections (Papanicolaou and hematoxylin and eosin stains), with iron showing a golden brown color. Iron stains highlight the iron coatings of asbestos bodies as bright blue against a pale pink background, making them stand out and easier to identify. Asbestos bodies are one type of ferruginous or iron-coated bodies that may be seen in the lung. Other types of fibers and particles, when coated by iron, are also ferruginous bodies and should be distinguished from asbestos bodies. The number of asbestos bodies roughly corresponds to the number of asbestos fibers and can be used to gauge the amount of asbestos exposure an individual has received. A count of asbestos bodies by light microscopy or asbestos fibers by electron microscopy can be performed after digestion of a known weight of lung tissue to give a concentration in the person’s lung tissue.

It is important to distinguish between history of exposure to asbestos and asbestosis. By themselves, asbestos bodies or asbestos fibers indicate exposure but do not indicate whether a person has the disease asbestosis, which requires evaluation of the lung tissue for characteristic fibrosis in addition to asbestos exposure. Asbestos bodies may be observed in lung tissue of occupationally exposed individuals who do not have any resulting fibrosis. Studies have also shown that virtually all individuals in the general population who have not had occupational exposure have asbestos fibers and bodies in their lungs that they have inhaled from the background levels of asbestos present in the ambient air, primarily in urban environments. Therefore, it is possible to observe asbestos bodies in any person in the general population who has not had occupational or bystander exposure to asbestos, but if observed, these bodies would not be in quantities sufficient to produce asbestosis. In actual practice, it is uncommon to come across asbestos bodies in routine tissue sections or cytology specimens from persons without some exposure to asbestos above background levels.

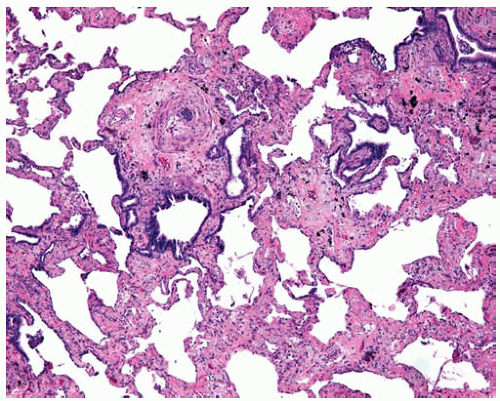

Asbestosis is a specific type of fibrosis related to asbestos exposure and begins in the first tiers of alveolar septa in respiratory bronchioles (see Chapter 67). Asbestosis may progress and the amount of interstitial fibrosis increase until there is end-stage honeycomb lung. The radiologic and gross distribution of asbestosis mimics that of usual interstitial pneumonia in that it is worse in the lower lung zones and periphery. Therefore, the clinical and radiologic presentation of asbestosis may mimic other interstitial lung diseases and vice versa. Gross examination of lungs from autopsies of patients with asbestosis reveals fibrosis and honeycombing that is more severe in the lower zones and peripheral lung parenchyma.

Although asbestosis may be accompanied by pleural changes, including pleural plaques and pleural thickening, these pleural changes can also be present without parenchymal fibrosis; therefore, they should not be called asbestosis. The term asbestosis should be reserved only for the parenchymal disease.

Cytologic Features

Asbestos fibers may be found in sputum and lavage specimens of persons with asbestos exposure, with or without asbestosis (asbestosis cannot be diagnosed from cytology specimens).

The asbestos fiber is clear on Papanicolaou stain, but its iron-containing proteinaceous coat stains golden yellow to brown.

Occasionally asbestos bodies may be partially encased by macrophages.

Histologic Features

Diagnosis of asbestosis requires (i) a characteristic pattern of diffuse interstitial fibrosis, as discussed later; and (ii) the presence of asbestos bodies, as discussed later.

Interstitial fibrosis in asbestosis consists of mature collagen from the chronic course of the disease; young fibrosis consisting of granulation tissue (such as that seen with organizing pneumonia or organizing diffuse alveolar damage) is not asbestosis.

Interstitial fibrosis of asbestosis generally begins around the respiratory bronchioles where the earliest or minimal changes is fibrosis of the first tier(s) of alveolar septa of the respiratory bronchioles; this should be distinguished from respiratory bronchiolitis caused by smoking or other etiologies.

Fibrosis of asbestosis may progress to involve more alveolar septa between bronchioles and eventually progress to end-stage honeycomb lung.

The severity of asbestosis is worse in the lower lung zones and at the peripheries; fibrosis that is worse in the upper lung zones, focal, or not bilateral does not fulfill criteria of asbestosis.

Limited biopsies such as transbronchial biopsies or needle biopsies do not permit evaluation of enough lung tissue to exclude or confirm a diagnosis of asbestosis; peribronchiolar fibrosis may not be sampled and focal scars cannot be ruled out; a wedge biopsy is required as a minimum to evaluate for asbestosis.

In addition to a characteristic pattern of fibrosis, a minimum of two asbestos bodies is required to diagnose asbestosis (this rule is used to eliminate the chance of occasionally finding an asbestos body in persons without sufficient asbestos exposure as the cause of any observed fibrosis); generally, as the observed severity of the fibrosis of asbestosis increases, the number of asbestos bodies observed in the tissue sections increases.

There may be ancillary changes associated with asbestosis, such as multinucleated giant cells (which may contain asbestos bodies), presence of blue bodies, pseudodesquamative interstitial pneumonia reaction to the fibrosis and superimposed infections, tobacco-related changes, or mixed dust pneumoconioses; confirmation or exclusion of asbestosis requires careful evaluation of at least a wedge biopsy of lung tissue.

Asbestos bodies, by themselves, are only markers of asbestos exposure and do not represent the interstitial lung disease asbestosis unless the characteristic interstitial fibrosis is also present.

Pleural plaques due to asbestos exposure by themselves are only markers of asbestos exposure and do not represent the interstitial lung disease asbestosis; unlike asbestos bodies, pleural plaques are not required for a diagnosis of asbestosis.

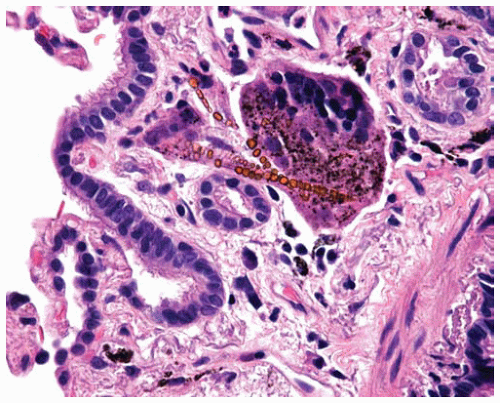

Figure 85.1 Papanicolaou stain of a bronchoalveolar lavage shows an asbestos body with a clear fibrous core coated with golden brown iron forming a barbell-shaped structure. |

Figure 85.2 Gross lung figure from autopsy of patient with severe asbestosis shows peripheral fibrosis and end-stage honeycomb lung in the lower zones. |

Figure 85.4 Interstitial scarring of asbestosis with asbestos bodies in the mature collagen. They are composed of clear cores coated with refractile golden brown beads of iron. |

Figure 85.5 Submucosal multinucleated giant cell partially engulfing asbestos bodies with clear cores coated with refractile golden brown beads of iron. |

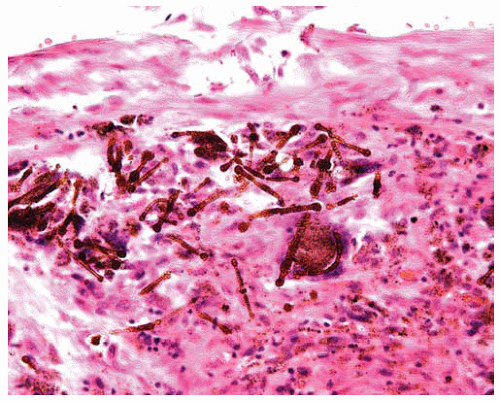

Figure 85.6 Large numbers of golden brown barbell-shaped asbestos bodies are within a large interstitial scar of severe asbestosis. |

Part 2 Silicosis

Alvaro C. Laga

Timothy C. Allen

Keith M. Kerr

Philip T. Cagle

Silicosis is the pulmonary disease that results from exposure to large amounts of crystalline silica (quartz). High levels of silica exposure potentially occur in coal and other miners, sandblasters, glass manufacturers, quarry workers, and stone dressers. The lesions found in silicosis are referred to as silicotic nodules.

The classic nodular or chronic silicosis has a latency period averaging 20 to 40 years after initial exposure. Development and progression of silicosis may occur after cessation of exposure to silica. Rarely, accelerated silicosis may develop in 3 to 10 years. Acute silicosis is the result of a massive, overwhelming exposure and produces a pulmonary alveolar proteinosis (see Chapter 76).

In contrast to asbestosis, silicosis is more severe in the upper lung zones. The number and extent of silicotic nodules that can be observed range widely. Silicotic nodules may be found in the hilar lymph nodes without involvement of lung parenchyma, and this should not be called silicosis. It is not unusual to find an occasional small, clinically irrelevant silicotic nodule as an incidental finding in lung specimens. The presence of multiple silicotic nodules smaller than 1 cm in size is called simple silicosis. A minority of patients with simple silicosis progress to complicated silicosis or progressive massive fibrosis (PMF). PMF consists of silicotic nodules measuring greater than 1 cm in diameter, and there is confluence of silicotic nodules involving large areas of lung parenchyma. These large conglomerates of silicotic nodules may be cavitated. Patients with PMF may die of respiratory failure. In accelerated silicosis the silicotic nodules tend to be less well formed, and there is more accompanying interstitial fibrosis.

Grossly, the nodules are whorled, round, well-circumscribed, hard, slate gray, and sometimes calcified. Grossly, the pleural nodules have been referred to as candle-wax lesions or pleural pearls and consist of gray waxy nodules with an anthracotic rim. These are found more often on the visceral pleura than the parietal pleura.

Silica creates nodules in a lymphangitic distribution, including along the bronchovascular bundles, interlobular septa, and pleura, but nodules can be seen elsewhere in the lung parenchyma. Bronchial and hilar lymph nodes also often have similar nodules. Early nodules begin as collections of dust-laden macrophages typically containing anthracotic pigment mixed with minimal reticulin and collagen fibers. Gradually, the center of the nodule becomes increasingly more collagenized and fibrotic but retains the surrounding rim of dust-laden macrophages. Eventually, the nodule matures into a round to oval nodule composed primarily of whorls of hyalinized collagen with a peripheral rim of dust-laden macrophages. There may be so-called focal emphysema surrounding the silicotic nodule with fragmentation of the lung parenchyma adjacent to the fibrotic nodule.

In polarized light, silica particles are tiny 2-μm crystals that are typically only weakly birefringent. The silica particles are less conspicuous than the larger and more brightly birefringent silicate particles that often accompany them in the inhaled dust. It is important to distinguish silica particles as well from endogenous calcium oxalate crystals, “dirt” on the slide, or other endogenous or incidental particles that may be birefringent in polarized light (see Chapters 7, 8 and 9). In addition, tobacco smokers may have small collections of macrophages containing anthracotic pigment and birefringent particles that are a result of tobacco smoke and do not represent silicosis.

Patients with silicosis have an increased susceptibility to infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis, atypical mycobacteria, and fungus. Laboratory findings in simple silicosis include increased sedimentation rate, antinuclear antibodies, and immune complexes. Scleroderma has been found to be prevalent in silicotics.

Histologic Features

Early silicotic nodules consist of aggregates of dust-laden macrophages containing anthracotic pigment mixed with minimal reticulin and collagen fibers.

With progression, collagen begins to accumulate centrally within the nodule.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree